With slim majorities in Congress and an ally in the White House, the Democrats who drafted the Environmental Justice for All Act, a comprehensive piece of federal legislation that aims to address environmental disparities in vulnerable communities across the country, are “exceedingly optimistic” that their groundbreaking bill will become law. On Thursday, they officially reintroduced the bill on Capitol Hill.

“With new leadership in Congress and the White House, we’re in a window of opportunity to save lives and establish environmental justice that the country can’t afford to miss,” said Representative Raúl Grijalva of Arizona in a statement on Thursday. “Today is the first step in pushing this bill and the principles behind it as far as they can go in our federal government.”

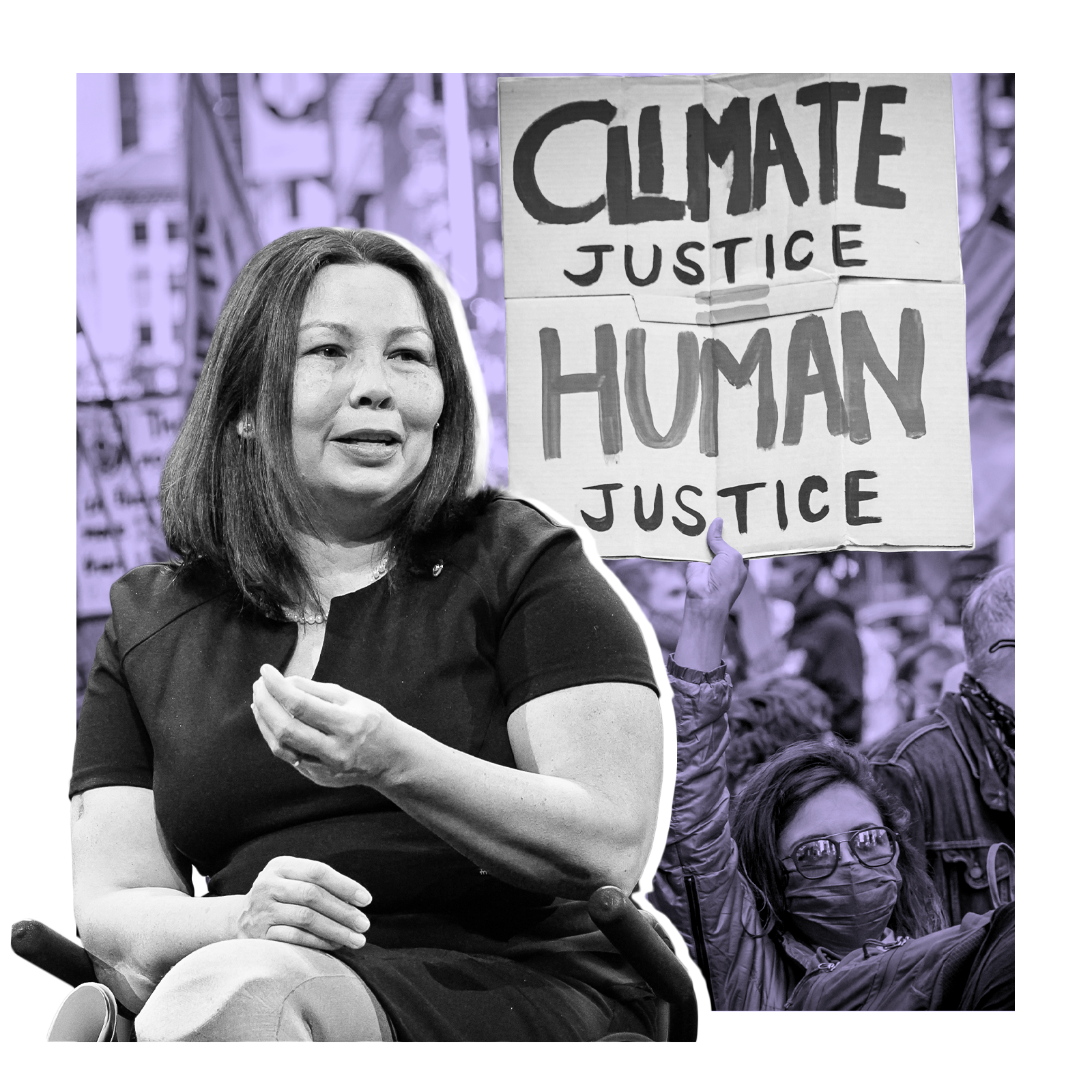

Grijalva, who is chair of the House Natural Resources Committee, reintroduced the bill into the House of Representatives with Representative A. Donald McEachin of Virginia, who co-authored the bill. Meanwhile, Senator Tammy Duckworth of Illinois, who is co-chair and co-founder of the Senate’s first environmental justice caucus, followed suit in the legislature’s upper chamber. She is picking up where Vice President Kamala Harris left off when she first introduced a companion environmental justice bill into the Senate last summer. McEachin told Grist that he has high hopes the bills will pass in both the House and the Senate.

