This story is published in collaboration with BridgeDetroit.

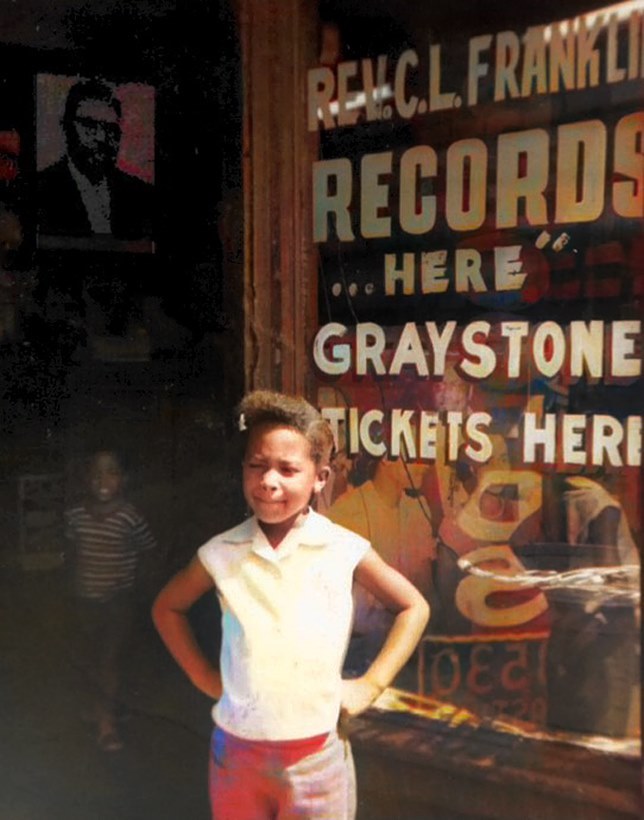

In 1945 in Detroit, Michigan, a man who is believed to be the first African-American independent record producer opened up a blues and gospel record store called Joe’s Record Shop. The store was lined with vinyl records and music posters, with a big, upright piano in the back. Joe Von Battle started the business by selling records from his personal collection. Later, he remodeled the store to include a recording studio. His shop was a focal point for the music scene on Hastings Street — the center of Black business and entertainment in 1950s Detroit.

“People sang up and down the street, they played their guitars on the corner, they sang gospel,” said Von Battle’s daughter, 67-year-old Marsha Philpot, more commonly known as writer Marsha Music, “so my dad began to record these people.”

Von Battle recorded blues artists like John Lee Hooker and was the first person to ever record Aretha Franklin. At one point, Joe’s Record Shop had 35,000 albums in its inventory and generated the present-day equivalent of $2.5 million in revenue. “My father had been very, very successful in his record business,” Music said.

But in 1960, Von Battle was forced to close his shop and relocate to make way for I-375 — a giant, four-lane sunken freeway. Over a mile of Hastings Street and its surrounding land was turned over to developers, dismantling the once thriving epicenter of Black life in Detroit in order to create a high-speed thoroughfare from downtown to the surrounding suburbs. Hastings Street was home to more than 300 Black-owned businesses, including restaurants, doctors’ offices, and even eight grocery stores. Hundreds were forced to relocate or close permanently. Today, there isn’t a single Black-owned grocery store in Detroit, the Blackest big city in America.

After his building was demolished, Von Battle moved his record shop from the east side of Detroit to the west side, on 12th Street. The business struggled. Von Battle battled alcoholism and was soon diagnosed with Addison’s disease. Eventually, he permanently closed the shop after it was destroyed in Detroit’s 1967 race riots. Music and her siblings believe the shop’s forced displacement from Hastings Street was likely the catalyst for their father’s alcoholism. “He was very despondent,” Music told Grist, describing on her website that he “drank himself to death.”

In June 1956, President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the Federal Interstate Highway Act into law, spurring a multi-decade national infrastructure building boom. In cities across the U.S., these new roadways were disproportionately routed through communities of color. From Detroit to New Orleans to Miami, this construction helped contribute to the decimation of the culture, political power, and economies of Black America amidst the peak of the Civil Rights movement.

“Throughout the country, urban freeways were routed through Black neighborhoods, resulting in the malicious division and forced displacement of Black neighborhoods, as well as local Black economies,” said Regan Patterson, an environmental engineer and current fellow at the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation.

