After two weeks of tense negotiations at COP26 in Scotland, the world has a new international climate change agreement: the Glasgow Climate Pact.

The new document does not replace the landmark Paris Agreement, but rather bolsters it with increased clarity on key issues. One of the major stakes going into this year’s COP was a matter of degrees. The world is teetering on the edge of keeping alive the possibility of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. Surpassing that threshold would be a death sentence for small island states and other vulnerable countries, and it all comes down to just how drastically nations are willing to cut their emissions. The pact gives added weight to the 1.5 degrees goal, and demands that countries do more to achieve it.

It also calls on rich countries to increase their financial support to help poorer nations adapt to rising seas and extreme weather, another priority for the meeting. And for the first time ever at a COP, the final text references “coal” and “fossil fuels” — the leading causes of climate change that were formerly taboo on the international stage.

But reactions to the agreement from many climate advocates and experts were tepid at best. “It’s meek, it’s weak, and the 1.5 degrees C goal is only just alive,” Greenpeace International executive director Jennifer Morgan said in a statement. “But a signal has been sent that the era of coal is ending. And that matters.”

Below, we take a look at the three major gaps in international progress on climate change going into COP26, and where they stand now.

1. The Emissions Gap

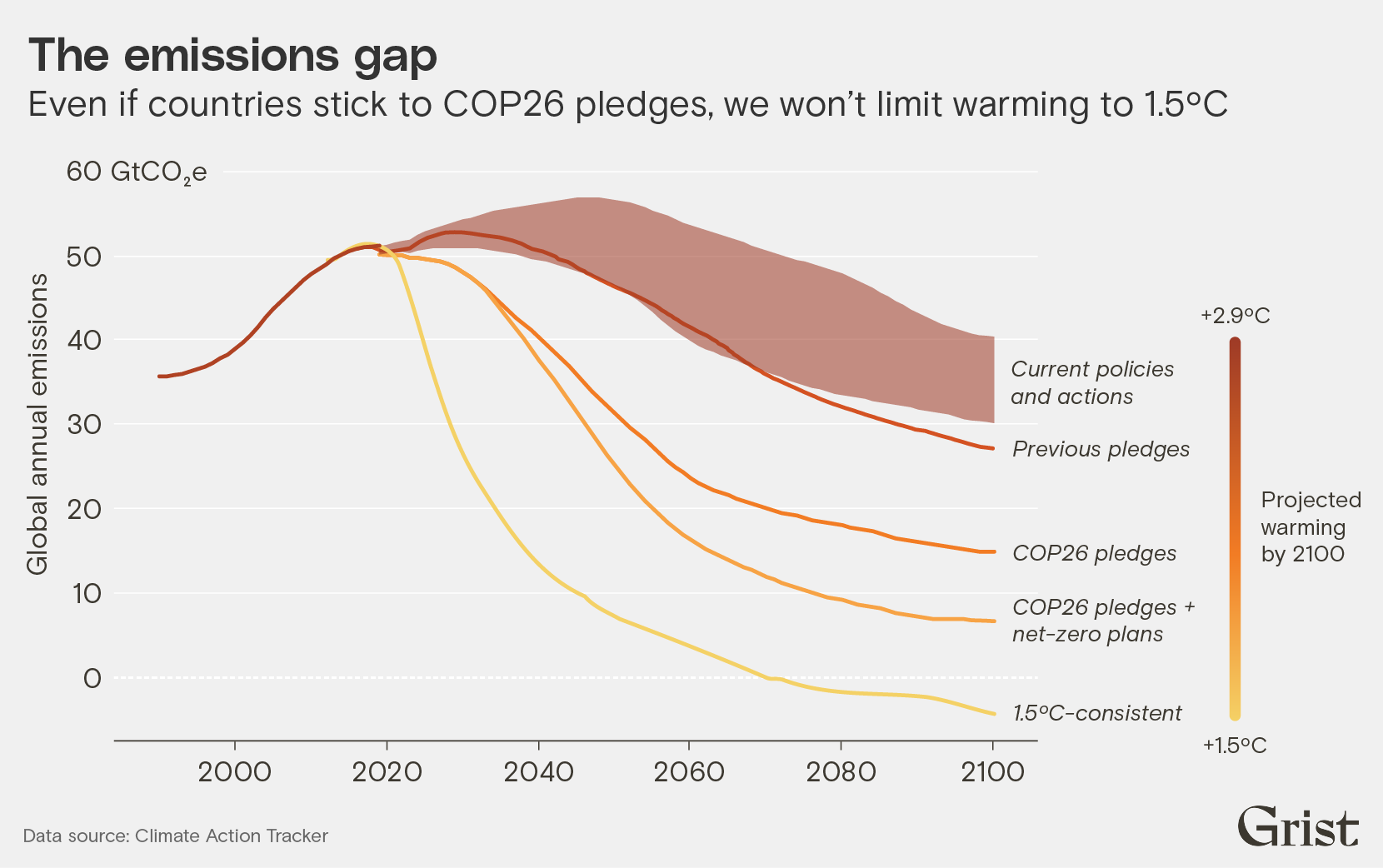

Before COP26, a United Nations analysis found that the world was not on track to achieve the Paris Agreement goal of limiting global warming to “well below” 2 degrees C, let alone the much safer goal of 1.5 degrees C. If countries met their 2030 emissions targets set prior to the start of the conference, the planet would still warm 2.7 degrees C by the end of the century.

