It’s long been an open secret that abandoned oil and gas wells are dramatically undercounted in the United States. Now that the federal government is finally offering substantial funding to plug and clean up these environmental hazards, states are finally starting to admit it.

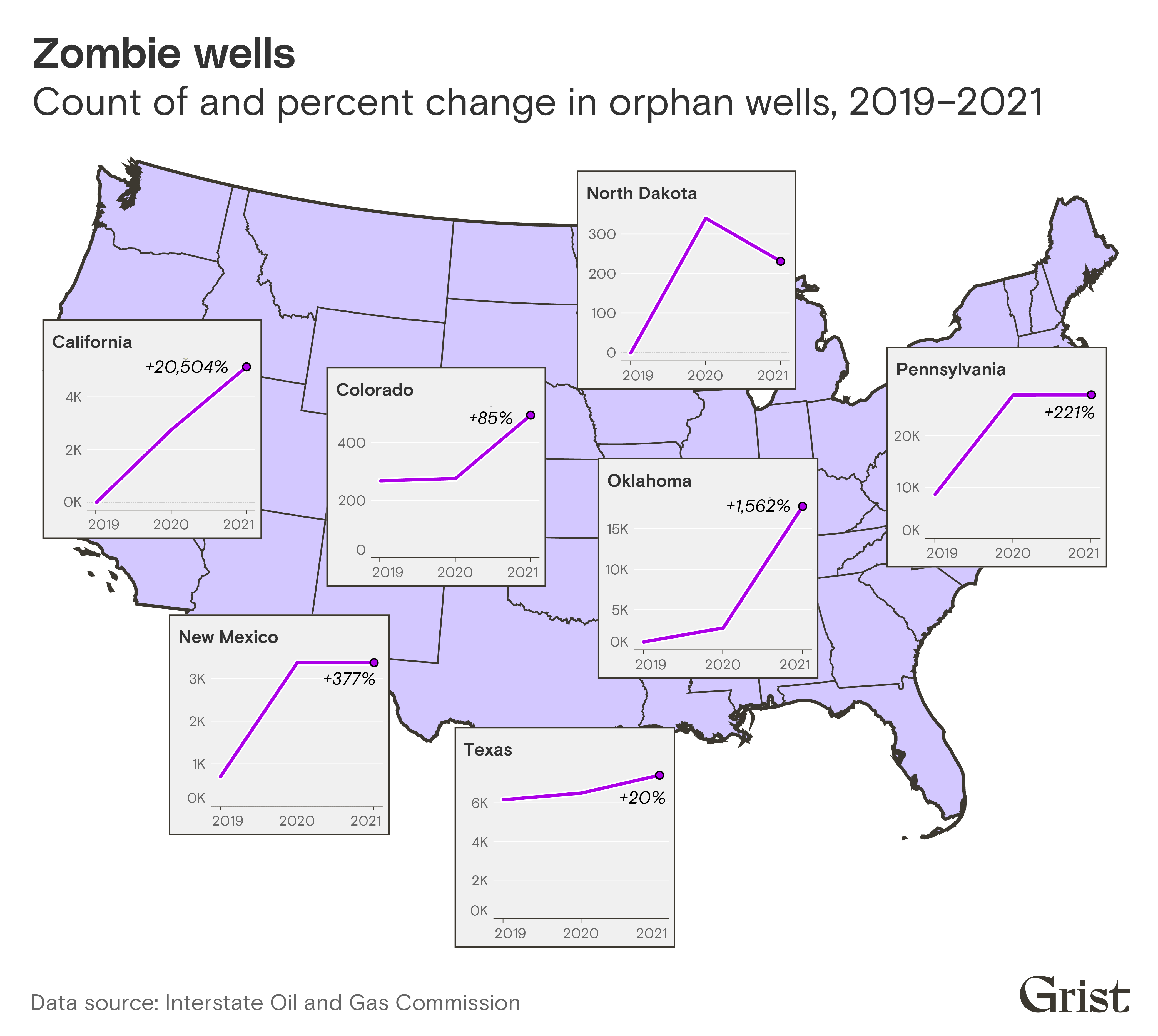

From 2020 to 2021, the number of wells that the state of Oklahoma listed as abandoned — and therefore the government’s responsibility to clean up — jumped from 2,799 to a whopping 17,865. In Colorado, the orphan well tally hovered around 275 from 2018 to 2020 but increased by almost 80 percent last year. In California, the tally almost doubled in the last two years. (It started even lower in 2019, when the state identified just 25 abandoned wells.)

