No matter where you live, extreme weather can hit your area, causing damage to homes, power outages, and dangerous or deadly conditions. If you’re on the coast, it may be a hurricane; in the Midwest or South, a tornado; in the West, wildfires; and as we’ve seen in recent years, anywhere can experience heat waves or flash flooding.

Living through a disaster and its aftermath can be both traumatic and chaotic, from the immediate losses of life and belongings to conflicting information around where to access aid. The weeks and months after may be even more difficult, as the attention on your community is gone but civic services and events have stalled or changed drastically.

Grist compiled this resource guide to help you stay prepared and informed. It looks at everything from how to find the most accurate forecasts to signing up for emergency alerts to the roles that different agencies play in disaster aid.

Where to find the facts on disasters

These days, many people find out about disasters in their area via social media. But it’s important to make sure the information you’re receiving is accurate. Here’s where to find the facts on extreme weather and the most reliable places to check for emergency alerts and updates.

Your local emergency manager: Your city or county will have an emergency management department, which is part of the local government. In larger cities, it’s often a separate agency; in smaller communities, fire chiefs or sheriff’s offices may manage emergency response and alerts. Emergency managers are responsible for communicating with the public about disasters, managing rescue and response efforts, and coordinating between different agencies. They usually have an SMS-based emergency alert system, so sign up for those via your local website (Note: Some cities have multiple languages available, but most emergency alerts are only in English.) Many emergency management agencies are active on Facebook, so check there for updates as well.

Local news: The local television news and social media accounts from verified news sources will have live updates during and after a storm. Follow your local newspaper and television station on Facebook or other social media, or check their websites regularly.

Weather stations and apps: The Weather Channel, Apple Weather, and Google will have information on major storms, but that may not be the case for smaller-scale weather events, and you shouldn’t rely on these apps to tell you if you need to evacuate or move to higher ground.

National Weather Service: This agency, also known as NWS, is part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and offers information and updates on everything from wildfires to hurricanes to air quality. You can enter your zip code on weather.gov and customize your homepage. The NWS also has regional and local branches where you can sign up for SMS alerts. If you’re in a rural area or somewhere that isn’t highlighted on its maps, keep an eye out for local alerts and evacuation orders, as NWS may not have as much information ahead of time.

How to pack an emergency kit

As you prepare for a storm, it’s important to have an emergency kit ready in case you lose power or need to leave your home. Review this checklist from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, or FEMA, for what to pack so you can stay safe, hydrated, and healthy.

These can often be expensive to create, so contact your local disaster aid organizations, houses of worship, or charities to see if there are free or affordable kits available. Try to gather as much as you can ahead of time in case shelves are empty when a storm is on the way.

Some of the most important things to have:

- Water (one gallon per person per day for several days)

- Food (at least a several-day supply of non-perishable food) and a can opener

- Medicines and documentation of your medical needs

- Identification and proof of residency documents (see a more detailed list below)

- Battery-powered or hand crank radio, batteries, flashlight

- First aid kit

- Masks, hand sanitizer, and trash bags

- Wrench or pliers

- Cell phone with chargers and a backup battery

- Diapers, wipes, and food or formula for babies and children

- Food and medicines for any household pets

Don’t forget: Documents

One of the most important things to have in your emergency kit is documents you may need to prove your residence, demonstrate extent of damage, and vote. FEMA often requires you to provide these documents in order to receive financial assistance after a disaster.

- Government issued ID, such as a drivers’ license for for each member of your household

- Proof of citizenship or legal residency for each member of your household (passport, green card, etc.)

- Social Security card for each member of your household

- Documentation of your medical needs, such as medications or special equipment including oxygen tanks, wheelchairs, etc.

- Health insurance card

- Car title and registration documents

- Pre-disaster photos of the inside and outside of your house and belongings

- Copy of your homeowners’ or renters’ insurance policy

- For homeowners: copies of your deed, mortgage information, and flood insurance policy, if applicable

- For renters: a copy of your lease

- Financial documents such as a checkbook or voided check

You can find more details about why you may need these documents here.

Yuki Iwamura/AFP via Getty Images

Disaster aid 101

It can be hard to know who to lean on or trust when it comes to natural disasters. Where do official evacuation orders come from, for example, or who do you call if you need to be rescued? And where can you get money to help pay for emergency housing or to rebuild your home or community. Here’s a breakdown of the government officials and agencies in charge of delivering aid before, during, and after a disaster:

Emergency management agencies: Almost all cities and counties have local emergency management departments, which are part of the local government. Sometimes they’re agencies all their own, but in smaller communities, fire chiefs or sheriff’s offices may manage emergency response and alerts. These departments are the first line of defense during a weather disaster. They’re responsible for communicating with the public about incoming disasters, managing rescue and response efforts during an extreme weather event, and coordinating between different agencies. Many emergency management agencies, however, have a small staff and are under-resourced.