After COP26, more countries have pledged steeper emissions cuts, but there is still a major gap in ambition between those pledges and what it would take to limit warming to 1.5 degrees C. Climate Action Tracker, a climate analysis firm, analyzed all of the official plans that countries submitted to the U.N. and found that if targets for 2030 were achieved, the world would still likely heat up by about 2.4 degrees C. The group also mapped out what it called an “optimistic” scenario, taking into account the less-official statements made by some countries that they will achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. In that case, the researchers found that the planet would warm by 1.8 degrees C.

Several other announcements made at the conference could improve the picture a bit more: More than 100 countries signed pledges to end deforestation and to cut methane emissions 30 percent by 2030. A few dozen countries pledged to phase out coal-fired power plants, though their timelines vary. Twenty-four countries and several major automakers agreed to sell only zero-emission vehicles by 2040.

In the end, the Glasgow Pact officially recognized that global carbon emissions have to be reduced by at least 45 percent by 2030 to limit warming to 1.5 degrees, and encouraged countries whose plans fell short of that target to submit new proposals by the end of next year. That’s a step forward, since otherwise countries would not be required to revisit their climate plans until 2025.

Perhaps the biggest question, post-COP26, is whether countries will follow through on the implementation of these pledges and plans. The U.S., for example, has a 1.5 degrees-aligned plan to cut emissions in half by 2030, but does not yet have policies in place that would allow it to achieve this.

