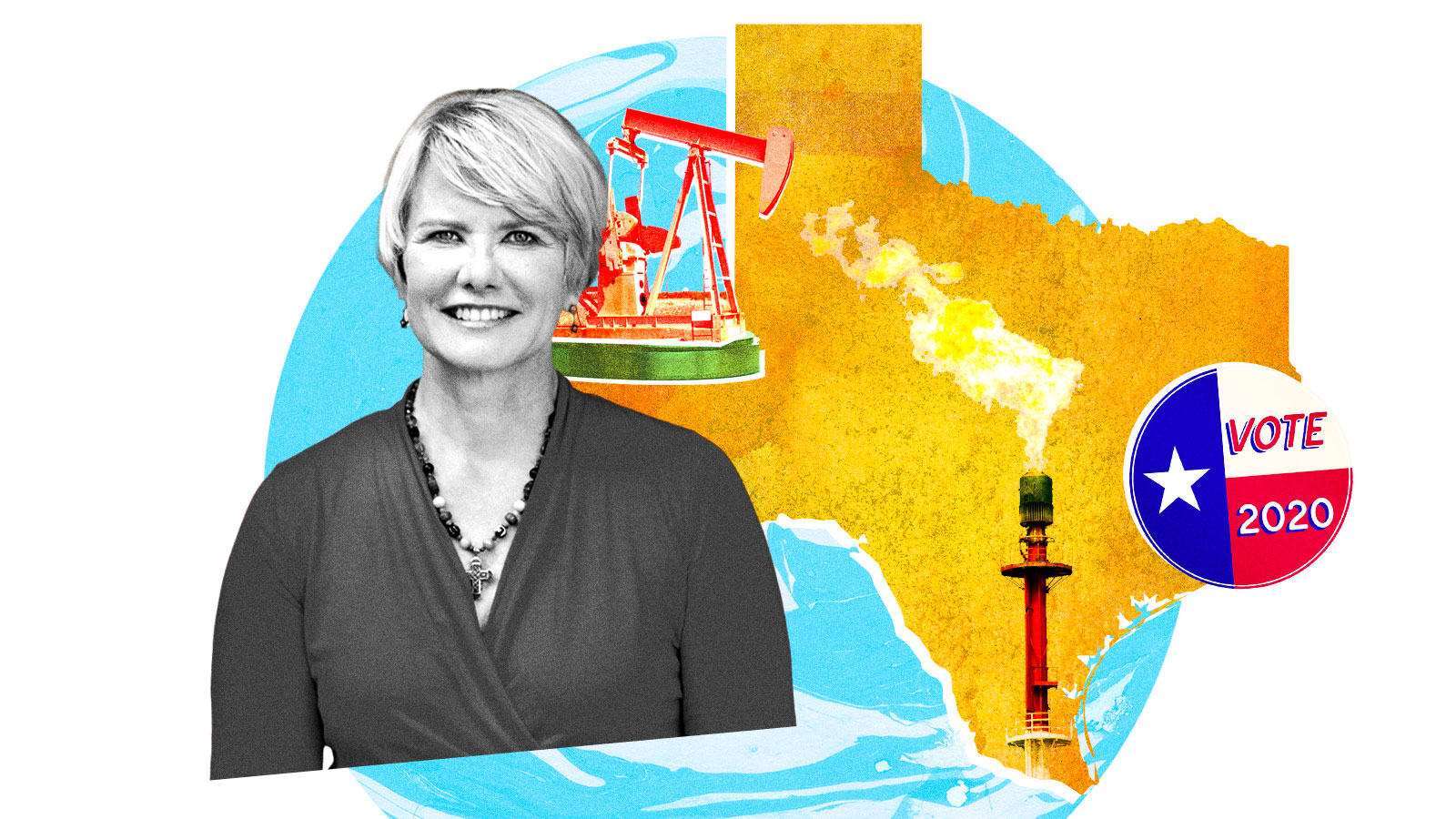

Oil and gas companies burn off billions of cubic feet of natural gas into the atmosphere every year in Texas alone. It’s both wasteful — the gas could be used to power the state’s populous cities many times over — and a major source of climate-warming pollution. Nevertheless, the Texas Railroad Commission, the state agency that regulates the industry, has largely sanctioned the practice, rubber-stamping applications from companies that want to engage in unlimited flaring.

An under-the-radar election for one of the commission’s three seats could change all that. On November 3, Democrat Chrysta Castañeda will face off against Republican Jim Wright, a South Texas businessman who runs an oilfield waste and recycling company. The odds are stacked against Castañeda: She’s running for a position that a Democrat hasn’t won in three decades. But with Democrats suddenly polling competitively up and down the ballot in Texas — not to mention a recent $2.6 million donation Castañeda’s campaign received from former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg — the oil and gas attorney from Dallas may have a fighting chance.

If she wins, she may be in a position to get the commission to drastically reduce greenhouse gas emissions in some of the largest oilfields in the country. For this reason, she calls the race “the most important climate election in the nation.”

