For the better part of a decade, researchers working at the intersection of climate change and human health have been desperately sounding alarm bells about the significant public health threats lurking in every tenth of a degree of planetary warming. Billions of people are at risk from illnesses linked to extreme heat; malnutrition following crop failure; bacteria and viruses that lurk in mosquitoes, ticks, and water; and other climate-driven threats.

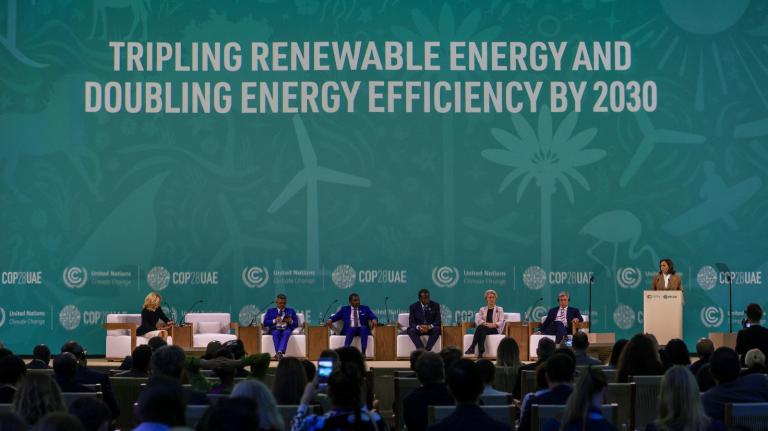

Yet health has never been on the official agenda at the annual United Nations climate change conference, where leaders representing countries around the globe gather to negotiate climate policy. That changed at this year’s Conference of the Parties, or COP28, which is currently taking place in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Sunday was the first ever COP “Health Day,” designed to bring together health and environment ministers from dozens of countries to discuss the health effects of climate change and brainstorm potential solutions.

“For too long, health has been a footnote in climate discussions,” Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, director-general of the World Health Organization, said on Sunday. “No more.”

Health researchers and advocates celebrated the milestone, but when Health Day was over and the resulting commitments were tallied, most emphasized that more needs to be done to protect communities from the health impacts of the climate crisis. “We must not lose sight of the actual negotiations happening behind closed doors, especially on the fossil fuel phaseout, which is what will truly slow and stop climate change from worsening,” said Ramon Lorenzo Luis Guinto, director of the planetary and global health program at St. Luke’s Medical Center College of Medicine in the Philippines and a COP28 attendee.

Even before Health Day began, delegates from 123 countries had already signed the COP28 UAE Declaration on Climate and Health, a nonbinding commitment to protect communities by investing in climate adaptation measures and making health systems more resilient to climate impacts.

The declaration has some significant funding behind it: A coalition of philanthropies and aid organizations, such as the Rockefeller Foundation and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria, collectively pledged $1 billion in new funding to address the climate health crisis. A COP28 spokesperson told Grist that the funding had all been pledged recently — either in the lead-up to the conference or during the event. For instance, the $100 million contributed by the Rockefeller Foundation was announced in September as part of the philanthropy’s five-year “climate strategy,” a Rockefeller spokesperson said.

“Climate change is increasingly impacting the health and well-being of our communities,” said President Lazarus Chakwera of Malawi, one of the initial backers of the declaration. “Extreme weather events have displaced tens of thousands of our citizens and sparked infectious disease outbreaks that have killed thousands more.”

More than 40 banks, governments, and other organizations also signed on to a set of 10 broad principles aimed at guiding international financing for climate and health infrastructure, local projects, and solutions. The principles include supporting the climate and health priorities of countries most affected by climate change and simplifying the processes for accessing available climate and health funds.

On Health Day, global donors including UAE President Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation pledged nearly $800 million to eradicate neglected tropical diseases — a group of 20 climate-sensitive illnesses that affect 1.6 billion of the world’s poorest people, the majority of whom are already extremely vulnerable to the effects of climate change.

Get caught up on COP28

In addition to these landmark pledges, Health Day at COP28 included dozens of health-focused events that took place in an official health pavilion, as well as in other pavilions and tents across the conference. Kristie L. Ebi, a climate and health researcher at the University of Washington who has attended every COP since 1997, called the day a “watershed moment” for her field. “Most of us spent our day going from one pavilion to another to talk about climate change and health,” she said. “The visibility overall of climate change and health dramatically shifted with this COP.”

As prior COPs have shown, making climate commitments is often the easy part — actually seeing them through is much harder. Jeni Miller, executive director of the Global Climate and Health Alliance, said the Declaration on Climate and Health was welcome but cautioned against assuming that the declaration will lead to material benefits for affected populations. “It contains no plans for action right now, and does not have clear goals or targets,” she said. “Nor does it mention the extraction and burning of fossil fuels as the leading cause of climate change and climate-related health threats.” The $1 billion pledge, she added, also does not contain language that describes how developing countries can secure funds for local climate and health projects. How that money will be distributed or used remains to be seen.

Speaking at an event on Health Day, Maria Neira, director of the Public Health, Environment and Social Determinants of Health Department of the World Health Organization, put it succinctly: “This is quite historic,” she said, “but it is just the first day of history.”

More history could be made at COP28. Negotiators are currently debating “an orderly and just phaseout of fossil fuels,” which, if it is adopted, would be the first international deal on the books to call for an end to fossil fuel use. But progress is extremely tenuous — striking a deal on any climate proposal requires unanimous consent from all participating countries. It takes just one dissenting nation to scramble a negotiation, and Saudi Arabia’s energy minister said on Monday that he will not agree to “phaseout” or “phasedown” fossil fuels. Saudi Arabia’s commitment to fossil fuels does not make it an outlier at the conference. Recent reporting revealed the president of COP28, Sultan Al-Jaber, has falsely claimed there is “no science” backing up the idea that eliminating fossil fuels is key to keeping global warming in check.

Still, mitigating climate change is just one part of the challenge the world faces. For the world’s developing countries, which contribute a very small amount to the world’s carbon budget, adapting to the consequences of rising temperatures is now more important than mitigating its effects. That’s why the pledges made at Health Day are significant, Ebi said. Preparing these countries for the health-related climate impacts to come is “fundamental to their national development,” she said. At COP28, the preparations finally got underway.