Under New York’s Major Deegan Expressway in the Bronx, through a set of doors wedged between a parking garage and a pizza shop, a gray and gold throne emblazoned with the letters “S” and “R” sits behind a pair of velvet ropes. The letters stand for “Slick Rick,” one of hip hop’s pioneering rappers, whose hits have been sampled more than 1,000 times by acts ranging from Snoop Dogg to Miley Cyrus.

Slick Rick himself donated the ornate chair to the Universal Hip Hop Museum, the genre’s long-awaited answer to the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, set to open in early 2025 as part of a brand-new development on the other side of the Deegan. The museum will be a slightly belated anniversary tribute to hip hop, which turned 50 earlier this month. For now, Rick’s throne resides at the museum’s pop-up location in the Bronx Terminal Market.

“That basically is one of our most important artifacts,” the museum’s president, Rocky Bucano, told me on a recent visit. Bucano, 63, stands six foot eight, with matching stature in the hip hop world: The trailblazing DJ now works to preserve the larger-than-life legacies of artists like Rick. “When he put out his debut album on Def Jam, he took that throne with him on tour every day,” he added.

It’s no secret that hip hop’s most famous artists often glorify conspicuous consumption. Many of the genre’s lyrics and music videos create an aspirational energy around gas-guzzling luxury cars and private jets. Yet hip hop’s roots lie in activism, and it has long served as a voice on everything from systemic police brutality to discriminatory housing policies. The genre has also been sounding the alarm on what we now call environmental justice.

In recent years, many of hip hop’s New York havens have felt the impact of extreme weather events — from the lethal floods in Run D.M.C.’s Queens to the danger of rising waters in Cardi B’s South Bronx. The creative community has rallied in response to these climate-driven disasters, with stars donating their time and money to relief efforts. And it’s been reflected in the music as well — beyond the occasional nod from the likes of Pitbull, whose 2012 dance-oriented album Global Warming had more in common with Nelly’s hit single “Hot in Herre” than with David Wallace-Wells’ The Uninhabitable Earth, and beyond the nom-de-plume of Migos cofounder Offset (a merely coincidental reference to carbon credits).

Hip hop’s relationship to the environment, both in terms of lyrics and political activism, goes back to its very beginning, when smoke from apartment fires blackened the skies of the 1970s South Bronx. And yet its role in advocating for climate solutions has largely gone unnoticed.

“People have spent time bobbing their heads to our stories of this despair and not seeing it as a call to action,” said Michael Ford, the self-proclaimed “Hip Hop Architect” who designed the museum (and who was featured on the 2019 Grist 50 list). “Now, I think, is this generation’s opportunity to go back and look at 50 years of these unsolicited, sometimes unfiltered and raw stories of environmental injustices and climate change.”

Hip hop dates back to August 11, 1973, when Clive “DJ Kool Herc” Campbell hosted a back-to-school party in a rec room at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue in the Bronx. His revolutionary innovation: physically manipulating two copies of the same record in real time to extend the “breaks,” or the danceable interludes, of popular songs.

Back then, the genre’s activism centered around the built environment, calling attention to egregious living conditions in places like the South Bronx. Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five’s 1982 classic “The Message” served as perhaps the most potent example: “I can’t take the smell, can’t take the noise / Got no money to move out, guess I got no choice.”

“What is today called the climate crisis was in full effect in the underserved communities when this song was released,” said the Universal Hip Hop Museum’s Kate Harvie. “Whatever has been happening to the climate was first to affect unprotected and unrepresented lands.”