Political analysts agree that the contest may be getting less attention than it deserves.

“This is a sleeper race,” said Brandon Rottinghaus, a political science professor at the University of Houston. “If there’s a statewide race [in Texas] that Democrats might win that is not on people’s radar, then it’s this one.”

For one, Castañeda is not facing an incumbent. Wright, her opponent, pulled off a stunning upset against an incumbent commissioner in the Republican primary, causing some to speculate that his name may have reminded voters of the former Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives Jim Wright, who died in 2015.

The Republican nominee has also been found in violation of state environmental and permitting rules more than 250 times by the very agency that he hopes to join. The Railroad Commission also fined him more than $180,000 in 2017, and he is battling a series of lawsuits that accuse him of fraud. (Wright’s campaign declined to provide Grist any comments for publication.)

Despite its yawn-inducing name, the Railroad Commission is a powerful state agency that regulates the coal, oil, and gas industries. It approves permits for fracking, signs off on pipeline routes, grants companies the power of eminent domain, and oversees coal mining and cleanup. In a state that’s heavily dependent on oil and gas extraction to power state and local budgets, it has tremendous influence on the economy. The agency is governed by three commissioners who are elected to six-year terms. A Democrat has not served on the commission since 1994.

Over the last few years, the agency has faced increasing scrutiny of its regulation of flaring — an industry term for burning off excess natural gas when pipelines are already at capacity, or when that gas is deemed unworthy of the cost it takes to send it to refineries. The commission sets limits on flaring, but it also routinely grants long-term exemptions to operators who request one. The agency has granted more than 12,000 such exemptions over the past two years, allowing oil and gas companies to burn hundreds of millions of cubic feet of natural gas. That’s up from around 300 in 2010.

Even major oil and gas companies have called flaring a “black eye” for the industry’s image. Most people don’t want to live near flares, which are both unsightly and an obvious source of pollution. For oil behemoths like ExxonMobil and BP, which have pledged to cut down their carbon emissions, flaring is low-hanging fruit.

Under pressure from major oil and gas companies as well as environmental groups, the Railroad Commission took up changes to flaring regulations earlier this year. It proposed requiring companies to provide additional data about the volume of gas to be flared and the exact location of flares. It also requires companies to detail plans for flaring reductions, but it doesn’t set hard limits on how much companies can burn.

Castañeda said that these rules are meager and “would have been a great information-gathering exercise five years ago.” Instead, she says, the commission should use the authority it already has to reject applications for exemptions, and it should push the industry to deploy alternative technologies that reduce flaring.

“It has become routine practice to flare rather than to capture the energy — and that violates the bedrock principle of the Railroad Commission, which is to preserve our natural resources,” she said.

Industry players have primarily lined up behind her Republican opponent. Wright has secured the endorsement of the Texas Oil and Gas Association, as well as current railroad commissioners Christi Craddick and Wayne Christian. When it comes to flaring, Wright acknowledges the problems the practice poses but posits that the solution is to build additional pipeline capacity to move natural gas to refineries.

“Flaring is just that – waste,” he says in a position paper on his website. “The need for more transport capacity is apparent and any barriers to building out that capacity should be removed.”

The contrast between the candidates on the issue of climate change more broadly is stark. Wright has said that he’s not sure “we have good facts on what’s causing our climate change,” while Castañeda says that climate change is real and human-caused. Still, the Democrat says it’s possible to balance “responsible” oil and gas extraction and reduce greenhouse gas emissions “all at the same time.” (Scientists say that most fossil fuels need to be left in the ground in order to avoid catastrophic climate change.)

Rottitnghaus said that Castañeda’s positioning is strategic and “probably wise.” She is running in Texas, after all. “It’s a safer political choice,” he said. “If you start talking about fracking and bans on fracking, that opens you up to all kinds of different political problems that other Democrats have faced from Republican challengers.”

Castañeda has represented oil and gas companies in her work as an attorney, and she made headlines when she secured $146 million in damages for T. Boone Pickens, the Dallas oil tycoon, in 2016. She told Grist that she is not currently working with any operators involved in oil and gas extraction, and that she is rejecting new case work at least until election results are in.

If elected, Castañeda may be able to push the commission to approve stricter flaring regulations. The commission requires a majority vote for proposals to pass. Companies’ requests for flaring exemptions are also put to a vote. Given that the other two commissioners have expressed interest in strengthening flaring regulations, Castañeda may find allies. The chair of the commission, Wayne Christian, set up a “Blue Ribbon Taskforce” to tackle flaring earlier this year. The practice, he said, is “tarnish[ing] the reputation of our state.” Many of the task force’s recommendations have found their way into the proposal the agency is now considering passing.

As for consensus-building on the commission, Castañeda believes that there is widespread buy-in for finding solutions that address rampant flaring.

“What’s missing is the political will to help the people who follow the law to follow the law — and not benefit those who are disregarding the law by giving them an unfair economic advantage,” she said.

Castañeda hopes to bring that political will if she wins next week.