But this infrastructure is hitting the end of its lifespan, and communities are now debating what to do with their legacy highways. In Charleston, South Carolina, officials decided to double down, spending $3 billion to widen a freeway through predominantly Black and brown neighborhoods. Others, however, are questioning whether to remove them altogether, righting some of the wrongs done when communities were bifurcated so many years ago.

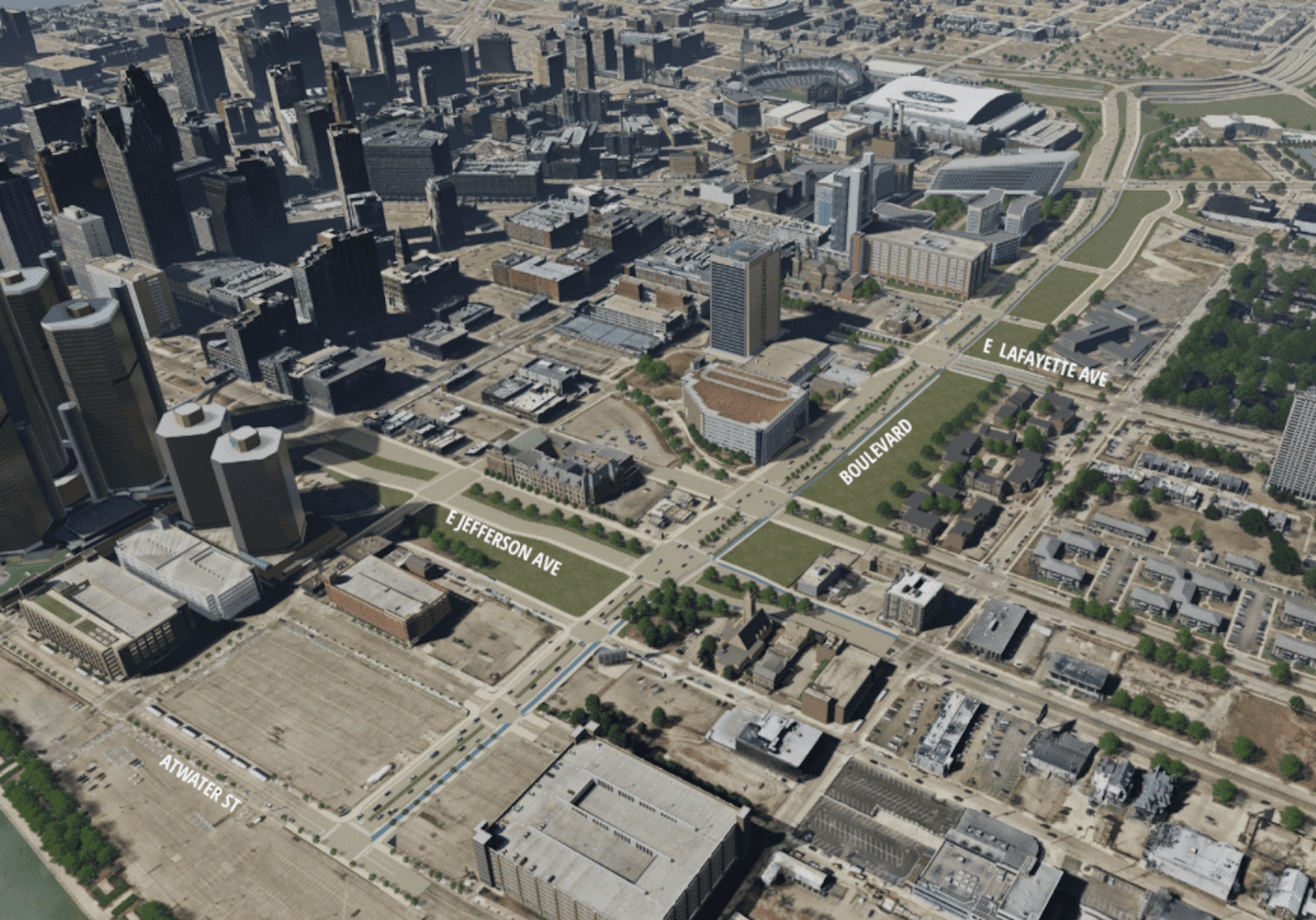

Detroit has chosen the latter. Rather than rebuild or repair I-375’s aging bridges, the Michigan Department of Transportation, or MDOT, announced in 2017 that it would replace the sunken, four-lane highway with a street-level boulevard lined with sidewalks and bike lanes. The initiative, called the I-375 Improvement Project, would reconnect the local neighborhoods along where Hastings Street once stood, as well as create a thoroughfare from Detroit’s downtown to two of its biggest cultural hubs: the RiverWalk area and Eastern Market, the largest historic public market in the country.

Detroit joins the ranks of cities including San Francisco, Seattle, Milwaukee, and Boston in choosing to remove problematic roadways. Even more cities could soon follow suit.

Earlier this month, Congress passed the long-awaited bipartisan infrastructure bill. It includes $1 billion slotted for removing roads, bridges, and highways that cut through communities of color like Hastings Street.

Detroit’s Monroe Street bridge provides a good look at I-375 in both directions. Here, the freeway spans 350 feet wide, with grassy banks on either side sloping down to the sunken concrete roadway. A barrier separates the north and southbound lanes. Monroe Street is one of 14 vehicular bridges that stretch across the 1-mile length of I-375, all of which will be taken out when the highway is removed, explained Jonathan Loree, a senior project manager for MDOT. He is standing on the bridge, looking through a chain-link fence onto the highway below. It is a warm early summer morning.

Today, the area around I-375 contains almost no trace of its historic roots. The highway is surrounded by parking garages, churches, and office buildings. Cracked sidewalks line nearby streets, but go largely unused. A juvenile detention facility and a casino sit just one block away. There are a few small apartment buildings, but otherwise no residential amenities like restaurants or stores.

