Early on in the COVID-19 pandemic, the outlook for renewable energy did not look good. Factory shutdowns in China disrupted the global supply chain for wind turbines and solar panels, delaying construction of projects in the U.S. Clean energy industries across the board started bleeding jobs. Fear spread that the economic recession would put investments in renewables on the back burner.

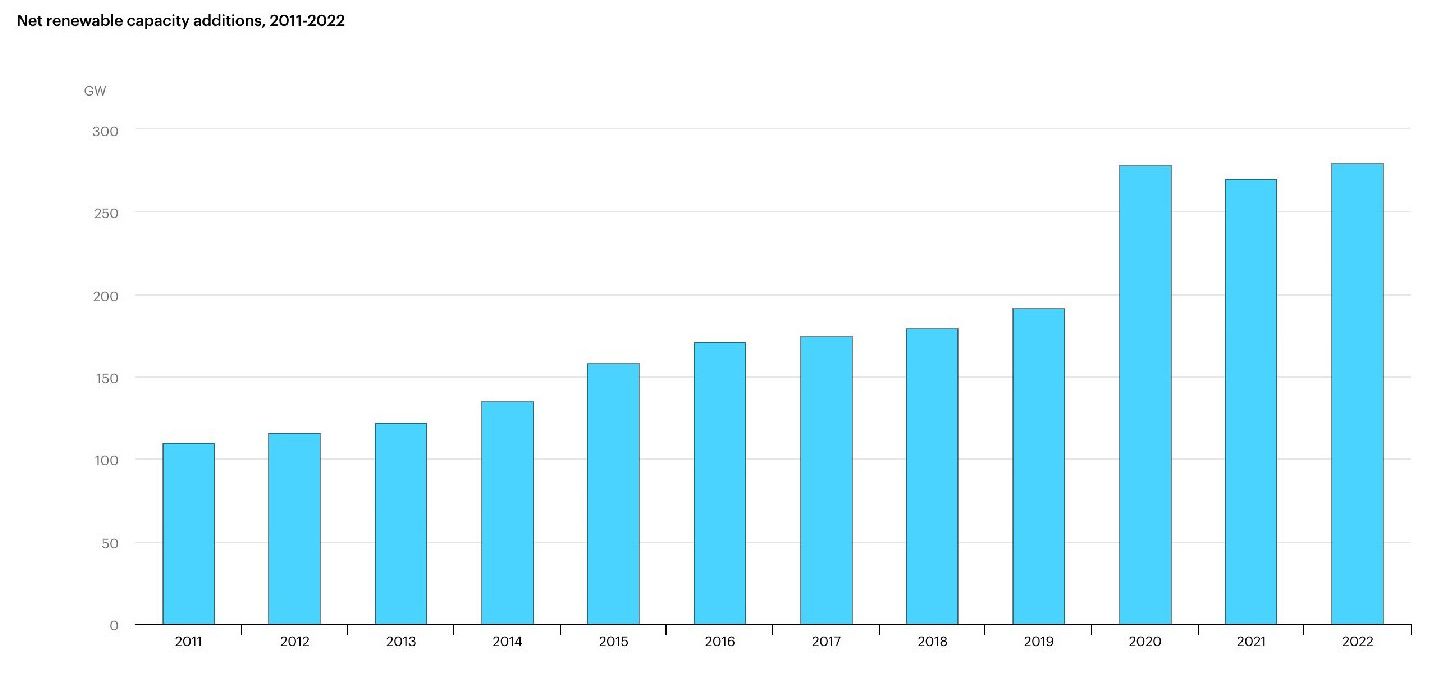

But it turns out renewable energy has not only survived COVID-19 — it’s thrived. A new report by the International Energy Agency, or IEA, found that the world added 280 gigawatts of wind, solar, hydropower, and other renewables to its electrical grids last year. To put that in perspective, that’s about a quarter of the United States’ total utility-scale electricity generating capacity. It’s also a 45 percent increase in new renewable installations from 2019 — the highest year-over-year increase since 1999.

Ultimately, pandemic-induced supply chain slowdowns affected certain countries more than others. India was hit particularly hard, with construction delays and challenges in connecting new projects to the grid leading to a 50 percent decline in new capacity there. Brazil and Ukraine also saw slowdowns. But in the United States, China, and Vietnam, where developers were racing to complete projects in order to meet deadlines for government subsidies, there was unprecedented growth.

China, which has been developing renewable energy faster than the rest of the world for years, was responsible for half of the new installations in 2020. The IEA projects that China will slow down over the next two years but that increased development in other countries — particularly in Europe — will pick up the slack, leading to a similar rate of growth in worldwide renewable capacity for the next two years.

Fears that the recession would shift interest away from investing in renewable energy also turned out to be unfounded. The IEA found that governments awarded nearly 75 gigawatts’ worth of new renewable energy contracts in competitive auctions last year, a 20 percent increase from 2019. Corporate procurement of renewable energy also increased by a record-breaking 25 percent.

