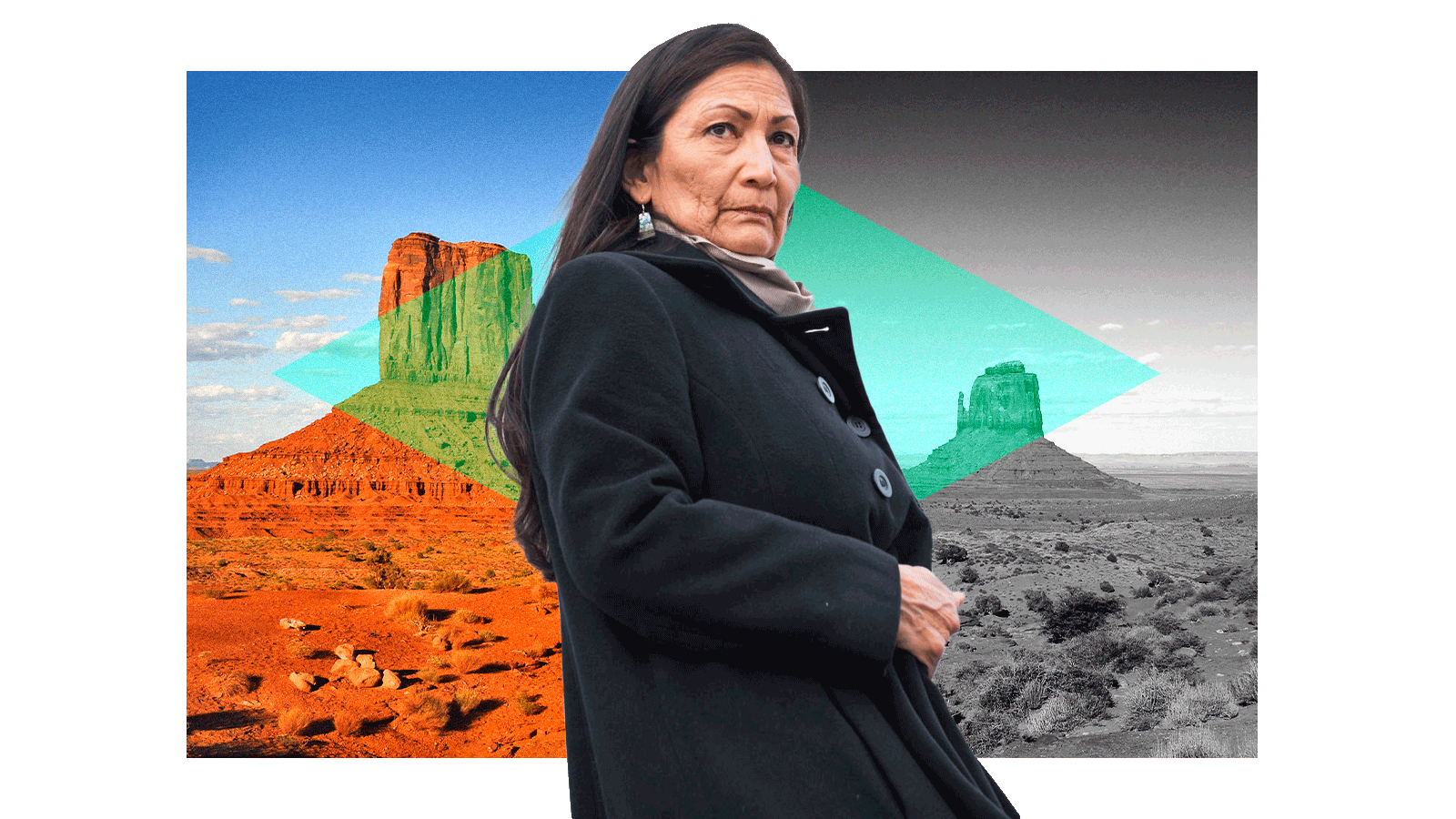

Newly appointed Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland has pledged to address the concerns of U.S. communities that have disproportionately suffered from pollution and environmental degradation. In her role as the primary steward of America’s public lands, Haaland promised last week to incorporate diverse perspectives and prioritize environmental justice across the agencies of the Department of the Interior. In a secretarial order announced on Friday, the secretary said that these approaches would be integral to the department’s renewed focus on climate change.