What changed? In 2020, Congress began seriously considering sending states money to plug orphan wells. The proposal had support from both political parties and was ultimately included in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law enacted in November, which set aside $4.7 billion for this purpose. States have long known that their orphan well tallies are outdated and incomplete, but without a source of funding to clean up the wells, many didn’t invest the resources required to identify abandoned wells. That changed as the funding slowly became a reality over the past couple of years.

In Oklahoma, the updated well count has been an even longer time coming. Three years ago, the state legislature funded an overhaul of the information technology systems of the Oklahoma Corporation Commission, the state agency responsible for plugging abandoned wells. As it migrated its oil and gas data to a new database, it found a slew of previously miscategorized orphan wells along the way. Additionally, when oil production plummeted during the early months of the pandemic, inspectors had fewer active wells to oversee and were reassigned to locating orphan wells in the field. Matt Skinner, a spokesperson for the Commission, said that this “perfect storm” of factors was accelerated by the fact that, once found, these wells now had a shot at being plugged and cleaned up.

“We knew the chances were good that this is not an exercise in futility,” Skinner said. “[We knew] it’s quite possible the resources are going to be there, so let’s make sure we have all our ducks in a row.”

The Department of the Interior, which is tasked with distributing the $4.7 billion now allocated for orphan well cleanup, is expected to begin distributing funds this summer. A Grist review of forms submitted to the Interior Department in which states indicated their interest in obtaining federal funding, as well as orphan well tallies reported to the Interstate Oil and Gas Compact Commission, found that official orphan well counts have increased by about 40 percent nationwide in the last year and doubled compared to 2019. That increase was confirmed by the Interior Department earlier this month, when it announced that 26 states had expressed interest in federal funding and had reported more than 130,000 orphaned wells.

“It used to be a larger well count was a sign of significant regulatory failure,” said Robert Schuwerk, executive director of Carbon Tracker’s North America office. “That is still true. However, now there’s an opportunity to get money to plug those wells, so there’s an incentive to get higher numbers to be able to garner more of those federal dollars.”

Orphan oil and gas wells are a climate and public health menace. Abandoned by companies who abscond after fraudulent activity or fall into bankruptcy, these wells quietly belch the potent greenhouse gas methane into the atmosphere and pose a threat to public safety. Last year, a Grist and Texas Observer investigation found that the abandoned well count in Texas and New Mexico is poised to balloon by nearly 200 percent in the coming years. It’s widely accepted that cleanup costs run in the hundreds of millions or billions of dollars nationwide — but both the true cost and the true count are unknown. The EPA estimates the unplugged orphan well count could be as high as 2.1 million across the U.S.

Another explanation that partially accounts for the recent increase in official orphan well tallies has to do with how states define orphan wells, compared to the more expansive definition in the infrastructure law. In some cases, wells have been plugged — meaning filled with concrete to prevent them from contaminating surrounding land and water — but pipes and other infrastructure remain at the surface. Therefore, the new law allows states to seek funds for surface remediation of well sites even if the wells are plugged. For example, Colorado cited 625 orphan wells needing cleanup funds to the Interior Department but reported only 451 orphan wells on state and private lands to the Interstate Oil and Gas Compact Commission. A spokesperson for the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission said that the agency included about 200 wells that had been plugged but required surface cleanup in its notice to the Interior Department.

Of course, oil and gas companies are supposed to be responsible for plugging their spent wells; states are only supposed to step in when operators are defunct or bankrupt. But Schuwerk warned that the additional funding now available could incentivize states to bail out negligent operators. When North Dakota companies claimed that low oil prices during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic prevented them from plugging wells, state regulators took over cleanup of 300 wells even though the companies were operational. They directed $66 million in pandemic relief funds from the federal government toward the effort. Whether or not states will make such allowances with the new infrastructure money remains to be seen.

“That’s something we all should have some concern about, in terms of where the incentives from this money are driving local action,” said Schuwerk.

Clayton Aldern contributed reporting to this story.