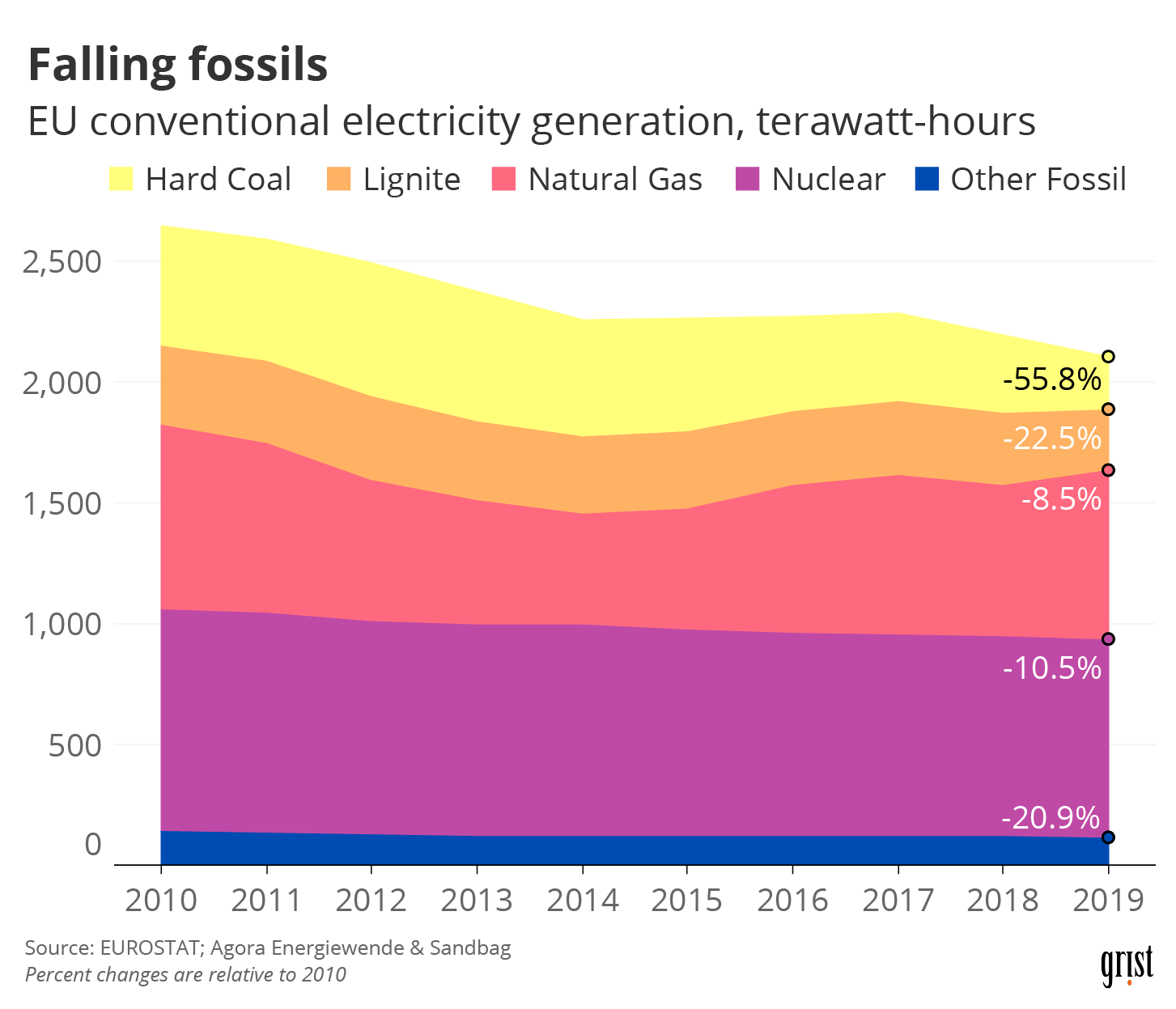

The European Union has undergone a pretty dramatic transformation as of late — and we’re not talking about Brexit. The group of member states, which pledged as a collective to become carbon neutral by 2050 as part of Europe’s Green Deal, cut carbon emissions from electricity by a whopping 12 percent in 2019, according to a report compiled by the European thinktanks Agora EnergieWende and Sandbag. Coal use, in particular, plummeted by about 25 percent.

“What surprised us most was the magnitude of the collapse of coal and the accompanying decrease in CO2 emissions,” said report coauthor Fabian Hein. “The speed of it was impressive.”

Clayton Aldern / Grist

The dramatic drop in CO2 — the equivalent of cutting the U.S. state of Georgia’s annual carbon emissions — can be linked to both the E.U.’s commitment to making Europe “the first carbon-neutral continent” and a steep increase in the market price of carbon, which drove the cost of polluting to its highest level since 2008. Aggressive onboarding of wind and solar also helped renewables overtake coal for the first time as the largest contributor to the electricity sector.

While that’s good news for the planet, the numbers don’t guarantee Europe will continue to make steady progress toward its goal of a carbon-neutral economy by 2050. A milder-than-usual winter last year helped lower the demand for electricity slightly across every country included in the 2019 report. And a closer look at the data shows that while coal power is falling fast, natural gas use has actually crept back up since hitting a low point in 2014. Not all E.U. nations are making the same progress in renewable development. Many Eastern European countries continue to fall far behind their wealthier neighbors, like Germany, the U.K, or the Netherlands.

The E.U. still has a lot of work to do to hit its 2030 benchmarks, including rapid improvements in energy efficiency and transportation. But in a speech about the challenges Europe still faces in its energy transition, Frans Timmermans, executive vice president of the European Commission and the head of the European Green Deal, singled out power generation as a reason to believe the E.U.’s can achieve its larger climate goals.”

That is one area at least in which progress is “go[ing] much faster than anybody had anticipated,” Timmermans said.