Say you’re walking down the street in a random neighborhood somewhere in the United States, and you see a house with solar panels on the roof. Can you make any assumptions about the people who live inside? Is the decision to install rooftop solar the mark of a liberal climate warrior, or does it cross party lines?

Those are two of the questions Matto Mildenberger and his co-authors set out to answer in a new study published in Nature Energy last week. “I genuinely didn’t know the answer,” Mildenberger, a professor of environmental politics at UC-Santa Barbara, told Grist.

Using the satellite tool Google Project Sunroof, which maps existing rooftop solar installations, the group found more than 4,000 houses with rooftop solar and 4,000 neighboring houses without solar. They then matched the addresses with political and voting behavior data purchased from a political data company. For each address, they acquired information like party affiliation, voting activity, whether the household rented or owned the property, and basic socioeconomic and demographic data. After crunching the numbers, they found that 34 percent of properties with solar belonged to registered Democrats, and 20 percent belonged to registered Republicans. (The remaining 46 percent were independents or unregistered.) The neighboring, non-solar houses were split along similar lines.

“We’re not actually seeing Democrats have solar and Republicans don’t,” Mildenberger said. “This is reasonably strong evidence that people are not deciding to adopt solar out of some sort of ideological preference.” He attributes the higher number of Democrats with panels to the fact that areas with more Democrats, like California, also tend to have more solar panels in general.

Mildenberger’s work builds on similar findings from an earlier study by a group out of UC-Berkeley looking at political affiliation and rooftop solar in just two states: Texas and New York. While those researchers didn’t have the granular address data that Mildenberger’s group worked with, they found that Republican-majority communities had installed rooftop solar panels at the same or greater rates than Democratic-majority communities.

“Both papers are pointing to this fact that Republicans are given this image that they are not participating in the solar revolution, but they are,” said Deborah Sunter, a co-author of the earlier paper who’s now an assistant professor at Tufts. “There’s a mismatch between what the constituents are doing and what the politicians are advocating for.” In several states, like Ohio and Kentucky, Republican-led legislatures are rolling back incentives for renewable energy.

But the new study suggests that could change. That’s because people with rooftop solar were significantly more likely to vote than those without.

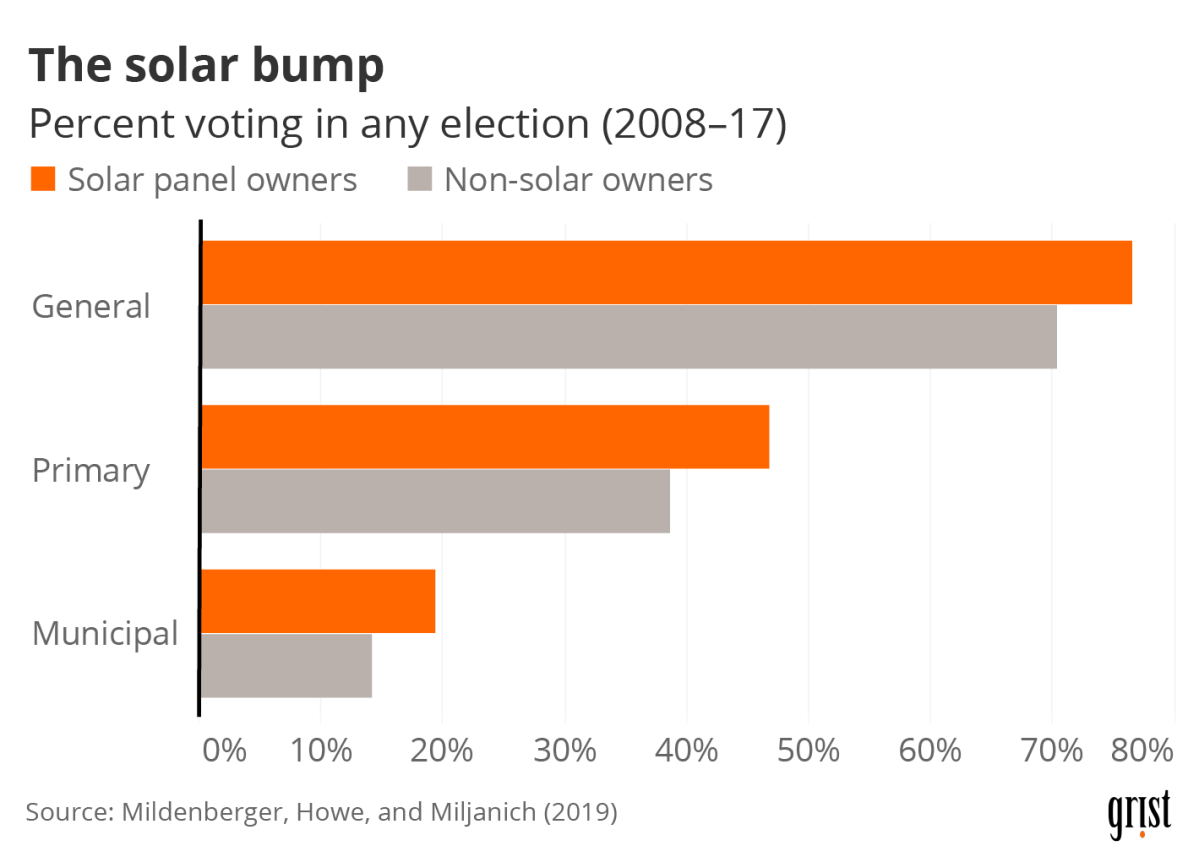

In general, primary, and municipal elections between 2008 and 2017, households with solar panels consistently voted more frequently than households without solar installations. Why does that matter? If conservatives with solar are more likely to hit the polls than their neighbors, they also might be likely to lobby their politicians to support clean energy policy.

There’s a theory in political science called “policy feedback”: When a new policy is implemented, and people who may not have supported that policy in the past begin to benefit from it, they might form new coalitions to protect and strengthen the policy. In short, “a new policy creates a new politics.” With solar, the federal solar tax credit and net metering policies created a financial incentive to install rooftop panels, which may have led residents who couldn’t care less about the environment to invest in them. Now, Mildenberger said, these folks have a vested interest in protecting that investment, and may put more pressure on their representatives to support clean energy policies.

“I think that we’re seeing that this technology has the potential to scramble some of the ideological cleavages that exist around climate and energy,” said Mildenberger. “It may be an on-ramp for Republican primary voters to push Republicans to maintain or adopt a more aggressive pro-renewable stance.”

The study illustrates that Republicans are active participants in the clean energy transition, but it’s less clear why. There’s a range of possible motivations driving the decision to invest in solar: it might make financial sense, or someone might like the autonomy of generating their own energy or the idea of being more resilient in the face of power outages. Or they might just think it’s the right thing to do. Why Republicans install solar panels is one question Mildenberger plans to look into next.

Regardless of the reason, Sunter said the new findings are heartening. “It’s really great to see that our country isn’t as divided as I think society or the media is trying to push us to believe that we are,” she said.