In an interview with Grist ahead of the announcement last week, Haaland, who is the first Native American in U.S. history to serve as a cabinet secretary, said that her approach is part of President Joe Biden’s broader goal to ensure that the federal government works to address environmental justice every day. Haaland said that part of this is making sure that vulnerable communities experiencing environmental disparities are heard and helped.

“For generations we’ve put off the transition to clean energy, and now we face a climate crisis,” Haaland, a 35th generation New Mexican and member of the Pueblo of Laguna, told Grist. “It has fallen on those communities: communities of color, poor communities. You can bet that I’m going to do everything I can to help those communities to have an opportunity to build back better.”

The Department of the Interior oversees the Bureau of Indian Education as well as the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and their work intersects with the lives and interests of about 1.9 million Indigenous peoples and 574 federally recognized tribes across the country.

Alongside issuing the new secretarial order, Haaland also revoked a series of orders issued under the Trump Administration. Among the dozen orders revoked are an order canceling an Obama-era federal coal leasing moratorium, an order to promote development of the National Petroleum Reserve in Alaska, and an order that established an executive committee to expedite energy-related permitting. She said that these previous orders are inconsistent with the Biden administration’s commitment to protect public health, conserve the environment and wildlife, and elevate science.

“Those previous orders unfairly tilted the balance of public land and ocean management toward extractive uses without regard for climate change, equity, or community engagement,” Haaland said during a video announcement.

As a U.S. representative from New Mexico, a position where she also made history as one of the first Native American women elected to Congress, Haaland likewise prioritized environmental justice, conservation, and climate change. In the House of Representatives, where she served as vice chair of the Committee on Natural Resources and chair of the Subcommittee on National Parks, Forests, and Public Lands, she co-sponsored the 2020 Environmental Justice for All Act, which was recently re-introduced in Congress.

Last year, at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, Haaland argued for the need to address long-standing health disparities in communities of color that are caused by exposure to environmental pollution. During a congressional roundtable on environmental justice, economic inequality, and the COVID-19 response in April, she noted that pollution from uranium mining has contributed to underlying health conditions such as respiratory illnesses, which in turn has made Native American communities more vulnerable to the coronavirus. At the time, Native Americans represented 47 percent of the positive coronavirus cases in New Mexico, despite being just 11 percent of the state’s population. The underfunding of agencies such as the Indian Health Service, established to provide health care to Native Americans, she said, has led to substandard care and made access to health care a challenge.

“These conditions are mirrored across the other environmental justice communities as we try to deal with this pandemic, and it’s costing our people and their parents and grandparents their lives,” Haaland said during the roundtable.

Haaland told Grist that President Biden has made tribal consultation a priority in his administration — and not just with the Bureau of Indian Affairs under the Department of the Interior, but across all federal agencies. She said that as the pandemic exposed disparities such as the lack of access to clean water within the Navajo Nation, it also made clear that only a cross-agency approach could begin to improve conditions in disadvantaged communities.

“I’m happy and grateful that that is our charge: to make sure that the folks who are suffering those environmental injustices have an opportunity to talk about it and be heard,” said Haaland.

Having an Interior Secretary who is willing to listen to the environmental concerns of the nation’s tribes is crucial for those who are already working on the ground to clean up Indigenous lands contaminated by uranium mining, said Dariel Yazzie, environmental assistant director for the Navajo Nation Environmental Protection Agency. He cited Haaland’s knowledge of Laguna Pueblo’s Jackpile-Paguate Mine in New Mexico and her understanding of the lengthy cleanup process there as one reason why her appointment could be a game-changer.

“I know the struggles are what she would understand, what she would relate to,” said Yazzie. “And having her in a position to help us identify pathways to move us forward, with her support, would be ideal.”

Indeed, during her confirmation hearing, Haaland said that more resources are needed to clean up abandoned uranium mines, and she specifically cited the Navajo Nation’s water pollution issues. Thirty million tons of uranium ore were extracted for atomic weapons and power during mining operations that began within the Navajo Nation in 1944 and halted in 1986. Eighty years later, the legacy of more than 520 abandoned uranium mine sites continues to haunt the Navajo Nation as slow-moving cleanup efforts means that Navajo residents continue to live with environmental hazards that place them at risk for diseases such as lung cancer, renal failure, and respiratory diseases, said Yazzie.

