This story is part of the Grist series Parched, an in-depth look at how climate change-fueled drought is reshaping communities, economies, and ecosystems.

For the first time, the United States government will approach water scarcity as a national security issue, Vice President Kamala Harris said this week.

The policy shift is part of the newly announced White House Action Plan on Global Water Security, which aims to “elevate water security” as an international priority. The strategy calls on the U.S. to take steps to decrease instability caused by dwindling global water supplies, an issue made more severe by climate change.

“This action plan will help our country prevent conflict and advance cooperation among nations, increase equity and economic growth, and make our world more inclusive and resilient,” Harris said in a speech on Wednesday. “Water scarcity is a global problem, and it must be met with a global solution.”

Water security is defined by the United Nations as the ability to access adequate amounts of “acceptable quality water” to sustain human health, livelihoods, and socioeconomic development, while also preventing water pollution and water-related disasters, as well as preserving ecosystems. By 2030, almost half the global population will experience “severe water stress” due to climate change and population growth, the new White House action plan points out, with communities lacking access to safe drinking water and sanitation as well as water for agriculture and energy.

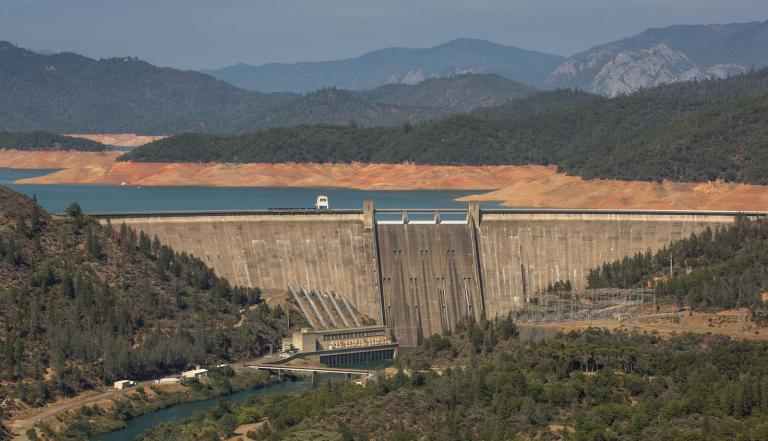

The plan acknowledges that the U.S. faces a host of water crises within its own borders, from the dangers posed by lead pipes and other forms of aging water infrastructure to the decades-long megadrought in the West that’s stressing agricultural areas, urban centers, and tribal nations alike. Under the bipartisan infrastructure law passed last fall, the government will fund $63 billion in investments to address domestic issues like lead contamination, increase drinking water access, and boost drought resilience in the years ahead.

But the new national security strategy builds on previous warnings that global water insecurity can affect the U.S., too. Last October, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence released a report outlining the effects of climate change on national security, warning that with rising temperatures, “there is a growing risk of conflict over water and migration” that could end up “creating additional demands on U.S. diplomatic, economic, humanitarian, and military resources.”

Though the action plan announced by Harris did not include dollar amounts, it instructed U.S. agencies to assist communities with financing projects to provide water and sanitation infrastructure. It expressed support for technological solutions like desalination, a controversial process that involves removing the salt from seawater and requires large amounts of energy, though it emphasized that doing so should not rely on fossil fuels. At the same time, it also said the U.S. would help countries conserve and better manage their water by sharing data and technological expertise, allowing communities to more accurately prepare for shifting water availability due to climate change.

Although the link between water and conflict isn’t always direct, a wide body of research backs up the idea that water scarcity helps drive conflict or makes it more likely to happen in regions that are already struggling with other problems. Lack of access to water makes it more difficult for communities to produce food and promote economic growth, which can lead to mass protests as well as migration that puts pressure on neighboring countries. (Though not mentioned in the action plan, a hallmark of Harris’ vice presidency has been urging migrants from Central America, many of whom have faced increasing climate impacts in their home countries, to not migrate to the U.S.).

And although “water wars” haven’t broken out on the scale that some leaders predicted, disputes over limited water resources can still provoke armed conflict. Research from the Pacific Institute, a U.S.-based nonprofit that studies issues related to water access and resilience, shows that over the last decade, water has become a more common “trigger” for conflict than a weapon or casualty of war.

These pressures have already driven conflicts in the Sahel region of Africa, where a growing population and declining water resources exacerbated by climate change have led to tensions between farmers and pastoralists, causing an estimated 15,000 deaths since 2010. In 2021, protests erupted in Iran over water shortages, leading to a government crackdown.

The new White House plan was applauded by nonprofit organizations like the World Wildlife Fund, which emphasized the need to create “resilient” water systems that can withstand shocks like climate change. Others pointed out the role that the U.S. must play in addressing climate change as one of the world’s biggest sources of greenhouse gases, the root cause of climate-driven drought.

“Freshwater ecosystems harbor a wealth of critical resources for humanity, including drinking water, food, and means for economic growth,” Sarah Davidson, the fund’s director of freshwater policy, said in a statement. “We welcome the Administration’s plan to elevate water security and resilience, and support immediate steps to integrate freshwater health into sound infrastructure, energy, development, and climate-smart investments at home and abroad.”