This coverage is made possible through a partnership between Grist and WABE, Atlanta’s NPR station.

As more and more data centers crop up throughout Georgia and the Southeast, a recent study finds they may need less energy than the industry and utilities have been predicting. That could have substantial implications for energy bills and the planet.

Data centers — especially the biggest ones, known as hyperscalers, used for high-powered computing like generative AI — use a lot of energy. And major utilities like Georgia Power have started expanding power plants and building other infrastructure to fuel them. Late last year, the Georgia Public Service Commission approved a staggering 10 gigawatt expansion for Georgia Power to meet projected demand that’s mostly from data centers, after previously greenlighting new natural gas-fired turbines for the same reason.

But the level of growth that Georgia Power and other southeastern utilities are planning for only has about a 0.2 percent chance of actually happening, according to Greenlink Analytics, a nonprofit that promotes transitioning to clean energy.

“We believe that this is a very aggressive forecast coming from the utilities,” said Etan Gumerman, Greenlink’s director of analytics who did the modeling for the report.

Because the data center industry is growing and changing so fast, it’s hard to predict accurately. The report finds data center energy use across the region could grow by anything from 2.2 to 8.7 gigawatts by 2031. Still, rapid improvements to technology that could make AI much more efficient in the coming years are likely to dampen the overall increase in energy demand.

But electric utilities across the region are planning for the extreme high end of data center growth, the report finds. That creates a risk that utilities will build more infrastructure than data centers actually need.

“Who’s going to pay for that?” asked Gumerman. “Not the data centers that never came.” Regular customers, he said, will likely end up paying those costs. “And I think that’s the problem in a nutshell.”

