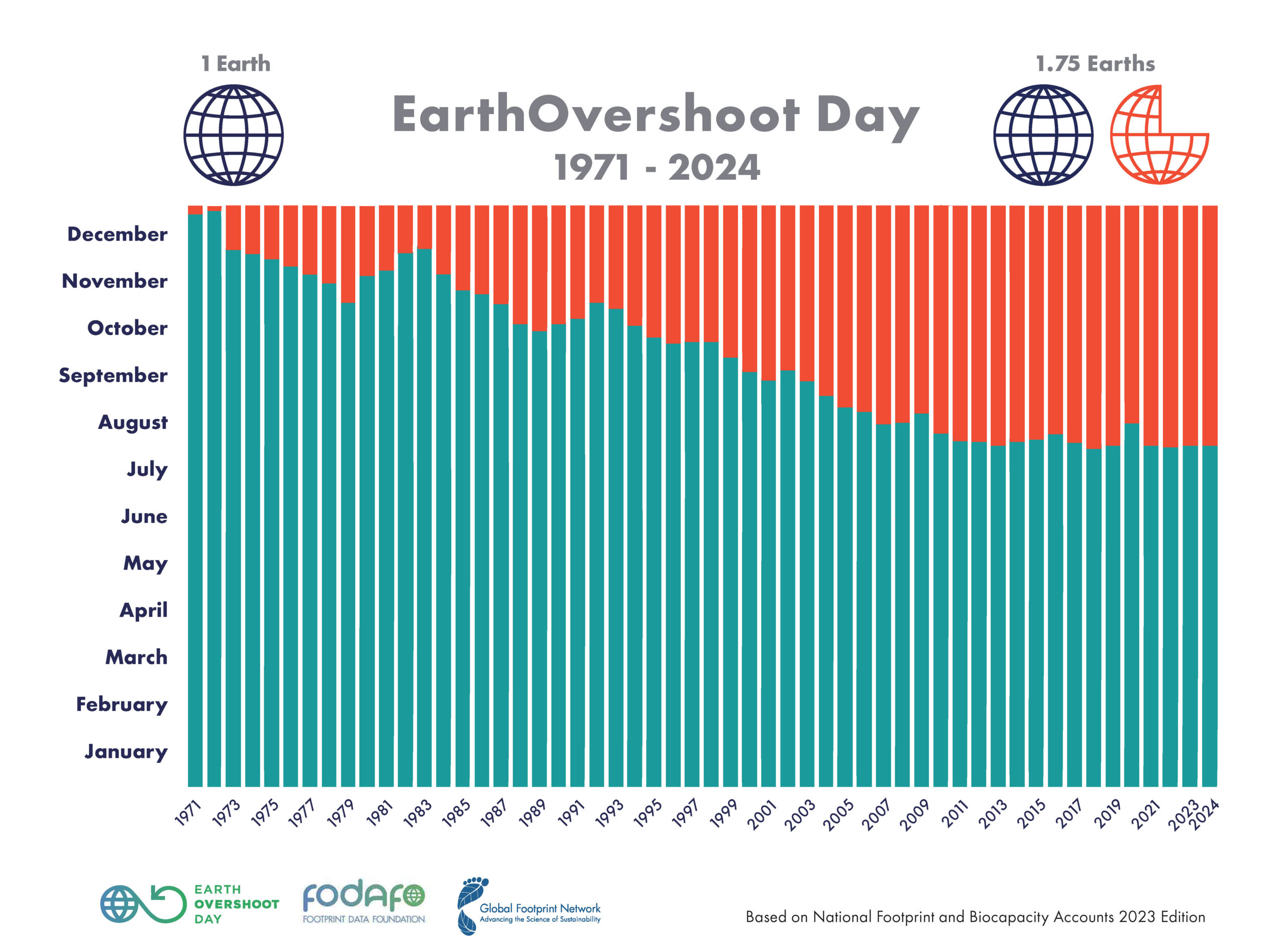

On Christmas Day 1971, for the first time in Homo sapiens’ roughly 300,000 years of hobbling about, humanity’s demands on the Earth exceeded what the planet could provide in a year. That practice has continued, and worsened, for the last half century.

Since the early 2000s, the nonprofit Global Footprint Network has calculated what it calls “Earth Overshoot Day,” the date on which we outstrip our resources each year. At present, human society consumes resources at a rate that would take 1.75 Earths to sustain. So, from August 1 of this year onward, everything we consume adds to our collective debt. In the language of ecological economists: We’re in overshoot.

The date itself is a handy construct, meant to illuminate a larger problem — in reality, the Earth does not reset each year. In the science of planetary accounting, overshoot is more like charging groceries to a credit card after you already blew your monthly budget shopping online. It can’t go on forever. Eventually, those bills come due.

The debt we accrue manifests in three main ways: Waste accumulates, resources deplete, and ecosystems degrade. As these impacts grow, Earth’s ability to regenerate diminishes — what that means in the long run remains unclear, but seems likely that the consequences will grow more severe as our debts mount. “We still do live off the land,” said David Lin, the chief science officer at the Global Footprint Network. Modern life makes that easy to forget — removed, as most are, from the touch and scent of soil and crop. The concept of overshoot was, in a sense, developed to remind us of the demands we place on the land.