The I-375 Improvement Project is expected to cost around $270 million. Officials have a target start date of 2027, but they say it will likely get underway even sooner. Federal funds are expected to cover 80 percent of the project’s budget, with the state contributing the other 20 percent. Detroit itself will pay for the construction of city streets that need to be rebuilt to fit into the new at-grade boulevard’s design. So far, the Michigan Department of Transportation has submitted a preferred design for the boulevard and a draft environmental assessment, as well as held a public hearing for community input. Transit officials expect final approval of the project from the Federal Highway Administration in December.

The new road will be six lanes and transition to four in the last portion of the boulevard, closest to the river. It will be lined by protected bike lanes and more sidewalks, measuring 22 feet across, that will double as gathering spaces. It will also open up about 12 acres of land to be used for housing, retail, or green space — details that will be determined in the next phase of the project.

For decades, the expressway interchange fractured Detroit’s walking and bike routes, making it almost impossible to travel safely in that part of the city without a motorized vehicle, Todd Scott, executive director of the Detroit Greenways Coalition, told Grist.

“It just changes everything,” he said. “It really connects the downtown to the surrounding area. If it’s filled with local businesses and multi-use, maybe it could make a lot more walkable destinations for folks who live nearby.”

Bonnie Leone has been a member of Holy Family Church, which sits just off of I-375, for more than two decades. She’s attended several community meetings for the project in the last few years. “We see it as kind of putting the neighborhood back together,” she said.

Loree and community advocates say there’s also potential to incorporate stormwater infrastructure in the boulevard’s design, something that Detroit desperately needs. The city’s many sunken highways are susceptible to flash flooding, which can leave people stranded in their cars. Currently, water from I-375 goes into the city’s combined sewer system, which is easily overwhelmed during intense rainfall. When the system is overloaded, homes flood and raw sewage is released into waterways. The newly designed boulevard, and its more direct connection to the riverfront, could help manage excess water both today and under future climate scenarios, Loree said.

While the I-375 Improvement Project will have a lot of benefits, can it ever recover what was lost by the highway’s creation in the 1960s? And how can it protect current residents against gentrification?