2. The Fossil Fuel Production Gap

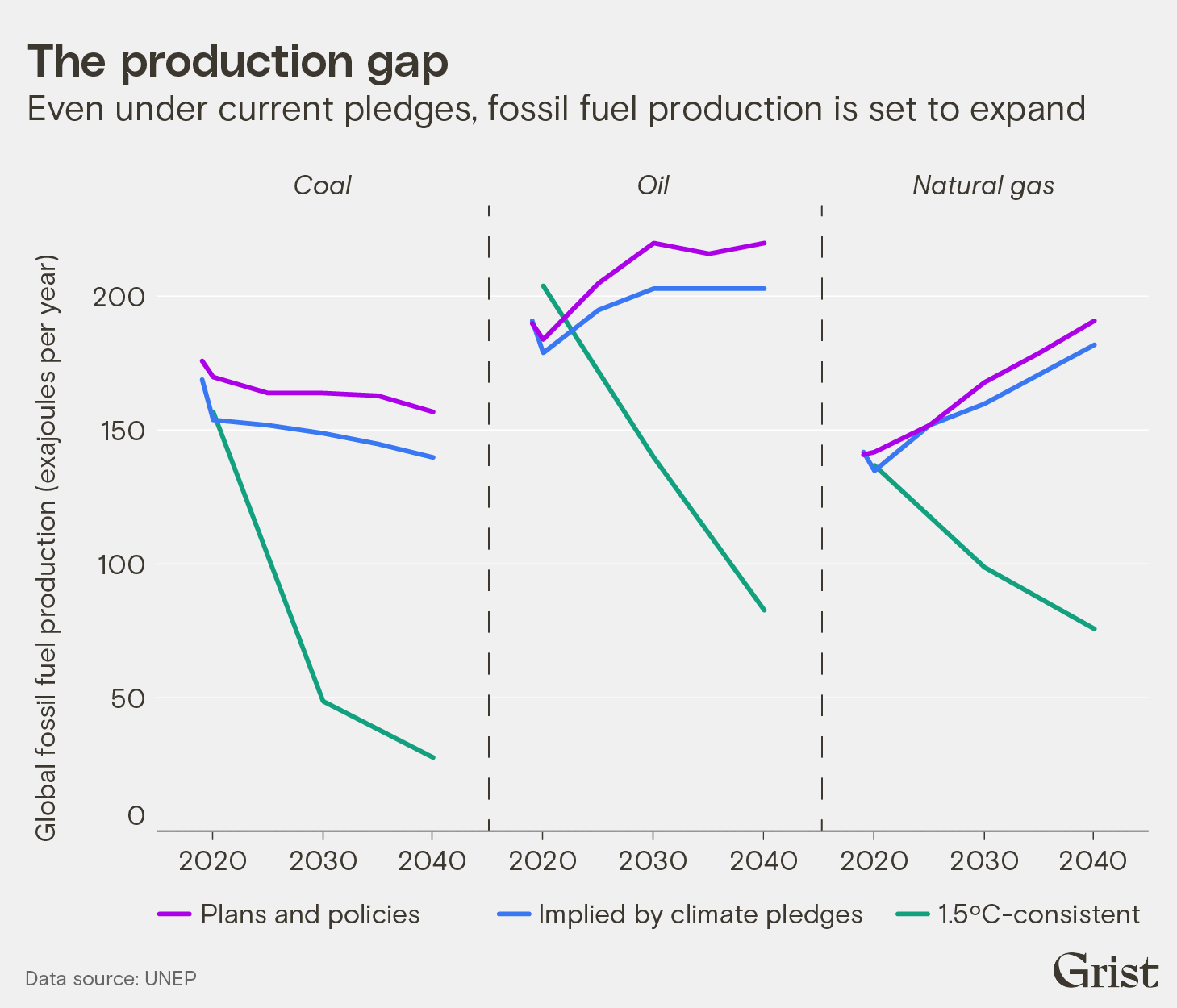

Before COP26, it was taboo to talk about fossil fuels at U.N. climate summits. The phrase “fossil fuel” never made it into the final text of a conference agreement. Negotiators talked about cutting emissions, sure, but largely avoided the sources of energy that are the leading cause of those emissions.

This avoidance allowed a world of demand-side policies to expand renewable energy, electric cars, and other clean technologies. But that hasn’t translated into a drop in supply. Oil and gas companies have plans to keep digging for the foreseeable future. Prior to COP26, a United Nations report that analyzed fossil fuel production plans of major economies warned that the world was on track to produce roughly 110 percent more coal, oil, and gas in 2030 than would be consistent with limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees C.

After COP26, the walls around the “F” words have started to crumble. During the conference, three dozen countries, including the United States, promised to stop funding fossil fuel projects abroad by the end of 2022. More than 40 countries pledged to phase out coal-fired power, the most carbon-intensive energy source, in the coming decades. The Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance was launched, spearheaded by seven countries who pledged to end new exploration and production of fossil fuels within their borders, and phase out existing production on a timeline that’s consistent with Paris Agreement goals.

A draft text of the conference agreement released early last week even included the line, “Calls on parties to accelerate the phasing-out of coal and subsidies for fossil fuels.” In the final Glasgow Climate Pact, however, the language was watered down to call for phasing down the use of unabated coal — allowing for coal plants with carbon capture systems — and inefficient subsidies for fossil fuels — a qualification with seemingly no agreed-upon definition.

