If you encounter it at all, it might be on the highway. Driving down I-95 from Boston to New York City, you’ll pull into a rest stop and notice a sign advertising “clean hydrogen fuel.” As you pass an 18-wheeler parked in the lot, you might catch a glimpse of a decal near the gas cap — green letters that read, “powered by H2.”

On the other hand, it might be much closer to home. A new industrial park is proposed in your community. The design plans include a cluster of nondescript buildings, some large metal tanks, and an array of wind turbines or solar panels. The project may bring benefits like jobs and funding for local initiatives. But some are worried about environmental risks and property values. The specter of a new hydrogen pipeline begins to haunt local headlines.

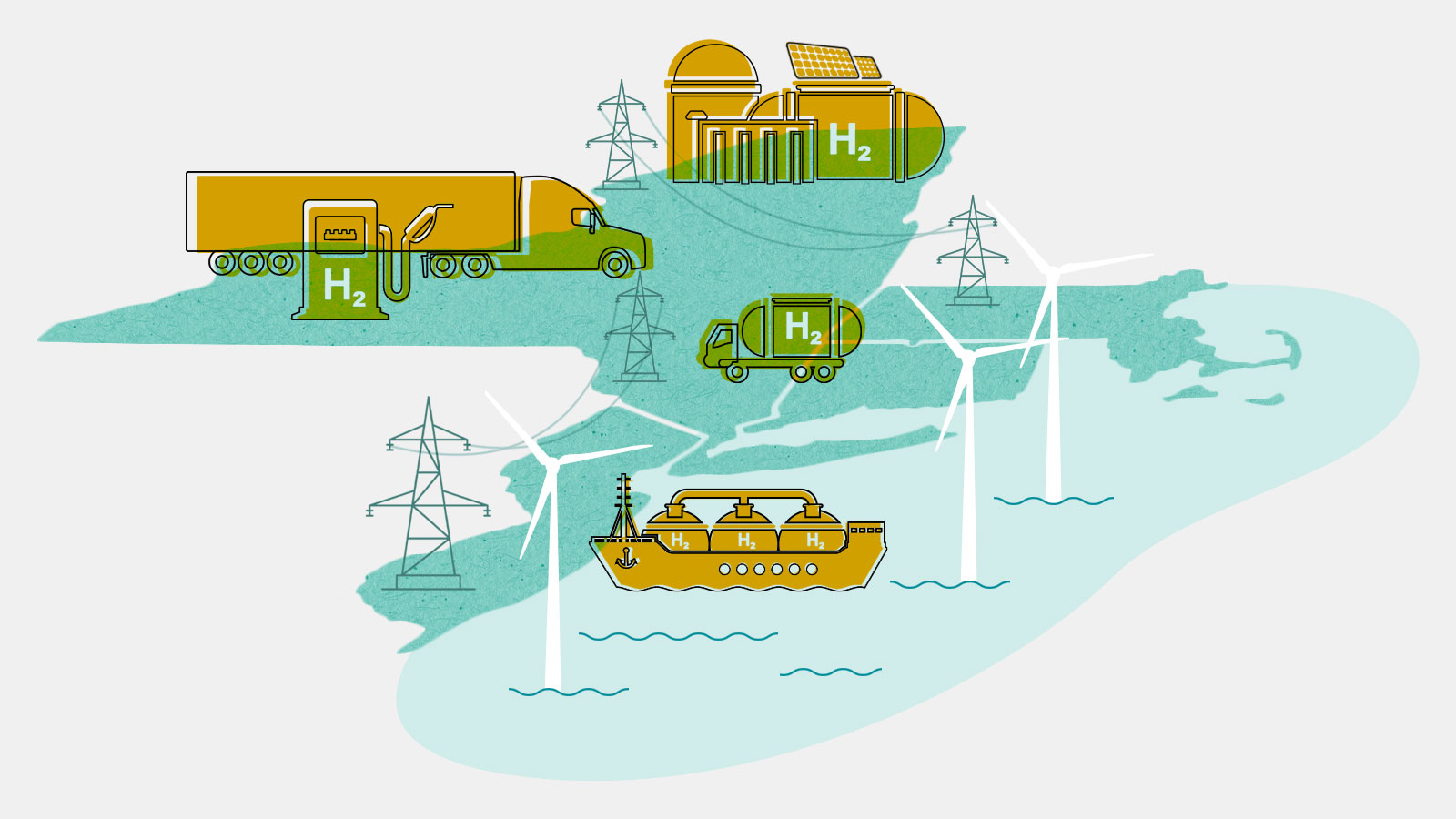

These are just a couple of the many possible ways people in the Northeast might experience the energy transition happening around them if the Department of Energy chooses the region to become a “clean hydrogen hub.”