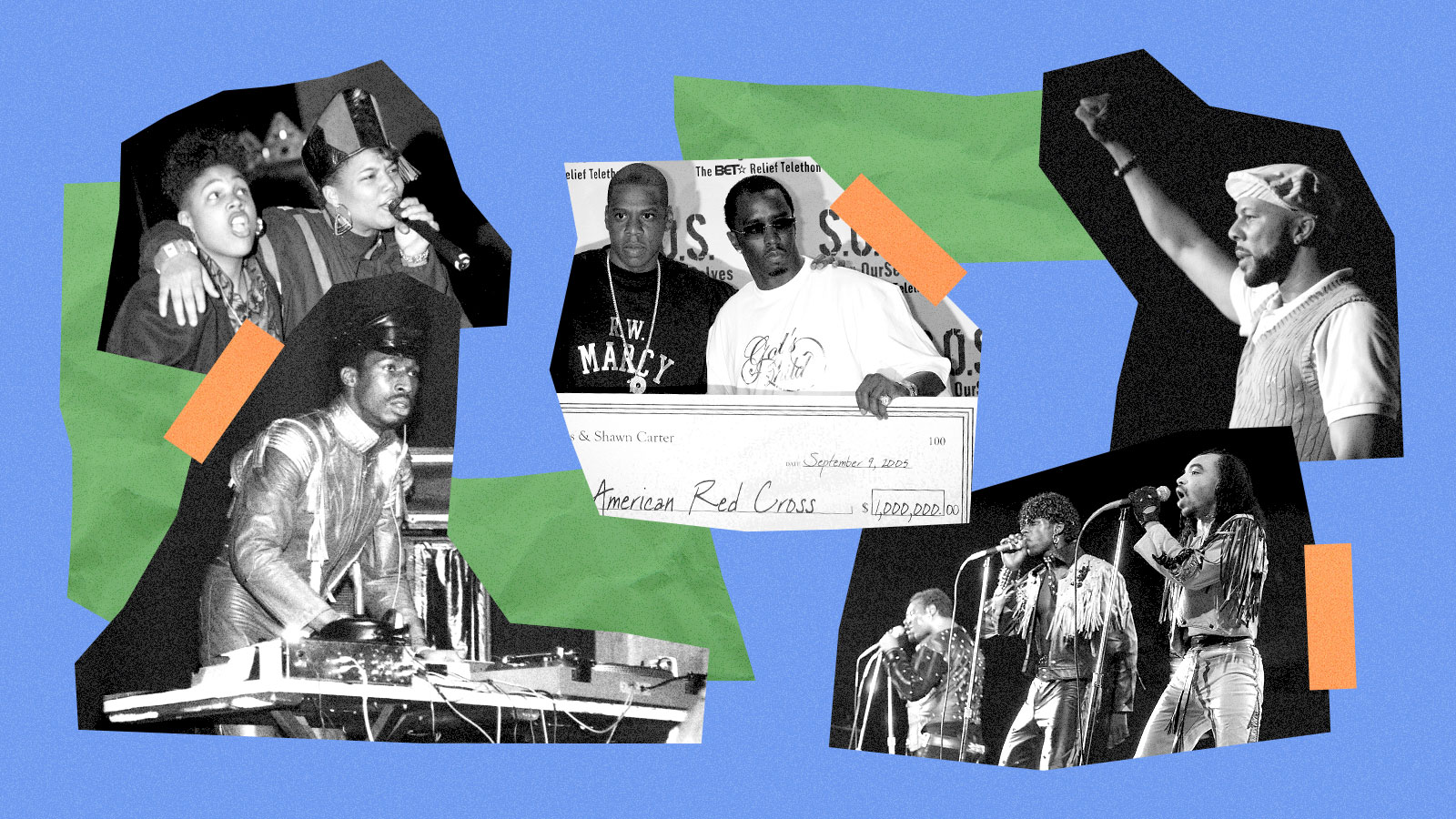

But as hip hop heated up through the 1990s, environmental advocacy took a back seat, at least until Hurricane Katrina hit in 2005. The storm uprooted scores of New Orleans residents, including the founders of Cash Money Records — whose roster, at the time, included Lil Wayne, Nicki Minaj, and Drake. (The company has since decamped to Miami.) Chief executive Bryan “Birdman” Williams told me he lost “20 houses, 50 cars, and memories” in the disastrous flood surge.

Artists like Jay-Z and Diddy donated seven-figure sums to Katrina relief efforts. Others, including Lil Jon and Ludacris, performed on charity telethons to aid disaster recovery. During one, Kanye West, incensed over the federal government’s feeble response in communities of color in New Orleans, famously declared “George Bush doesn’t care about Black people.”

It wasn’t just musicians who were incensed. Reverend Lennox Yearwood Jr., a Louisiana native and president and CEO of the nonprofit group Hip Hop Caucus, also noted the disproportionate damage to New Orleans’ poorest neighborhoods. “Climate justice is racial justice, and racial justice is climate justice,” said Yearwood. “It was the Ninth Ward that was devastated and not the French Quarter.”

Yearwood got his start as a minister in 1994 and served as director of student activities at the University of the District of Columbia before signing on to run Diddy’s Vote or Die! initiative ahead of the 2004 presidential election. He saw unique potential in the hip hop community to mobilize for political, social, and environmental causes — including climate change.

Black neighborhoods often sit in flood-prone areas, a consequence of historic segregation. Environmental racism — which also includes dumping of toxic materials and building highways that cut through communities of color — has led to higher rates of diseases from asthma to cancer. And climate change will continue to have a disproportionate impact, even beyond flooding: If the planet warms by just 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees F), Black people are 40 percent more likely to live in areas with deadly heat waves.

Through the Hip Hop Caucus, Yearwood and others have raised awareness of these realities while also advocating for solutions. Early initiatives included the Green the Block campaign in the mid-aughts, when the Caucus worked with Drake during his tour to “educate his fans about the benefits of going green.” Post-Katrina, Yearwood established the Gulf Coast Renewal Campaign to support survivors. In 2013, the Caucus teamed up with the Sierra Club to protest the Keystone XL pipeline, bringing some 35,000 people to the National Mall — then the largest documented climate protest.