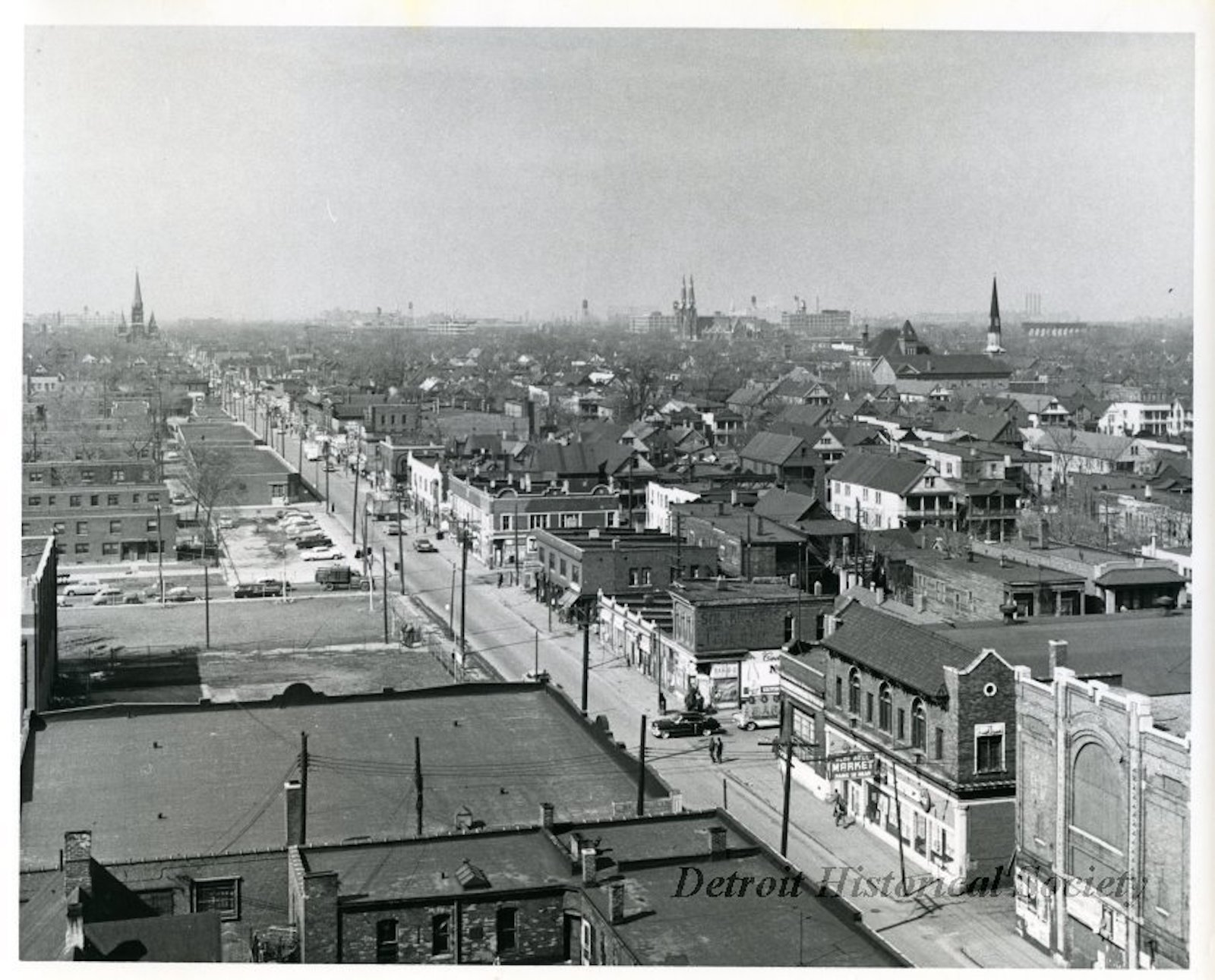

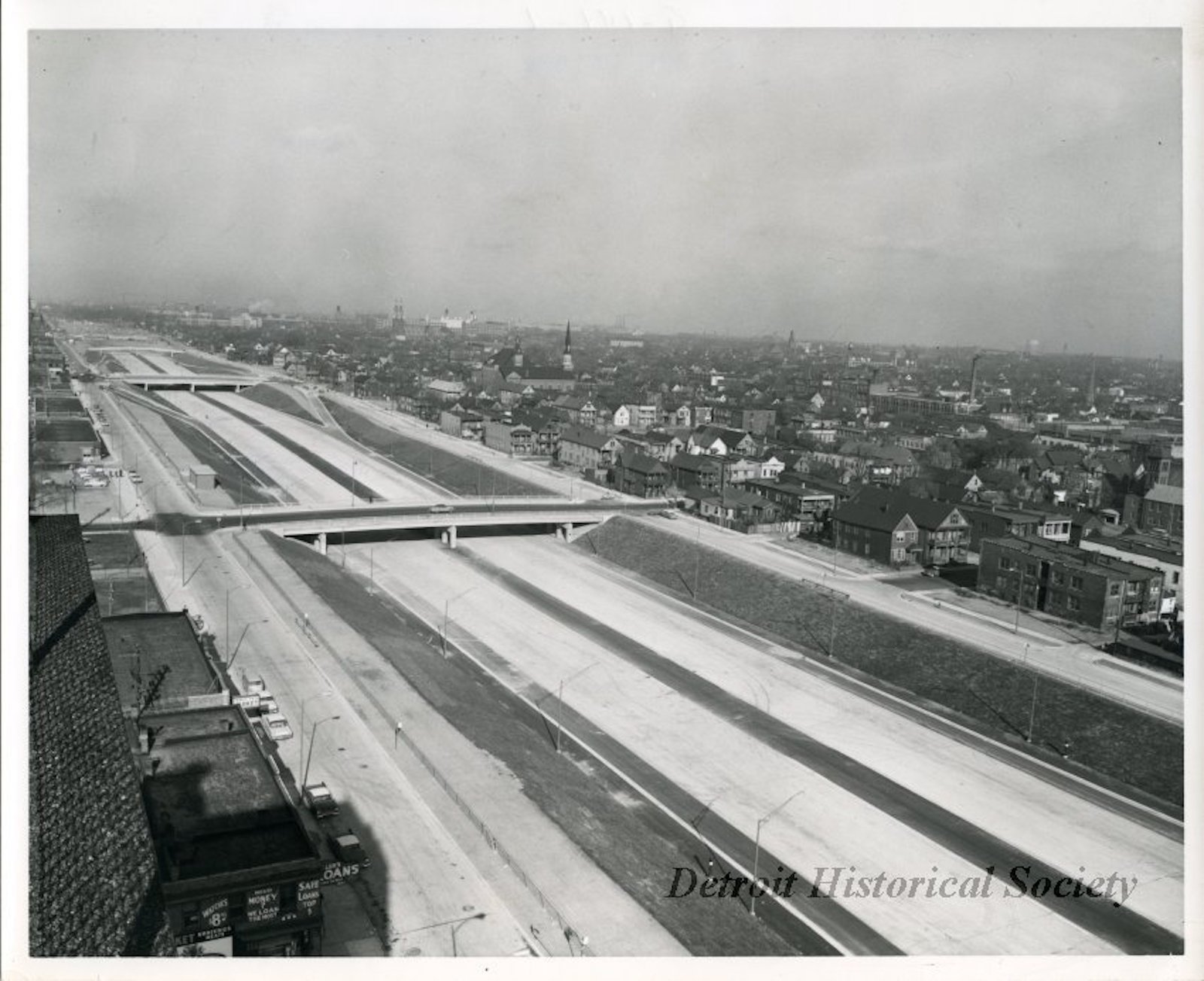

An aerial view of Hastings Street looking north from Mack and St. Antoine in 1959 (left) and then after the construction of I-375 in 1961. Images courtesy of Detroit Historical Society

Hastings Street ran north-south through Detroit’s Black Bottom neighborhood and Black entertainment and business district, known as Paradise Valley. The destruction of the epicenters of Detroit’s Black life started with the condemnation of housing through the National Housing Act of 1949, which gave money to cities for “slum clearance and urban revitalization.” (Public policy had long restricted Black people to living in the worst, cramped housing in the city.) It continued when the city received even more funds through the National Highway Act in 1956.

“Highways increased air pollution, increased noise pollution, and forced displacement,” said Patterson.

It’s unknown just how much intergenerational wealth was lost from the construction of I-375 in Detroit. What would have happened if Joe’s Record Shop or the hundreds of other businesses that lined Hastings Street had been left alone? Where would those families be now? Comparison to a similar event in another city may offer a clue.

