There are three big, global threats that keep Michele Wucker, a risk expert, up at night: Inequality, financial fragility (that is, the chance of another economic meltdown), and the climate crisis.

And all of these are connected, she says. The rich are getting richer, jetting across the world in carbon-spewing planes, while amped-up hurricanes and drought are hitting poor communities the hardest. Rising seas are swallowing up coastal real estate, with effects that could rattle the financial system.

“Climate change ripples through the entire economy,” Wucker told Grist in an interview. “Any of the other risks you look at in the world are very likely to have some sort of a climate connection.”

Wucker, a strategist and author, has spent decades working on finance, business, and global policy issues. Her 2016 book The Gray Rhino identified big risks that get ignored even though they are probable and predicted — like, say, a global pandemic. She coined the phrase “gray rhino” concept in opposition to the rare “black swan” events that catch everybody by surprise. The way she sees it, the climate crisis is not a slow-moving danger, but a fast-moving one that changes, well, everything.

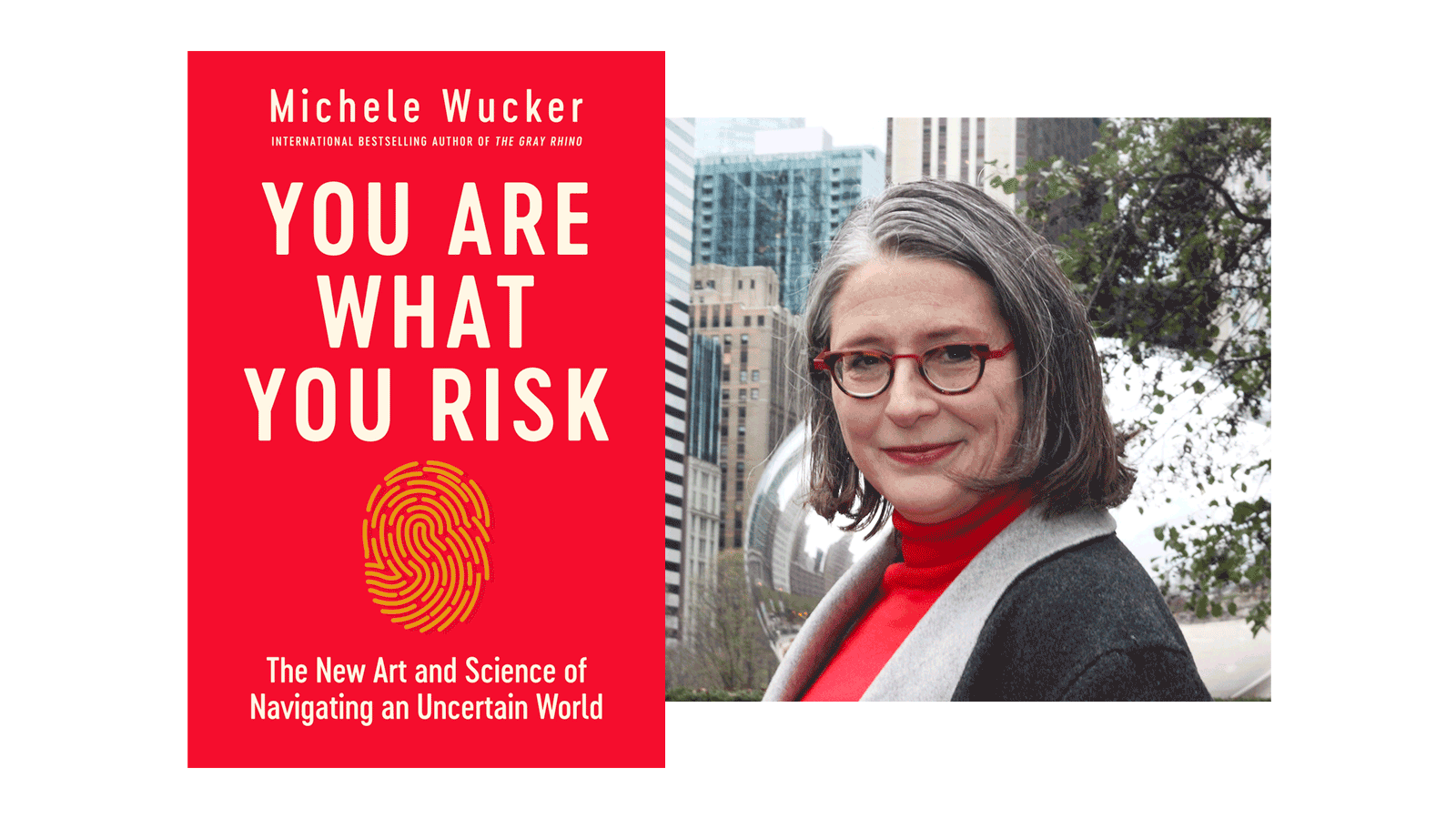

“The world is getting scarier,” Wucker writes in her new book, You Are What You Risk: The New Art and Science of Navigating an Uncertain World. “Often it feels harder and harder to do much of anything to exert control over the risks we face in our daily lives, much less over many of the global risks facing the entire planet.”

You Are What You Risk introduces a new vocabulary for talking about these threats. Everyone has a personalized “risk fingerprint” that describes what kind of risk-taker they are, shaped by their personality, upbringing, and experiences. Strengthening your “risk muscle” can help you make good decisions. The book doesn’t fit easily in any category: It could appear on the “self-help” shelf in the bookstore, or sit in a section devoted to economics, business, or psychology. Her focus zooms in to examine personal predicaments and zooms out to global crises, analyzing how people wrestle with choices and uncertainty.

The book’s release comes at a time when people are starting to pay more attention to the economic ramifications of climate change. “There’s just been a huge surge in attention to climate risk,” Wucker said. Last year, six U.S. senators sent a letter to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac warning that the housing market was unprepared for the devastating floods and wildfires headed its way. Some experts say that a failure to account for these climate risks could fuel a financial crisis like the 2007 subprime mortgage crisis. Investors are beginning to grasp the consequences, Wucker says, pointing to “huge inflows” of money into sustainable investments — such as Environmental, Social, and Governance funds — during the COVID-19 pandemic. Investors are also pressuring businesses to disclose the risks that climate change poses to their operations and how they intend to address them.