3. The Climate Finance Gap

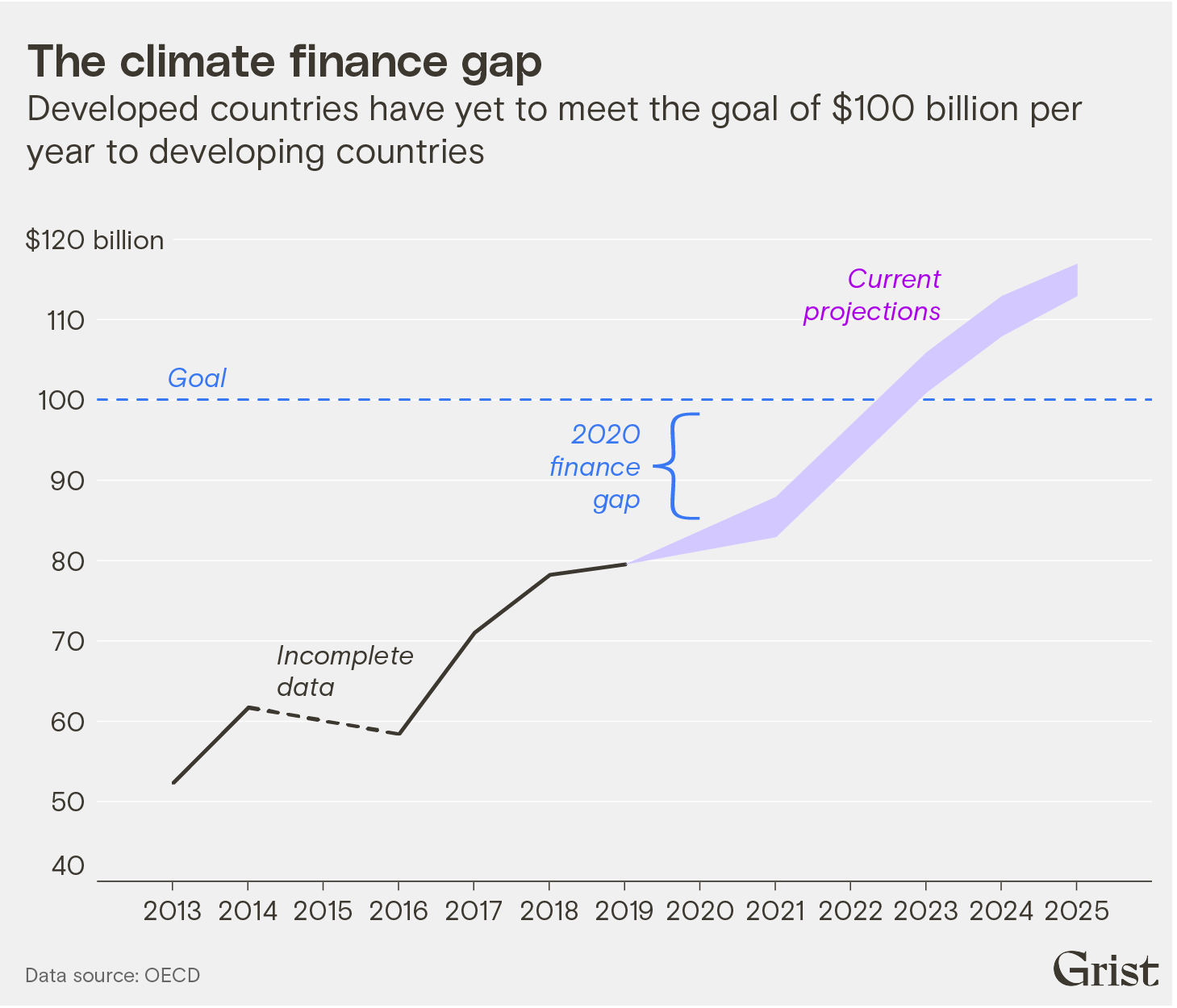

Before COP26, the landscape of climate finance looked pretty bleak. Finance is one of the crucial pillars of the Paris Agreement: In Paris, poor countries agreed to limit their carbon emissions (despite having contributed the least to the climate crisis) as long as developed countries provided them with financial support, both to adapt to climate disasters and to switch over to clean energy.

So far, however, rich countries have been falling short. Despite promises to deliver $100 billion per year in grants, loans, and other forms of finance by 2020, developed countries were $20 billion short as of 2019. (Numbers from 2020 aren’t available yet.) According to a report released just before the conference, the $100 billion goal likely won’t be met until 2023.

After COP26, the situation doesn’t look much better. In Glasgow, countries were expected to chart a faster path to the $100 billion goal and plan how much finance should be allocated after 2025. Some new pledges were made: Japan promised an additional $10 billion, and Scotland made the first-ever contribution to a fund to compensate countries who have suffered from climate disasters. The final text of the conference agreement “notes with deep regret” that the $100 billion goal hasn’t been met, and “urges” developed countries to follow through on the promise as quickly as possible. Still, negotiators for developing countries emphasized that $100 billion is not nearly enough. Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India said in a speech that rich nations should be supplying $1 trillion in finance by 2030, and a group of African nations urged at least $1.3 trillion every year after 2025. But no new finance goal was finalized.

Developing countries also want funds to be more evenly split between adaptation (helping them deal with sea-level rise and extreme weather events) and mitigation (switching to clean energy and cutting emissions). In 2019, only about 25 percent of climate finance went to adaptation projects. While the conference did see record contributions to a U.N. fund focused on adaptation — $356 million — that cash pales in comparison to what is needed. According to one U.N. study, the costs of adapting to climate change in developing countries has already reached approximately $70 billion per year.

The final text of the agreement urged developed countries to “at least double” their contributions to adaptation — a good start. But developed countries will have to actually follow through.