In Minnesota, a highway was built in the 1950s and 60s through Rondo, a thriving African-American cultural center in St. Paul, displacing 700 homes and 300 businesses. The neighborhood’s population decreased by 61 percent, and homeownership declined by 48 percent. Had Rondo followed the home value trends of St. Paul more broadly, an additional $270 million of intergenerational wealth would have existed for Black families today, according to an analysis by Yorth Group, an infrastructure advisory firm for the community nonprofit ReConnect Rondo. And that’s likely an underestimate, as the analysis focused only on the homes lost by the project, not the 300 businesses also destroyed.

Keith Baker, a transportation equity expert and executive director of ReConnect Rondo, says the significance extends to what that money could have been used for in the 1980s had those houses been sold or accumulated value. “Home equity was often used to provide educational opportunities for children,” he said. “We all understand the economic benefit of higher education or training and what it means to the health and well being of a community.” At that point in history, Baker estimates 3,400 college degrees could have been paid for with the housing profit that was lost when the homes were destroyed.

“It’s something that no one ever quantifies when you think about what’s lost,” said Lauren Hood, chair of the Detroit Planning Commission, an advisory committee that gives recommendations to the City Council on development in the city. Hood is a Detroit reparations fellow through the University of Michigan, a role in which she’s looking at exactly what was lost from the destruction of the Hastings Street neighborhoods of Black Bottom and Paradise Valley, and what reparations for that harm should look like. It’s not just about money, she said. “We lost our community connections, our political power, so much more than just the intergenerational wealth, businesses, and homes.”

So how does this all get done? How do you tear down a highway and restore the fabric of a community? First and foremost, experts say, community participation from the beginning is key. After that, there are a number of strategies that experts say can and should be utilized to minimize harm and maximize repair.

When highways are removed and replaced, more green space, cleaner air, and decreased noise can make the space highly desirable to developers, which can displace current residents. There are different ways to prevent that from happening, though, if a city is serious about addressing the economic, cultural, and public health harm caused by the highway.

“You need comprehensive and intersectional policy solutions,” said Patterson. “They must be coupled with anti-displacement strategies to ensure that the communities that are meant to benefit [from] freeway removal initiatives actually are able to remain in the area to see these benefits.”

John Roach, director of media relations for the city of Detroit, told Grist that because the I-375 removal hasn’t been granted final approval, the city hasn’t had these discussions yet, but that it always aims to bolster affordable housing with new development.

Some Detroit residents, however, are skeptical. Music, a lifelong Detroiter, has had mixed feelings about the planning process for I-375 so far: “I always had the feeling that they were going through this dog and pony show, when they know what they’re gonna do anyway.”

Bert Dearing Jr., owner of Bert’s Market Place in the Eastern Market neighborhood, grew up just a few blocks from Hastings St. As a paperboy, his route crossed the historic thoroughfare each day. And he recalls visiting Hastings St. for most things: the movies, the barbershop, bookstores, and his grandfather’s grocery store on the corner. When they put I-375 in, “it just took the wind out of everything,” he said. Dearing told Grist he’s not convinced the highway removal will ever happen — he’s watched project after project in Detroit lose funding or never get completed. And he definitely doesn’t think the project will bring back the spirit of Hastings St. “That ain’t going to happen,” he said.

Others have critiqued the new boulevard’s physical design. The current proposal for the six-lane road to replace I-375 will encourage speeding and a higher volume of traffic — basically replicating the effects of a highway, argues Ben Crowther, manager of the Highways to Boulevards program at the nonprofit Congress for the New Urbanism. “You don’t reap the full benefits of removal if you just build another wide road,” he told Grist. A common misconception, he added, is that highway replacements must be able to accommodate the same volume of traffic, but that isn’t true: People take alternative routes, bike, walk, or skip the trip altogether if the original highway is no longer available.

A model example of community engagement that experts point to is in Minneapolis, Minnesota, where the city has created a Freeway Remediation policy that states the city will “repurpose space taken by construction of the interstate highway system and use it to reconnect neighborhoods and provide needed housing, employment, green space, clean energy, and other amenities consistent with city goals.” In addition to action steps to identify and consider areas for highway removal and land bridges, the policy includes a step to consider how profit from private development could be paid to people or descendants of those whose homes were taken by eminent domain.

