This is the third in a series from my conversation with Atlantic tech channel editor Alexis Madrigal about themes and stories from his new book, Powering the Dream: The History and Promise of Green Technology.

This is the third in a series from my conversation with Atlantic tech channel editor Alexis Madrigal about themes and stories from his new book, Powering the Dream: The History and Promise of Green Technology.

DR: Let’s talk about energy forecasts. They seem to have substantial sway over what we do on energy policy despite always being wrong.

AM: You and I share a fascination with this topic — how something that is transparently and empirically wrong all the time manages to have incredible influence.

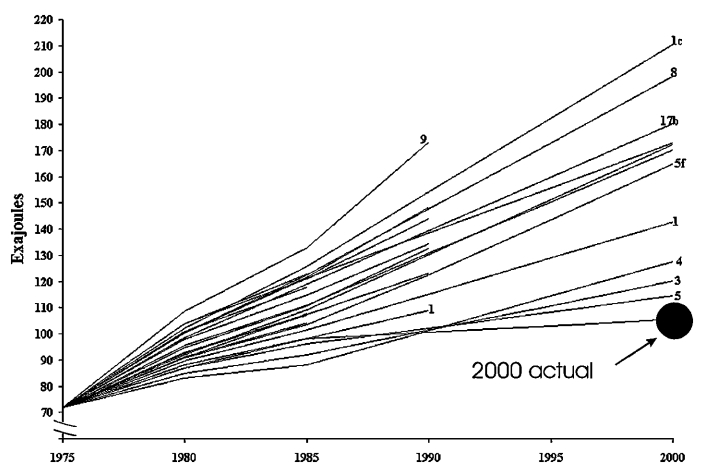

In the 1970s, people were projecting 6 or 7 percent [electricity demand] growth annually. If you have compound 7 percent growth, you look out 20 or 30 years and you’re using incredible amounts of power. When you say we’re going to need twice or three times as much power as we currently have, in 25 years, it limits the type of energy system you can think about building. There is really only one option in that case: You have to build not just nuclear plants, but breeder reactors. The kind of projection they were making, we would have run out of uranium. So if you don’t even think we’re going to have enough uranium, how could you possibly think solar or wind could provide a substantial percentage of U.S. power?

The interesting thing, of course, is that the guys projecting these things were just completely wrong. We use about half of what they were projecting. Even the most restrictive pro-conservation projections made during that time ended up being too high for what we currently use. And I don’t think anyone who drove an SUV to an exurb in 1998 would think we were living in a low-energy society.

Projections of total U.S. primary energy use from the 1970s.Graph: “What Can History Teach Us? A Retrospective Examination of Long-Term Energy Forecasts for the U.S.“

Projections of total U.S. primary energy use from the 1970s.Graph: “What Can History Teach Us? A Retrospective Examination of Long-Term Energy Forecasts for the U.S.“

If you want to imagine the world someone like Glenn Seaborg of the Atomic Energy Commission was imagining, for every single power plant, add another one. Where would we have gotten the money to do this? There was no thought of, well, what is the maximum amount of power people will need? That came in later, when physicists like Art Rosenfeld got involved in the 1970s. They did more bottom-up modeling versus this kind of top-line projecting.

If we want to shout out someone who was good at speaking the language of engineers, Amory Lovins was amazing. He could actually read the spreadsheet and say, OK, if you do this, it’s going to require X number of nuclear reactors and each one of them is going to cost X amount of money. When people actually thought about the whole supply chains that would be necessary, how many reactors would have to be built, where we would have to put them, and all that, it started to seem totally unrealistic. But it took someone knowing how to speak that language to be able to answer this “realist” discourse of a bunch of utility executives.

The fact that a hundred nuclear plants got built in this country is a testament to the resilience of the nuclear power industry, one of the more powerful lobbies you can imagine. But the fact that only 100 got built is a testament to the strength of the arguments of guys like Lovins and Rosenfeld.

DR: What can renewables advocates learn from the extraordinary success of the nuclear lobby?

AM: The first thing is that sometimes the appearance of a breakthrough is as important as a breakthrough. Lyndon Johnson gave a speech in 1965 at Holy Cross basically declaring that there had been a breakthrough in economical nuclear power. That was 1965 — we’d known for 15 years how to use nuclear power. It had been running Navy submarines. We hadn’t commercialized it because there wasn’t a lot of interest on the part of the utilities. It was too expensive.

So Johnson goes out and declares that the Oyster Creek nuclear plant (which, by the way, has the same design as Fukushima) has been a breakthrough. All the American papers go and report it, and they start calling American nuclear scientists, who themselves want to believe that a breakthrough occurred even though the numbers don’t really make sense.

Oyster Creek nuclear power plant, under construction, circa 1965APP file photo

Oyster Creek nuclear power plant, under construction, circa 1965APP file photo

All the French and British scientists are saying, what are they talking about? This can’t be. It turns out GE sold a bunch of these plants at way below cost to give the impression that the price of nuclear power had gone down. They lost billions and billions of dollars — at a time when you could buy houses for $10,000. They were able to get the administration, the political apparatus, believing that breakthroughs were on the way.

The other thing is, during the Cold War it was geopolitically important for the government to be able to promise countries high technology. It was the symbol of what America could offer — the kind of development projects we still promise to places where we want to have sway.

[For the nuclear industry,] getting what I like to call their “future facts” accepted had a lot to do with modeling. That’s where climate advocates have actually done a better job than you might think. The idea that CO2 matters is something that will win — and that’s a key future fact for green-tech advocates. That’s going to be for greentech what the massively overblown [electricity demand] projections were for nuclear power.

One of the cautionary lessons that comes out of that is — and this happened with the nuclear industry too — overpromising can be really detrimental to the cause. The fact that no nuclear power plants were built for 20-plus years is a testament to that. It’s a real possibility that in 15 years we could have built a ton of green technology and then it would stop again. People don’t necessarily think of that as being a real possibility. They figure, once it gets going, it’ll just keep going. But there needs to be some kind of politically sustainable level of support in order to keep the industry from collapsing once it’s been built.

Next: Madrigal and I talk wind power, failure, and wind-power failure. Also, sensors.