Late last year, Princeton researchers released a major study modeling different ways the U.S. could reduce its net emissions to zero by 2050 — a target that has been advanced by scientists, and countries around the world, as our best hope for limiting the worst effects of climate change. The models were designed to prioritize cost-effectiveness, and the researchers found that the U.S. could in fact achieve net-zero by 2050 without spending much more of our gross domestic product on energy than we do today. But that finding came with several caveats, including the warning that “expansive impacts on landscapes and communities” will have to be “mitigated and managed to secure broad social license.”

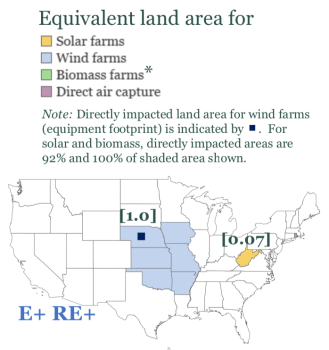

Put more bluntly, a lot more Americans are going to have to get on board with having renewable energy infrastructure like wind farms in their neighborhoods. The researchers estimate that we’ll need to devote between 93,000 and 400,000 square miles of land to wind farms in order to meet that net-zero goal. While the wind turbines’ direct footprint would only be about 1 percent of those figures, their visual footprint — the area throughout which you would likely be able to see the turbines — could be as big as Nebraska, Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Arkansas combined. The study calls “community opposition to visual and land-use impacts of wind” a “potential bottleneck deserving immediate attention.”

Under one pathway with 100% renewable electricity and aggressive electrification, wind turbines could take up an area as big as Nebraska, Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Arkansas combined. Princeton / Net Zero America study

Community opposition is already a major obstacle to the development of wind farms. Despite national polls that indicate that wind energy has broad social license to expand, local battles still slow projects down, drive up their costs, and in some cases, kill them altogether. To address this bottleneck, policymakers might turn to social scientists, who have spent decades trying to untangle the complex dynamics that go into how communities respond to these projects. Recent findings could help planners predict where wind projects might be more welcome, and where they might need to do more work (or spend more money) to earn community support.

The first thing to understand about community opposition to wind is that it’s not just a matter of NIMBYism, the idea that people might support wind energy in general but selfishly don’t want it in their backyard. “Researchers have looked into that question in particular,” said Joe Rand, a senior scientific engineering associate at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, “and said you know what, there are legitimate reasons why people are concerned. There’s meat and the bones of why there could be opposition.”

Past case studies and surveys have tied opposition to the perception within a community of unfair or nontransparent decision making, and to a lack of a clear benefit to the community for hosting the project. The implication is that opposition can be warded off or ameliorated if developers consult with communities early and often in the process and work out local “co-benefits” such as jobs, energy bill credits, investments in schools or roads, or even co-ownership.

And yet it’s not that simple. Sarah Mills, a researcher at the University of Michigan, has watched as proposed wind farms in Michigan that seemed in many ways identical — the same developer, the same permitting procedures, similar lease agreements with local landowners — were met with very different reactions. “It’s super contentious in one community and not contentious in another community,” Mills said. “My sense was that there was something underlyingly different about those places.”

She and her colleague Douglas Bessette recently investigated whether certain characteristics of a community might predict how a wind project will be received independently of developer practices and permitting processes.

“Understanding whether it’s different individuals within a community or different communities themselves … which are more willing to accept this kind of infrastructure and which are not, I think, is going to help align future policies,” Mills said.

Limiting their study to four Midwestern states — Michigan, Minnesota, Illinois, and Indiana — Bessette and Mills made a list of wind farms and asked local energy professionals to rate on a scale of 0 to 10 how contentious the project had been prior to its construction. Then they weighed those scores against a wide range of public data, including population density, political affiliation, educational attainment, the size and other characteristics of farms in the area, and the presence of scenic features on the landscape, looking for correlations.

They found that areas with more natural amenities — defined by the United States Department of Agriculture as water bodies and topographical variation — had more contentious wind farm proposals. In addition, wind projects were less contentious in communities where landowners lease their farmland to offsite farm operators instead of cultivating it themselves. These tend to be areas with more production-oriented farms — think vast expanses of big commodity crops like corn and soy — rather than part-time or hobby-oriented farms, whose operators tend to live on the property. “These ag-centric communities likely see wind development as one more way for their land to be productive,” the authors write in the study.

Past case studies had already shown that wind tends to have support in farming communities and is often viewed negatively in tourist areas, but this is the first study to collect data on a whole slew of projects — 69 total — and corroborate those observations with hard data. “Now we have statistics behind those, which I think is helpful,” said Mills.

Even more helpful will be future work that expands on this research to look at more of the U.S., something that Mills intends to do. Her study also only included wind farms that were actually built, which may have skewed the results. Next time she hopes to incorporate projects that were canceled, too.

“Work like this needs to be highlighted, and we need more work of this nature to be conducted,” said Rand, who was not involved in the study. “I really think that the social, cultural, and institutional challenges are coming to the forefront.”

Rand says that as more of the “lowest-hanging fruit” gets taken — sites with good wind that are close to transmission lines and far away from people — researchers expect projects to become more contentious. Mills’ study supports this hypothesis: It found a correlation between the year a project came online and its contention rating.

But while Mills’ study can offer developers some guidance about where they might face less resistance, Rand said it would be unrealistic to think we could only develop renewable energy in places where 100 percent of the community is on board. For him, the role of social science research is not to figure out how to avoid opposition, but rather, how to enable more responsible development that leads to better outcomes for all parties.

“That would mean developers are better equipped with tools, techniques, or approaches to work with communities to increase co-benefits,” Rand said. “Or communities themselves and their elected officials are similarly better equipped with the knowledge, tools, resources that they need to have a positive outcome when developers come knocking.”

The research could also feed into the models used in the Princeton report mapping out paths to net-zero. Erin Mayfield, a postdoctoral researcher at Princeton who worked on the land use and renewables siting aspects of the report, pointed out that she and her fellow researchers were optimizing for cost, but the cheapest way to decarbonize isn’t necessarily the best or most realistic one. In future research, she said, they plan to integrate other constraints and objectives such as community preferences and balancing the costs and benefits to communities, using social science research.

“Modeling has often been a very kind of a technocratic approach,” she said, “but it’s not how systems actually develop. It’s not reflective of what people care about, both now and potentially in the future. Without incorporating these other objectives … we are losing a big part of the picture, and it’s not reflecting what could happen or what we may want to happen.”