Wucker wants to break down misconceptions about climate change, starting with the common idea that it’s a slow-moving threat. “It’s actually not,” Wucker said. “It’s fast-moving, and it’s getting faster and faster.”

In Chicago, where Wucker lives, she says the sunrise looked like the moonrise last fall when wildfire smoke from the West blew across the country. She has a friend in Australia whose brother got injured trying to protect his property from wildfires. Wucker says her asthma has gotten much worse in recent years, to the point that she had to start taking more medication to control it. (Yes, climate change is even making allergies worse.)

Wucker recommends behavioral change — like eating less meat or ditching your SUV for public transit — as a response to a situation that otherwise feels totally out of control. It gives people a sense of agency. “The more each one of us feels that we can contribute to reducing the risks from climate change, the more likely we are to do something about it,” she said. “It creates a virtuous circle.” She cites an analysis from the conservation organization Rare showing that if people started adopting eco-friendly habits on a large scale, their efforts could reduce greenhouse gas emissions worldwide by 20 to 37 percent.

She’s interested in the reasons that some governments take action on climate change while others tend to ignore the threat. It’s partly a matter of values and cultural differences, Wucker reasons in the book, and the risks are objectively different between countries, as are their financial resources. She also identifies one psychological reason that some countries might be more proactive than others. “The greater benefit you see to yourself, the more likely you are to see something as less risky,” she told Grist. That’s true for individuals, as well as businesses and governments.

So countries that make a lot of money off fossil fuels — say, Saudi Arabia — have an incentive to ignore the risks from climate change. Conversely, those that see a benefit to their economy from clean energy are more likely to take the risk of specializing and innovating, Wucker said. Consider Costa Rica, a tiny Central American country that has become a big player in international environmental policy. Costa Rica made “eco-tourism” its brand, and has also committed to total decarbonization by 2050 and regrowing its tropical rainforest.

“Places that see an economic niche for themselves in clean and efficient technologies, if they see something in it for them, they’re more likely to hop on it,” Wucker said.

Near the end of You Are What You Risk, Wucker recounts meeting the teenage climate activist Haven Coleman in 2019. A 7th grader at the time, Coleman was the co-executive director of the Youth Climate Strike in the United States. She had been skipping school every Friday to protest the climate crisis, and had also publicly pleaded with Colorado’s congressional representatives to take action.

“Together, young people and students around the world have been able to draw attention to the climate crisis in a way that we ‘grown-ups’ have failed to do,” Wucker writes. “And why shouldn’t they? It’s their future at risk even more than ours.”