Two researchers at the University of British Columbia, Mathis Wackernagel and William Rees, created a metric called the ecological footprint in the early 1990s and, along with it, the idea of overshoot. They intended for this to be a “comprehensive sustainability metric,” encompassing not just a single dimension like greenhouse gas emissions, but the full scope of human impacts on the planet. Wackernagel went on to co-found the Global Footprint Network to track and, hopefully, end the overshoot his metric had revealed.

Today, York University’s Ecological Footprint Initiative has taken over responsibility for aggregating and maintaining all the data required to track, estimate, and project, for every nation around the world, the metrics that can be used to understand and correct overshoot. These metrics include ecological footprint — which describes the cumulative impact, including carbon emissions, of humanity’s urban and industrial activities like logging, fishing, farming, building, and mining — and biocapacity, which reflects the abilities of forests, fish stocks, soils, landscapes, and mountainsides to recover from human demands. Comparing these two metrics determines if we’re in overshoot territory and, if we are, how bad it is.

Crunching these numbers is no simple task. “We stitched together about 47 million rows of input data to generate the system,” said Eric Miller, the environmental economist who directs the Ecological Footprint Initiative, with results going as far back as 1961.

From those tables, the Global Footprint Network and Miller’s team show not just how much we have blown past our planetary budget this year, but also a running total of our debt. And while the date of Overshoot Day has remained comparably stable for the past decade, the debts keep piling up. At the moment, the Global Footprint Network estimates that our debt totals 20.5 Earth-years. So, were all human activity to cease at this moment, the planet would not finish repairing itself from all the harms we’ve done to it until 2045.

Global Footprint Network

Miller noted that discussing things in terms of ecological footprint and overshoot both helps quantify the problem of overconsumption and creates the space to discuss comprehensive solutions to the overlapping ecological crises confronting the planet. It “implies not only reducing absolute emissions,” Miller said, “but also changing the way we use lands and waters.” For instance, it can help us understand how certain climate solutions, like biofuels for aviation, might solve one problem — namely, carbon emissions — while introducing others, like harvesting crops to feed planes instead of people.

From the viewpoint of the ecological footprint, climate change is not the core crisis. Instead, it is merely a symptom of overshoot, in which the waste gases of our overactive industries stockpile in the atmosphere and warm the planet. Biodiversity loss is another symptom of overshoot. As are soil degradation, deforestation, water scarcity, and more.

Yet, though the United Nations climate secretariat has published blog posts about Earth overshoot, the subject has yet to appear in international agreements or national policies. The various commitments that have been drafted and adopted at international, national, state, local, and even corporate levels have placed the emphasis on planet-warming pollution. “So, understandably,” said Miller, “the world is a bit more gripped with the question of greenhouse gas emissions.”

But only attempting to fight the symptoms of overshoot didn’t make sense to Phoebe Barnard, a global change scientist affiliated with the University of Washington. “We all need to be talking about the root causes and becoming aware of them so we can work on them,” she said. She co-founded a nonprofit called the Stable Planet Alliance with two colleagues to focus on the issue of ecological overshoot, as well as the behaviors and practices that have created the problem.

“We think that the Earth is put here as a food pantry for humanity, or that resources are there for our private profit,” Barnard said, “rather than as gifts that the Earth has given us.”

Barnard and her colleagues argue that tackling overshoot requires addressing harmful behaviors and beliefs, like the pursuit of perpetual growth and profit.

They place a particular focus on marketing as both a cause of the problem and a potential solution. The marketing industry has so far acted as an engine of overconsumption by making people yearn for things they had neither the need nor preexisting desire for. But, Barnard said, “What if we could use the means of the marketing industry — which has got the science of behavior change down to a T — to reverse engineer humanity out of its cul-de-sac at the edge of the cliff?”

Global Footprint Network’s approach includes not only raising awareness around Earth Overshoot Day, but also its #MoveTheDate campaign, which promotes actions to reduce overshoot (and “move the date” of Earth Overshoot Day nearer to year’s end). These include promoting things like ecosystem restoration, 15-minute cities, green electricity, and regenerative agriculture. While these overlap significantly with typical climate solutions, discussing these actions in terms of overshoot underscores the fact that we cannot pursue endless growth as we chase aspirations for owning more, nicer stuff to achieve ever greater standards of living.

Both the Global Footprint Network and Barnard also tackle a controversial element that they say is essential to combatting overshoot — population growth and pronatalism, as Barnard and her colleagues describe the desire to expand human populations. In a post for Earth Overshoot Day, Global Footprint Network co-founder Wackernagel acknowledged the “cruel” history of efforts to limit population growth, but argued for reframing the discussion “in a compassionate and productive direction” that also uplifts and advances sex and gender equality.

“Let’s take that conversation away from the old white men who’ve been dominating the conversation, and get women around the world to talk about it,” Barnard said. She pointed out that educating girls and women is often enough to bend birth rates downward, and promote a myriad of other benefits.

But ultimately, the biggest challenge in tackling overshoot — just as with tackling its symptoms like climate change — comes not from understanding the problem or the range of solutions that exist, but implementing them. After all, when we consider what it would take to reduce overshoot and repay our ecological debt, it’s a lot like wondering what you can do to fix your personal finances. “You can ask that in a mathematical sense,” said Lin, the Global Footprint Network scientist. But for each possibility, he added, “Can you do that? Are you willing to do that?” That’s the question.

Read more:

- Can we ‘decouple’ emissions from economic growth? These economists say no.

- Meet the students of the world’s first master’s degree in degrowth

- How to build a zero-waste economy