“Will compromise be involved? Certainly. But prayerfully, the bedrock principles of the bill will survive and go to the president’s desk, and be signed, and start the process of helping these communities who for so long have been disenfranchised, and for so long been the subject of environmental injustice,” said McEachin.

Duckworth, a lead cosponsor of the original Senate bill with New Jersey Democrat Cory Booker, told Grist that she’s proud to introduce legislation that addresses public health inequities that have long existed in communities disproportionately burdened by environmental pollutants — disparities that have become undeniable during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We’ve always known that there was not health equity in this country with access to health care, but we didn’t see how bad it was until we started seeing the death rates among Black and brown communities from COVID-19,” said Duckworth, who is also chair of the Senate Environment and Public Works Subcommittee on Fisheries, Water and Wildlife, which has jurisdiction over the Safe Drinking Water Act and the Clean Water Act.

The Environmental Justice for All Act has been in the making for more than two years and is part of the lawmakers’ larger effort to elevate environmental justice in federal policy. The bill acknowledges how factors such as segregation and racist zoning practices have rendered communities of color more vulnerable to the effects of pollution and climate change, in addition to leaving them with limited resources to address ongoing environmental health disparities. The bill aims to directly engage communities like these in government decision-making processes, such as federal permitting for infrastructure projects subject to the National Environmental Policy Act, the creation of climate resiliency plans, and the transition to clean energy.

The bill’s sponsors continued to do virtual outreach throughout the pandemic to engage communities suffering under the dual effects of COVID-19 and long-standing exposure to environmental toxins and pollution. In addition to hosting virtual community roundtable discussions throughout the past year, the lawmakers have also been pressing President Joe Biden to aggressively wield executive action to promote environmental justice.

Last month, McEachin and Duckworth penned a letter to the new president urging him to prioritize eight issues, including mandatory pollution reduction, as well as financial relief and investment in low-income areas, communities of color, and Indigenous communities. They recommended that the president create a climate justice resiliency fund at the Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA, to help disadvantaged communities respond to climate change-related effects and transition to clean energy economies.

Duckworth said that the Biden administration has been receptive to her entreaties to engage on these issues, and that she’s been in conversation with new EPA Administrator Michael Regan. The immensity of the environmental threats faced by disadvantaged communities requires that all levels of the federal government do their part to address the problem, she added.

“I wanted to make sure that we come to an agreement — that’s why I sent the letter that I did — that we agree on the fundamental precept that every American has the right to breathe safe air, drink clean water, and live on uncontaminated land regardless of their zip code, how wealthy they are, the color of their skin,” said Duckworth.

Many of the issues that the bill’s sponsors pressed Biden to prioritize are also incorporated into the Environmental Justice for All Act. For example, the law would codify and make enforceable a long-standing executive order on environmental justice that then-President Bill Clinton signed in 1994. The order requires federal agencies to develop plans to remedy environmental injustice, but advocates say that agencies have not followed through.

The Act also seeks to empower private citizens and organizations to seek legal remedies when a federal program, policy, or practice has discriminatory effects; provide $75 million annually for research and program development grants to reduce health disparities and improve public health in disadvantaged communities; levy new fees on oil, gas, and coal companies to create a Federal Energy Transition Economic Development Assistance Fund, which would support workers and communities transitioning away from greenhouse gas-dependent jobs; and require federal agencies to consider health effects that might accumulate over time when making permitting decisions under the federal Clean Air and Clean Water Acts.

For McEachin, all of this is designed to promote a rapid-response, whole-of-government approach for federal agencies moving forward with plans to address the climate crisis — and to recognize that different communities have different needs.

“These communities, while they may all be EJ [environmental justice] communities, they all oftentimes have different needs — they face different challenges,” said McEachin. “So it’s important that we empower them to be able to help themselves and make sure that the federal government is in a place, agency by agency, to help them as well.”

Executive orders issued by Biden may be able to more immediately address some of the issues tackled by the bill, according to McEachin. For example, the National Environmental Policy Act, the landmark 1970 environmental law requiring federal agencies to assess the environmental effects of proposed actions such as federal infrastructure projects, was weakened by the Trump administration last year but could be strengthened again by Biden through executive action. But other elements of the bill, such as requiring cumulative analyses of environmental health effects, will require Congressional action.

“Congress is still going to have a very important role to play in moving the Environmental Justice For All Act forward,” said McEachin.

While the road ahead will be challenging, McEachin said that he and Grijalva are both excited to be working with Duckworth, who plans to focus on building a broad coalition behind the bill in the Senate. His hope is that his Republican colleagues will be part of this effort, despite the partisan polarization that has taken hold in Congress in recent decades.

“Fortunately we have the ability to move these bills without their help,” said McEachin, “but for the sake of the union it would be better if they came along — and if we can find some common ground.”