“It does remain really abstract, at this point,” said Rachel Fakhry, who leads the hydrogen and energy innovation portfolio at the Natural Resources Defense Council. “We are seeing some hubs and clusters pop up globally, but it’s still really a nebulous concept.”

The bipartisan infrastructure law that Congress passed in 2021 gave $8 billion to the Department of Energy, or DOE, to support the development of at least four regional “hubs” for clean hydrogen, which is seen as a promising alternative fuel to fossil fuels for a variety of industries. And while DOE has yet to begin soliciting proposals, or even to define what a “hub” is, governments and businesses all over the U.S. are already coming together to vie for the funding.

The word “hub” may bring to mind a relatively small area with a high concentration of activity, like the downtown of a city or a port. But some of the potential hubs, like a proposed partnership between New York, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New Jersey, shows how sprawling the concept could turn out to be.

“This is more than just a project or a demonstration, it’s really a broader regional ecosystem that is intended to be advanced,” said Doreen Harris, the president and CEO of the New York State Energy Research Development Authority, or NYSERDA.

So what might that ecosystem look like? In some parts of the country, where hydrogen is already a part of the economy, it might look like converting existing infrastructure and industries to cleaner processes. But in the Northeast, it means building something totally new. Grist spoke to state officials, industry representatives, and climate policy experts to begin to piece together a picture of how hydrogen could transform the region. Their answers point to bigger questions about hydrogen’s role in the energy transition, and the extent to which it might either replicate today’s fossil fuel infrastructure or play more of a supporting role in the energy economy of the future.

Hydrogen fuel can power many of the same activities that fossil fuels power today, without releasing any climate-warming gases. But unlike fossil fuels, which can be dug out of the ground, hydrogen has to be manufactured. Today, it’s produced from natural gas and coal in an energy-intensive process that emits carbon. More than 2 percent of global emissions currently come from hydrogen production. Most of the hydrogen we make is used as an ingredient in oil refining, fertilizer production, and other industrial processes.

The trick to cleaner hydrogen is either to add equipment to the traditional hydrogen production process to capture the emissions, or to eliminate them altogether by producing the fuel through a different process called electrolysis, which uses electricity to split water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen. If the electricity comes from a clean source, like wind turbines or a nuclear plant, the hydrogen will also be emissions-free.

Currently, there’s a chicken-and-egg challenge to producing clean hydrogen because it’s still more expensive than fossil fuels themselves, and there’s little demand for it. The DOE’s hubs program is designed to build up networks of producers, users, and the infrastructure required to link them, all at the same time.

The program will also begin to answer key questions about where hydrogen can compete with other climate solutions. There are many industries where clean hydrogen could replace fossil fuels, but other solutions, like using clean electricity directly, might be more efficient and economical. The hydrogen hub initiative could help prove which applications make financial and practical sense.

“It’s really a demonstration program,” said Emily Kent, a policy manager for zero-carbon fuels at the Clean Air Task Force, an environmental nonprofit. “On the production side, we’re demonstrating that we can produce hydrogen with really low greenhouse gas intensity. On the end use side, we’re demonstrating that we can use hydrogen in new ways than we ever have before.”

New York Governor Kathy Hochul announced the agreement between her state, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New Jersey to jointly apply for the DOE funding in March. The press release named 40 additional partners, including hydrogen technology companies, utilities, and universities, that will contribute to the vision of a northeast hydrogen hub.

The four states in the Northeast partnership all have laws in place requiring that they rid their electrical grids, roads, and much of the rest of their economies of carbon emissions in the next few decades. Harris of NYSERDA said New York is focusing on converting as much of the economy to run on clean electricity as possible. “But there’s places where fuels are useful,” she said.

Some of those places include medium- and heavy-duty transportation, like those semi trucks parked at the rest stop. One of the partners listed in Hochul’s announcement is Cummins, a company that builds engines for delivery trucks, buses, heavy-duty trucks, ships, trains, and agricultural and construction vehicles. “We are interested in decarbonizing our industry and have a plan to get to net-zero emissions by 2050 across all our applications,” a spokesperson for the company told Grist. Cummins has already built fuel cells that run on hydrogen to power trains and trucks in Europe and a ferry in San Francisco. (Fuel cells can convert the chemical energy in a fuel like hydrogen or methane to electrical energy, without any combustion.)