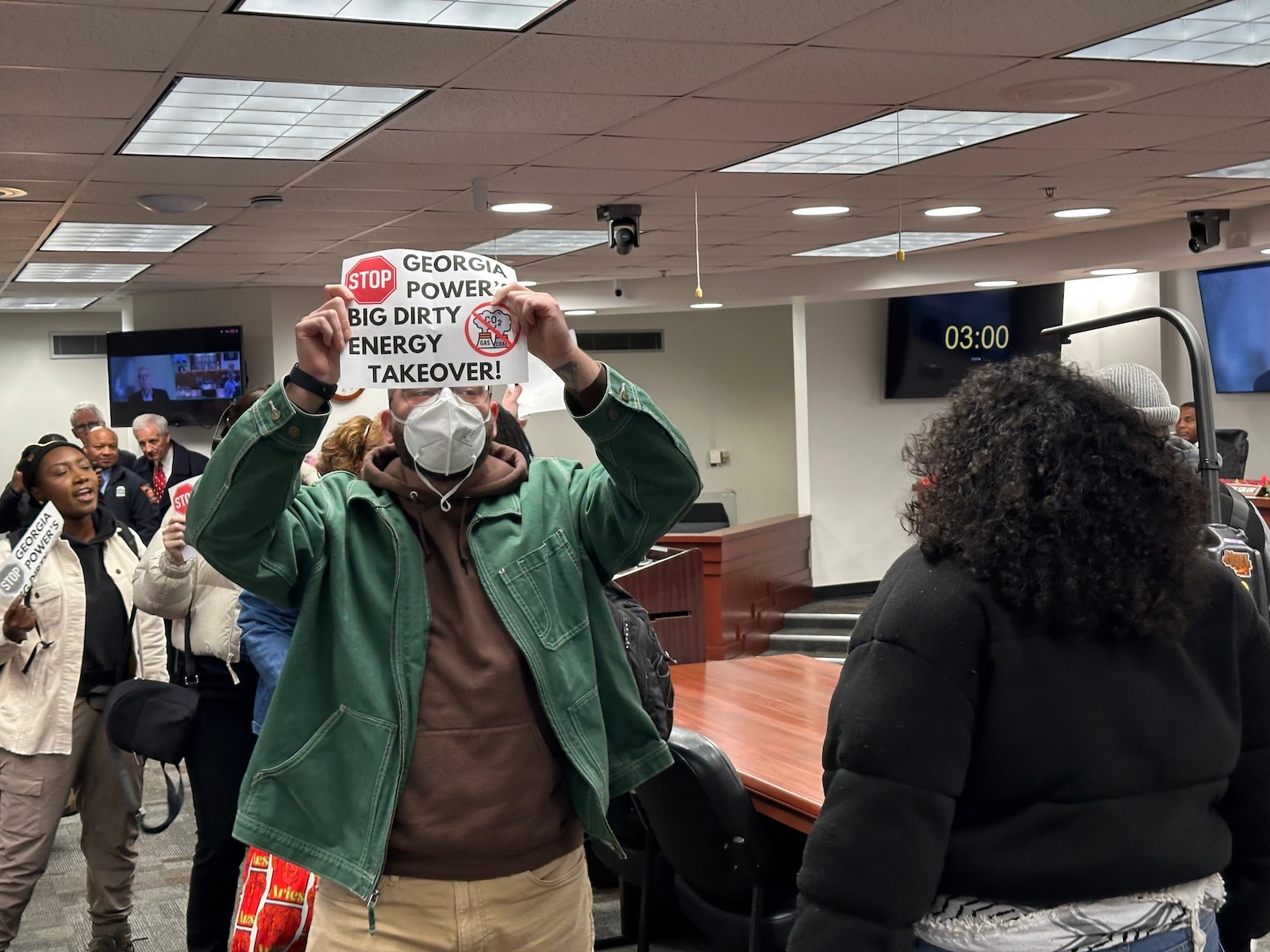

The Greenlink report is far from the first to question the projections for how much energy data centers require and how much that generation will affect individual ratepayers. Many people, from public commenters to expert consultants to the Public Service Commission’s own staff, made similar points last year during hearings over Georgia Power’s now-approved expansion. The risk of residential and small business customers paying for infrastructure built mostly for data centers was a persistent concern.

The Georgia PSC has taken several steps to protect ordinary ratepayers from data center costs. New billing terms approved last year allow Georgia Power to collect minimum payments from large power users like data centers and commit them to 15-year contracts — measures designed to ensure those customers pay for any infrastructure built to serve them and continue to pay even if they leave the state. As part of the agreement to approve the 10 gigawatt expansion last year, the utility agreed to backstop costs if the projected demand doesn’t materialize. The commission has also stressed it can still halt the recently approved projects. Clean energy and consumer advocates are skeptical these measures are enough.

In addition to the risk of rising costs for ratepayers, the sky-high demand projections for data centers are also stalling the transition away from fossil fuels as a source of electricity. Studies have found much of the coming data center demand could be met without building new infrastructure, through improving efficiency among utilities nationwide and through flexibility by the data centers themselves. Instead, utilities and data centers alike are falling back on natural gas. The U.S. now leads the world in gas-fired capacity in development, nearly tripling the total from 2024 to 2025, according to Global Energy Monitor. Much of the capacity utilities are building is to meet increased demand from data centers, and more than a third of the whopping 252 gigawatts in development is on-site power for data centers. That latter approach — where data centers are built with their own source of power, known as “behind the meter” generation — addresses the concern over rising costs but not fossil fuel emissions. While some tech companies are pursuing nuclear energy for their data centers, currently most of the power is coming from gas.

In Georgia, for instance, Georgia Power officials have said the vast majority of the projected demand driving the company’s expansion comes from data centers. The utility has already delayed plans to close coal-fired power plants and begun adding new gas-fired turbines, and the 10 gigawatt expansion approved in December will come mostly from new gas turbines, which have projected lifespans of 45 years, and natural gas-generated electricity purchased from other utilities.

“I think people would be a lot less hesitant and a lot less up in arms about these 10 gigawatts if it was sustainable, smart growth,” said Amy Sharma, executive director of Science for Georgia, a nonpartisan group advocating for the use of science in public policy. “The idea that we’re going to add this additional capacity with gas-fired turbines is horribly depressing and, as my high school daughter likes to remind me, so last century.”

The state legislature in Georgia is currently considering several bills to address data center concerns. One would ensure regular customers don’t pay for power generation built for data centers. Others would require more transparency from data center developers or even impose a statewide moratorium.

There are also bills to end the tax breaks that data centers currently receive in Georgia. State lawmakers already passed a bill to suspend tax exemptions for data centers in 2024, but Governor Brian Kemp vetoed it.