The Hip Hop Caucus’s push for climate justice circled back to the music. In 2014, the group helped organize HOME (Heal Our Mother Earth), an album dedicated to saving the planet. On the track “Trouble in the Water,” the rapper Common delivered the line: “We think our opponent is overseas / But we messin’ with Mother Nature’s ovaries.”

The overlap between hip hop and climate activism is not unique to the United States. Some of hip hop’s most urgent activism is taking place in the Global South, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. In Kenya, there’s rapper King Kaka, the driving force behind a brand called Majik Water, which harvests clean drinking water from the air and aims to hydrate drought-prone communities. Dave Ojay, an artist manager, runs a global environmental justice campaign called My Lake My Future to help save places like Lake Victoria, Africa’s largest.

Some rappers from the continent are even trying to bring the message to U.S. audiences, like Henry “Octopizzo” Ohanga, who traveled to New York for the United Nations’ 2023 Water Conference. Though he grew up in Nairobi, he spent many years of his youth in his familial hometown of Saiya, in Kenya’s rural west. His relatives there have reported rapid declines in crop yields in recent years.

In his song “Hakuna Matata,” a Swahili expression that equates to “no problem,” Octopizzo juxtaposed the familiar slogan with the reality that “drought is killing livestock and humans” while “politicians still in denial are just abusing each other in public.” At the water conference, Octopizzo grew frustrated with the quantity of talk and paucity of action — especially given the confab’s outsized carbon footprint.

“We are converging in New York; we have 7,000 people, probably 80 percent flew in, so already we are f–king up,” he told me. “The hotels, all this money we are spending, we could put it in a bucket, and it could build, like, almost a thousand water spaces in, like, 20 countries in Africa.”

And yet, in many circles, the hip hop community’s cultural and financial contributions to climate advocacy still go unnoticed. Yearwood pointed out that Rihanna doesn’t get much recognition for the $15 million she donated to environmental justice groups through her foundation. (Though Rihanna isn’t a hip hop act by the strictest definition, her example is emblematic of the genre.) Indeed, she’s nowhere to be found on most climate warrior lists, which are typically dominated by white celebrities.

Stars like Diddy and Cardi B supported Joe Biden during his 2020 presidential run; one that resulted in the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, the most consequential climate legislation in decades. Eco-friendly startups have garnered venture investment from rappers like Jay-Z (Oatly and Partake) and Lupe Fiasco (Zero Mass Water).

According to Yearwood, just because these artists don’t “look like” climate advocates, many observers dismiss or minimize hip hop’s role in the climate movement.

“I like Ben & Jerry’s, I have a Patagonia jacket,” he said, referencing brands favored by environmentalists. But he added that the hip hop community has “for many years struggled to find ourselves trying to be part of, or appreciated within, the climate movement.”

With our tour of the Universal Hip Hop Museum’s pop-up exhibit complete, Bucano led me across the street toward the construction site, the first two floors of a 22-story tower, the centerpiece of a $350 million mixed-use development at Bronx Point. The building will eventually include 542 affordable housing units, most of them overlooking the Harlem River. Below the outline of the museum taking shape, backhoes and bulldozers rumbled across the dirt, sloshing through puddles left by recent rain.

As we entered the ground floor, I noticed something on the bare concrete: more puddles. This isn’t necessarily unusual at a construction site, but it’s emblematic of the challenges Bucano and his crew have had to confront. The building is in Flood Zone 1, the designation for New York’s most vulnerable neighborhoods.

It’s the reason the building can’t have a functional basement. Ford, the architect, initially wanted visitors to enter by descending a series of steps, as though walking into a subway station, before coming face-to-face with a real graffiti-covered train. Instead, a subway car will be suspended in the air over the main staircase.

Ford sees his mission as creating the sort of spaces that the Bronx rarely got to have: a place designed for both tourists and those who actually live nearby.

“It’s the Universal Hip Hop Museum,” Ford said. “A large portion of it’s going to be about people who spent most of their formative years living in affordable housing and critiquing affordable housing through their lyrics. But also showing opportunities for young people. You can’t become what you can’t see.”

Bucano would love to see the museum team up with the United Nations for a climate-oriented summit. It’s a topic close to his heart, as he’s already noticed seasons in the Bronx shift compared to his childhood memories.

“Here we are in 2023, and we had our first snowfall at the end of February,” said Bucano. “My sons, those are gonna be the ones that are going to have to deal with climate change.”

After my tour with Bucano, I walked down to the river by myself to get a wider view of Bronx Point. I stood on a little patch of sand and stared up at the museum’s rising outline, trying to imagine where Slick Rick’s throne would eventually reside.

Even on a calm day, the waters lapped against the mossy rocks just a few feet below street level, the most recent high tide already blanketing the outcropping halfway up. It reminded me of something Ford said earlier.

“How do we deal with future tides?” the architect had asked, rhetorically, before offering his answer. “You create a space that’s flexible, that allows you to tell the history — while also leaving room for what’s going to happen tomorrow.”