But heavy-duty trucks are a good example of the uncertainty around where and how hydrogen will win out over electrification. Companies like Volvo and Tesla are investing in developing trucks that run on batteries. “There’s still a question mark,” said Fakhry of the Natural Resources Defense Council. “Will hydrogen be able to outcompete electric trucks? We don’t know, because electric trucks are making very strong advancements.” Policy is going to play a big role in answering that question, she said, including whether the DOE decides to prioritize investments in hydrogen trucking.

An area where clean fuels like hydrogen are more likely to outcompete batteries is the shipping industry. New York and New Jersey host the largest container port on the East Coast. “I know that we’re not going to be crossing the Atlantic Ocean by battery anytime soon,” said Arne Ballantine, the CEO of Ohmium, a company developing electrolyzers to produce clean hydrogen that also signed on to the Northeast hub as a partner. Today’s batteries are simply not advanced enough to power a ship weighing hundreds of thousands of tons.

Clean hydrogen could eventually fuel maritime shipping vessels as well as some activities onshore, like the heavy-duty machinery used to load and unload cargo. This transition could have measurable health benefits for neighboring communities that are currently polluted by dangerous emissions of sulfur oxides, nitrogen oxides, and particulates as ships idle in the harbor. But that depends on whether ships transition to fuel cells, which wouldn’t emit any pollutants, rather than more traditional engines burning hydrogen, which would.

There are other ways that clean hydrogen could transform the Northeast that may be less visible, like in power generation. There is fierce debate about the role hydrogen should play on the electrical grid, since using renewable electricity directly is always more efficient than using that electricity to make clean hydrogen, only to turn the hydrogen back into electricity. Hydrogen’s main advantage there is that it can be stored in large quantities for long periods of time, and turned back into electricity as needed.

Harris also said the Northeast could use clean hydrogen in industrial processes that require extremely high temperatures that are harder to achieve with electricity. Nucor, a steel company with plants in upstate New York and Connecticut, is listed as a partner on Hochul’s hub announcement. The company did not respond to Grist’s request for comment on whether or how it might use clean hydrogen, but studies have found that clean hydrogen presents one of the most promising pathways for cutting emissions from steelmaking.

As for the production side, Harris was clear that the Northeast hub proposal would focus on hydrogen made from electricity, not from natural gas. That means drawing on the vast hydropower resources that already exist in the area, as well as new solar and onshore and offshore wind farms that will be built in the coming years.

But it could also mean the region will have to build a lot more solar and wind farms than might otherwise be needed solely for electricity. In comments to the DOE, the Clean Air Task Force urged the agency to prioritize hydrogen producers that use “additional” renewable energy, meaning those that build their own renewables or sign purchase agreements with renewable developers, rather than those that simply tap into existing clean energy sources. “So that you’re not taking it away from helping to clean up the electricity sector,” explained Kent of the Clean Air Task Force. “You’re adding on to that.”

There’s a lot of variation in what these hydrogen plants could look like. New York is already subsidizing construction of “the largest green hydrogen plant in North America,” in Genesee County, between Buffalo and Rochester. It will be built and operated by a company called Plug Power. Site plans presented to the county planning board included a 40,000-square-foot building housing the company’s electrolyzers and a 68,000-square-foot “compressor building.” Company representatives told the board the hydrogen will be transported by tanker truck to customers throughout the Northeast, including Walmart, Kroger, Home Depot, and Amazon, which will use the fuel to power forklifts and other warehouse machinery. The site will use 280,000 gallons of water per day.

Hydrogen production plants could also be much smaller. Ohmium’s electrolyzers fit in a cabinet that’s about the size of two refrigerators, Ballantine said. The system is modular, meaning it can be stacked to produce more or less hydrogen, and can be installed directly on site where the hydrogen will be used.

Depending on how the vision for a Northeast hub evolves, it could also mean blending hydrogen with natural gas in existing pipelines to transport it to power plants and other gas users. Many environmental groups oppose this idea for the same reason that the gas industry likes it: It would extend the useful life of those pipelines and the use of natural gas.

While hydrogen can be transported via truck or produced near its customers, developing new pipelines in the region to carry the fuel from where it’s produced to where it’s used could also be on the table.

But Fakhry said that it was too early to start making decisions about pipelines now.

“In a market that is still so new, where we don’t really know exactly where the demand comes from, and where the supply’s going to come from, and we still need to do a lot of learning, making those early, big investments in pipelines is really risky,” she said.

The DOE will put out an official funding announcement for the hydrogen program later this year, which is expected to contain more information about what the agency will be looking for in proposals. But it’s unlikely that it will resolve many of these uncertainties around hydrogen. That’s for the hubs themselves to do.