“We knew the U.S. government was aware of what these health implications were, yet we’re still sitting here with them after 80 years,” added Yazzie, whose family hails from Cane Valley, Arizona, where he grew up near a mining site and experienced those health effects personally. His father worked as a uranium miner and has experienced both lung and heart disease.

Various federal work plans created to aid the cleanup efforts have failed to initiate the removal or remediation of many of these mining sites, according to Yazzie, leaving communities exposed to the hazards of contaminated soil, water, and air. “Eighty years is too long for anybody to live in these conditions where these issues still exist,” he said.

Haaland said that tribal consultations with the Department of the Interior are already underway on matters like the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, which provides emergency supplemental funding directly to tribes to address the effects of COVID-19. The consultations were organized immediately after the act’s passage to, as Haaland put it, “meet with tribes as they are.”

“My family, my grandparents, my ancestors: They lived with decisions that were made by this department and by the federal government in the past without ever having an opportunity to raise their hand or have a seat at the table,” said Haaland. “We want to give [tribes] a seat at the table for issues… where they can help us to make the right decision.”

Haaland plans to bring this close listening approach to decisions around oil and gas drilling on public lands. “Every single taxpayer in this country deserves a fair return on anything that any industry is doing with our public land,” she said. “We need a balance on our public lands.”

The need to strike that balance is keenly felt by those who hail from Haaland’s home state. On Wednesday, during a press conference on the health, climate, and social impacts of the federal government’s oil and gas leasing program in New Mexico, community advocates discussed the consequences of unchecked drilling that local communities are most concerned about, including the health impacts of pollution. (Wednesday was the final day that the Department of Interior was accepting public comments in response to a review of the federal oil and gas program.)

Earlier this year, the Biden Administration announced that it would pause new oil and natural gas leasing on public lands and offshore waters, and it directed the Department of the Interior to conduct a review of the federal oil and gas program. In addition, Biden directed the Interior Department to identify steps to accelerate the development of renewable energy on public lands. A statement issued by the department noted that the review would examine the oil and gas program to ensure it serves the public interest, noting that recent attempts in Congress to reform the “outdated program” have tried to ensure the public is not shut out of land management and leasing decisions.

“Fossil fuel extraction on public lands accounts for nearly a quarter of all U.S. greenhouse gas emissions. Irresponsible leasing of public lands and waters impacts communities’ access to clean air, clean water, and outdoor recreation; carves up important wildlife habitat; and threatens cultural and sacred sites,” the department stated.

For Mario Atencio, an at-large board member of Diné C.A.R.E. (Citizens Against Ruining the Environment) who spoke at Wednesday’s press conference, this assessment couldn’t come soon enough. For more than three decades, the community-based organization has defended Navajo communities against polluting industries, preventing the siting of a medical waste incinerator as well as an asbesto dump, among other efforts. Atencio has seen firsthand how fallout from the oil and gas industry’s extractive processes harm the surrounding land.

During the virtual press call, he described how a February 2019 spill near his grandmother’s house in Sandoval County, New Mexico, has yet to be comprehensively addressed. Nearly 59,000 gallons of fracking slurry mixed with crude oil leaked off a well site owned by a Denver-based company. Three days later, an explosion occurred at a nearby well site owned by the same company. An investigation by the news nonprofit Capital & Main found that, since those incidents, there have been an additional 317 accidents in northwestern New Mexico, ranging from oil spills to fires, as well as blowouts and gas releases. In all, the report found that there have been 3,600 oil and gas spills throughout the past decade.

“There’s no discussion about holding operators accountable when they spill,” Atencio said during the press call.

Ultimately, Haaland said that her department will be guided and informed by these community perspectives, as well as data and science. She praised the breadth of expertise of scientists within the department, including career employees who have studied the effects of climate change on species and the environment.

“I want to make sure that we are following the science, that we’re empowering our scientists, to make sure we have all the available data,” said Haaland. “It’s imperative during this climate change era that we are experiencing. Every single decision that we make today is going to impact generations to come. So we have to get it right.”