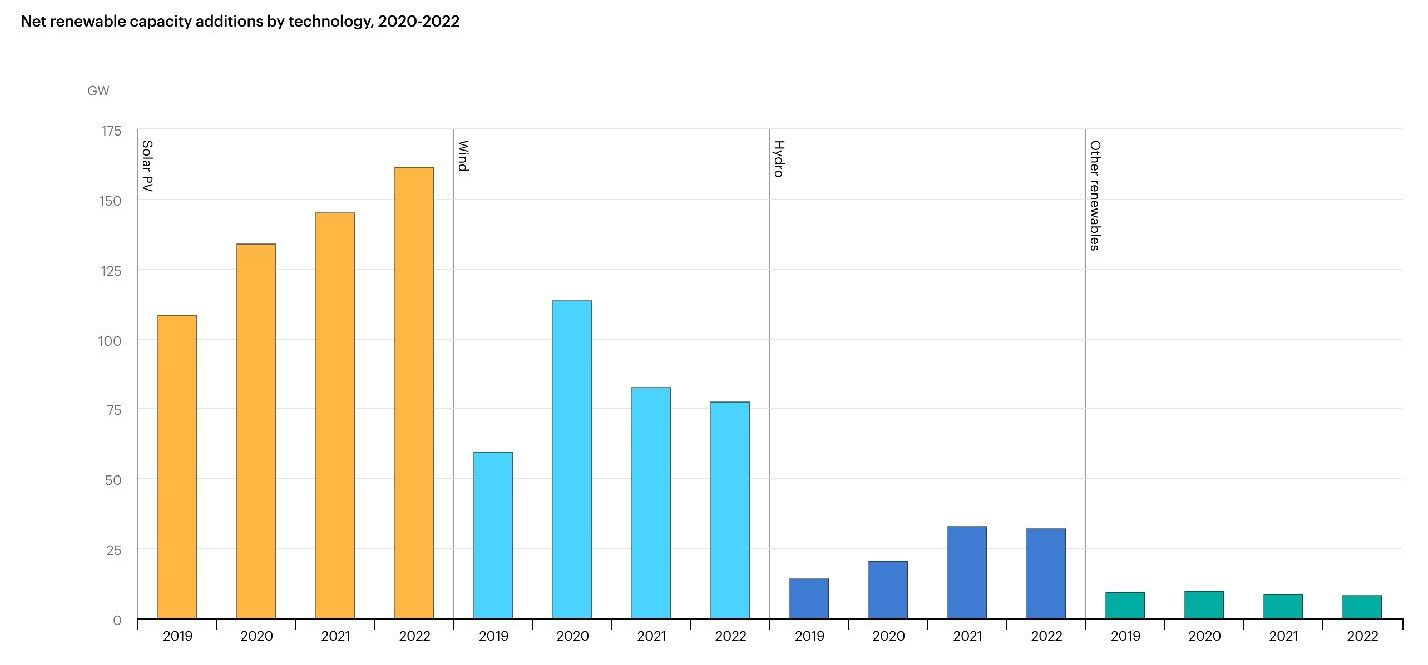

Solar power grew more than any other form of renewable energy last year, accounting for nearly 50 percent of the capacity additions. The IEA reports that solar has become the cheapest form of power in many countries and will continue to grow at a faster clip than other technologies.

In the United States, solar is expected to continue to grow for the next two years, but onshore wind development is expected to decline in the near term. That’s because a key tax credit offered to wind developers was originally scheduled to expire in 2020. Congress extended the credit in December, but the IEA does not expect that to drastically change projections for 2021 and 2022.

However, one thing that could speed up progress in the U.S. is if Congress passes policies proposed as part of President Biden’s infrastructure plan. The plan includes a 10-year extension of clean energy tax credits that would give developers more certainty about their net costs. It also proposes a “direct pay” system for these tax credits that would allow renewable energy developers to receive full tax refunds for projects regardless of their tax liability. A similar provision included in then-President Barack Obama’s 2009 Recovery and Reinvestment Act gave wind a big boost in the following years.

The world needs rapid and continuous growth in renewable energy in order to meet international emissions reduction targets and slow climate change. But one should not mistake the upward trend in renewables for emissions reductions. Renewables are meeting new energy demand, but they aren’t necessarily leading to a phase-out of fossil fuels, or at least not everywhere. The IEA expects 270 new gigawatts of renewable energy in 2021, but it also projects a historic rise in global carbon dioxide emissions due to an expected 4.5 percent increase in coal demand.

“This is a dire warning that the economic recovery from the Covid crisis is currently anything but sustainable for our climate,” said Fatih Birol, the IEA Executive Director in a statement about the emissions project last month.