This is the second of two stories examining President Obama’s record on urban issues. Read the first here, and read about the Republican presidential candidates’ positions here.

The conversation about cities today often centers on “creative class” innovation, urban design, and transportation alternatives. But it’s going to take a whole lot more than flashy New Urbanist condo developments and bamboo bikes (awesome though they are) to turn American cities around. Deep seeded social and economic issues still cripple much of urban America, ranging from abysmal public schools to a criminal justice system that creates huge race and class disparities.

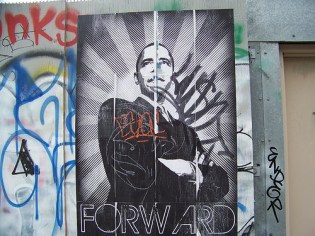

President Obama gets this, at least on paper. Here he is in a speech, made on the campaign trail in 2008, talking about poor urban neighborhoods:

If you are an African American child unlucky enough to be born into one of these neighborhoods, you are most likely to start life hungry or malnourished. You are less likely to start with a father in your household, and, if he is there, there’s a 50-50 chance that he never finished high school and the same chance he doesn’t have a job. Your school isn’t likely to have the right books or the best teachers. You’re more likely to encounter gang activities than after-school activities. And if you can’t find a job because the most successful businessman in your neighborhood is a drug dealer, you’re more likely to join that gang yourself. Opportunity is scarce, role models are few, and there is little contact with the normalcy of life outside those streets.

How do we even begin to deal with this? While there are proven solutions to many of these problems at the local level, as president, Obama has lacked the capital — financial and political — to spread them nationwide. Instead, he has challenged communities to put their strongest ideas forward, and funded the most promising efforts.

It’s a shrewd approach in tough times: Use competition to bring communities on board and ferret out the best proposals, then use what little money you have to create a compelling proof of concept, so that when funding does appear — or when we realize that these approaches actually save money — we can “scale up” and get on with larger reforms. But even these small starts have been hard won, and in some cases, they have failed to address the deeper problems that lie at the root of urban ills.

Take, for example, the Promise Neighborhoods initiative. Built on the model pioneered by Geoffrey Canada at the Harlem Children’s Zone, the program is designed to give poor kids in the hood the same supports that their wealthier (and whiter) counterparts in the suburbs take for granted. Canada starts by training parents-to-be in a program called “baby college,” teaching them about positive ways to discipline children and how reading and talking to your kids gives them a head start in school. He then provides the kids with an intensive educational experience, including after-school and summer programs, carrying them from early childhood all the way through college.

The Harlem Children’s Zone approach is expensive, but it seems to offer a pathway out of poverty for some of the nation’s most challenged kids. You would think that politicians would be jumping at the opportunity to try it elsewhere. Not so much. The Promise Neighborhoods program, created by Obama’s Department of Education, received a scant $40 million in its first two years, despite a tidal wave of interest from the community level — and Obama and Co have had to fight for every penny.

In December, the Republican-run House Appropriations Committee recommended a total budget of zero for Promise Neighborhoods in 2012. Thanks to allies in the Senate, the program netted $60 million for the year — double what it received in 2011 — but it is still far from meeting the demand: There were more than 200 applications this year; only 20 programs will get funding.

Promise Neighborhoods are a part of a much broader education reform agenda that includes greater emphasis on early childhood education, the “Race to the Top” initiative that pushes public schools to improve performance (including on standardized tests, which is another bag of worms entirely), and support for community colleges and job training programs for underserved populations.

Other Obama administration efforts to address ailing cities include:

- The administration has funneled billions of stimulus dollars into poor neighborhoods through programs like the New Markets Tax Credit and the Community Development Financial Institution program.

- Under the banner of Choice Neighborhoods, the Department of Housing and Urban Affairs (HUD) has worked with local agencies and nonprofits to revitalize poor communities by helping create a wide array of services around public housing projects.

- HUD is also developing an “environmental justice strategy,” part of an administration-wide initiative to protect poor communities and people of color from environmental health threats.

- First Lady Michelle Obama has been an outspoken proponent of increasing access to healthy foods in urban “food deserts” and on public school lunch trays (an effort that has not been without controversy).

President Obama has also put considerable energy into creating urban jobs — including green ones. His proposal for an American Jobs Act would pump $17 billion into cities to clean up abandoned housing, rebuild infrastructure, and connect old cities to the new economy. Perhaps it comes as no surprise that Congress, so far, has declined.

“This president clearly has a strong urban agenda,” says Dan Kildee, a longtime politician best known for his proposal to “shrink” aging industrial cities like Flint, Mich., who is now running for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. “But unfortunately, he is now constrained by an obstructionist Congress that makes it really difficult to get anything done.”

But it’s not just Tea Party Republicans who stand in the way. There are also deeply held beliefs about cities and their inhabitants that allow us to continue to treat urban areas — and poor communities of color in particular — as lawless, even hopeless, places. (Few argue this point more eloquently than Baltimore writer Michael Corbin, whose work you can find here.)

Consider, for a moment, that there are currently 2.3 million people behind bars in this country. Half a million people are doing jail time on nonviolent drug charges alone — and perhaps it goes without saying that their ranks include a lot more inner city residents who’ve gotten caught up in the drug trade than suburban pot smokers. Michelle Alexander, a former civil rights lawyer who now teaches at Ohio State University, has dubbed it “the new Jim Crow,” arguing that we use the criminal justice system to deny many African Americans some of the basic rights of citizenship.

Obama has made some admirable progress on the issue. In 2010, his drug czar, Gil Kerlikowske, proclaimed, “I ended the war on drugs.” The administration has begun to shift the machinery of government to treat drug abuse as a public health problem, advocating for more drug courts that send abusers to treatment rather than prison. It helped win a rewrite of federal sentencing guidelines that mandated 100 times more jail time for possession of crack cocaine than for powder — a policy that came down disproportionately on people of color. And it has funneled resources and federal dollars into “re-entry” programs that help ex-offenders find work and community support when they are released.

Still, it is notable that the root of the issue is still taboo on the federal level. A November Gallup poll found that half of Americans support legalizing marijuana (the numbers were higher among young people), and 16 states and the District of Columbia now allow some level of marijuana possession. But although the president himself admits that he “inhaled, frequently” during his younger years, no one in the White House is suggesting that we legalize weed.

“Prohibition is the problem,” says longtime urban scholar Neal Peirce, who is among those who have proposed legalizing marijuana — “not out of any fondness for drugs,” he says, but instead as a way to bring some measure of sanity and justice back to American cities. “But middle class Americans are just shocked by the idea that their kids could have easy access to marijuana or other drugs, so no matter what, we’re going to crack down on it.”

This issue, as much as any, suggests that true solutions for cities lie in breaking down social and ideological barriers — not just at the top levels of government, but at home, too. A truly sustainable future for our society and our cities depends on reviving long- neglected neighborhoods and communities. President Obama has certainly contributed to that effort, but thus far, at least, he has tiptoed around some of the deeper issues that still hold American cities down. Perhaps here, too, the locals will have to lead.