Another example is I-980, a freeway in Oakland, California, that displaced over 500 homes when it was built in the 1960s. For years, activists have been working to get the freeway replaced with a boulevard. In 2019, the city proposed a plan to assess the long-term feasibility of replacing the freeway, including “using the revenues from public land to repair inequities caused by the creation of I-980.” Oakland anticipates adopting the plan by the end of 2021.

Cities can also work with community land banks or trusts to avoid displacement. A community land trust is a nonprofit organization that stewards land for nearby neighborhoods, in order to accomplish goals like securing affordable housing. A family enters into a long-term renewable lease instead of buying the home. Then, if they decide to “sell,” the family earns a portion of the home sale, and the rest is kept by the trust to ensure affordability for future families. A land bank, on the other hand, holds abandoned land for future development until the community knows what it wants to do with it and transfers ownership. Because the I-375 removal is still in the proposal phase, the city of Detroit has not planned which — if any — of these strategies it will use.

These techniques have been well-tested. In Washington, D.C., the nonprofit Building Bridges Across the River is developing a park over an abandoned bridge, linking the upscale neighborhood of Capitol Hill with Anacostia, a low-income and predominantly Black community. To prevent gentrification, the nonprofit launched the Douglass Community Land Trust, which is ensuring that 200 units of housing stay affordable in perpetuity. Additionally, Building Bridges worked with MANNA, another nonprofit, to create a home-buyers club. So far, 87 renters in the area have become homeowners through the program.

Inclusionary zoning is another option. Through these programs, developers are required or incentivized to offer a certain number of units in new projects at lower prices. Developers often sign on because it can mean they’re allowed to develop larger buildings than existing zoning allows. But, the research on how effective this private affordable housing strategy is generally unclear. Inclusionary zoning typically results in just a few affordable units, leaving thousands of qualified candidates without affordable options and failing to ensure a neighborhood is integrated by race and income.

Even though these strategies are flawed, without them, there’s a chance highway removal can do more harm than good to communities of color, experts warn.

Baker at ReConnect Rondo said doing the intergenerational wealth analysis has been immensely helpful. “Quantifying it creates an opportunity for communities to rally around an expectation, because now they can say, ‘This was our loss.” Otherwise, he said, it’s anecdotal. “We have got to make sure that we’re speaking the language of the institutions, and that we’re translating that in a way that they fully understand the economic impact.”

After President Biden revealed his infrastructure plan earlier this year, several congressional leaders sponsored a bill that would put Biden’s promises into action, called the Reconnecting Communities Act. The program would address the “legacy of highway construction built through communities, especially through low-income communities and communities of color, that divided neighborhoods and erected barriers to mobility and opportunity.” Originally, the proposal included $20 billion for highway removal, but that was cut to $1 billion when it was folded into the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act passed by Congress last month.

The program includes community engagement grants for government agencies and nonprofit organizations to work with residents to see what they want out of highway removal. And there’s proposed funding for community land trusts, Patterson says, “to ensure that the community is still empowered in terms of land decisions.”

“It’s just that recognition of process,” she said, praising the act for acknowledging that freeway removal itself isn’t a solution — it requires intentional community involvement as well.

MDOT is hoping to get some of the infrastructure bill money for Detroit, in which case it could bring the timeline of the I-375 removal project forward, Loree said. Once the boulevard proposal is approved by the Federal Highway Administration, I-375 would be de-designated from the Interstate System of Highways. Then, MDOT would conduct the final, permanent design phase, which includes local stakeholder feedback and engagement. Construction would begin in 2027, if not sooner. One option for the new name of the boulevard is “Hastings Street.”

Because of the loss of her dad’s record store, Music says people always want to know what she thinks about Detroit’s highway and the removal project. “Because I understand the gravity of the destruction that took place and I understand it personally, it’s hard to be very sanguine about anything that’s going on now,” she said.

“An entire generation of wealth has been eliminated, people’s businesses have been altered. Now, it’s like ‘Oops, maybe we shouldn’t have done that,’” Music said. “It’s hard to feel jubilant about that, even if it is a potentially progressive move.”

This story has been updated to reflect Marsha Battle Philpot’s more commonly used name, Marsha Music.