Much of the work that emergency managers do happens before a disaster: They develop response plans that lay out evacuation routes and communication procedures, and they also delegate responsibility to different government agencies like the police, fire, and public health departments. Most counties and cities publish these plans online.

In most cases, they are the most trustworthy resource in the days just before and just after a hurricane or other big weather event. They’ll send out alerts and warnings, coordinate evacuation efforts, and direct survivors and victims to resources and shelter.

You can find your state emergency management agency here. There isn’t a comprehensive list by county or city, but if you search your location online you’ll likely find a website, a page on the county or city website, or a Facebook page that posts updates.

Law enforcement: County sheriffs and city police departments are often the largest and best-staffed agencies in a given community, so they play a key role during disasters. Sheriff’s departments often enforce mandatory evacuation orders, going door-to-door to ensure that people vacate an area. They manage traffic flow during evacuations and help conduct search and rescue operations.

Law enforcement agencies may restrict access to disaster areas for the first few days after a flood or fire. In most states, city and county governments also have the power to issue curfew orders, and law enforcement officers can enforce these curfews with fines or even arrests. In some rural counties, the sheriff’s department may serve as the emergency management department.

Governor: State governors control several key aspects of disaster response. They have the power to declare a state of emergency, which allows them to deploy rescue and repair workers, distribute financial assistance to local governments, and activate the state National Guard. The governor has a key role in the immediate response to a disaster, but a smaller role in distributing aid and assistance to individual disaster victims.

In almost all U.S. states, and all hurricane-prone states along the Gulf of Mexico, the governor also has the power to announce mandatory evacuation orders. The penalty for not following these orders differs, but is most often a cash fine. (Though states seldom enforce these penalties.) The state government also decides whether to implement other transportation procedures such as contraflow, where officials reverse traffic flow on one side of a highway to allow larger amounts of people to evacuate.

HUD: The Department of Housing and Urban Development, or HUD, also spends billions of dollars to help communities recover after disasters, building new housing and public buildings such as schools — but this money takes much longer to arrive. Unlike FEMA, HUD must wait for Congress to approve its post-disaster work, and then it must dole out grants to states for specific projects. In some cases, such as the aftermaths of Hurricane Laura in Louisiana or Hurricane Florence in North Carolina, it took years for projects to get off the ground. States and local governments, not individual people, apply for money from HUD, but the agency can direct you to FEMA or housing counselors.

FEMA

The Federal Emergency Management Agency, or FEMA, is the federal government’s main disaster response agency. It provides assistance to states and local governments during large events like hurricanes, wildfires, and floods. FEMA is part of the Department of Homeland Security.

FEMA is almost never the first resource on the ground after a disaster strikes. In order for the agency to send resources to a disaster area, the state’s governor must first request a disaster declaration from the president, and the president must approve it. For large disasters such as Category 4 or 5 hurricanes, this typically happens fast. For smaller disasters, like severe rain or flooding events, it can take weeks or even months for the president to grant a declaration and activate the agency. FEMA has historically not responded to heat waves.

FEMA is broken into regional offices and offers specific contacts and information for each of those, as well as for tribal nations. You can find your FEMA region here.

FEMA has two primary roles after a federally declared disaster:

Contributing to community rebuilding costs: The agency helps states and local governments pay for the cost of removing debris and rebuilding public infrastructure. During only the most extreme events, the agency also deploys its own teams of firefighters and rescue workers to help locate missing people, clear roadways, and restore public services. For the most part, states and local law enforcement conduct on-the-ground recovery work. (Read more about FEMA’s responsibilities and programs here.)

Individual financial assistance: FEMA gives out financial assistance to individual people who have lost their homes and belongings. This assistance can take several forms. FEMA gives out pre-loaded debit cards to help people buy food and fuel in the first days after a disaster, and may also provide cash payments for home repairs that your insurance doesn’t cover. The agency also provides up to 18 months of housing assistance for people who lose their homes in a disaster, and sometimes houses disaster survivors in its own manufactured housing units or “FEMA trailers.” FEMA also sometimes covers funeral and grieving expenses as well as medical and dental treatment.

In the aftermath of a disaster, FEMA offers survivors:

- A one-time payment of $750 for emergency needs

- Temporary housing assistance equivalent to 14 nights’ stay in a hotel in your area

- Up to 18 months of rental assistance

- Payments for lost property that isn’t covered by your homeowner’s insurance

- And other forms of assistance, depending on your needs and losses

If you are a U.S. citizen or meet certain qualifications as a non-citizen and live in a federal disaster declaration area, you are eligible for financial assistance. Regardless of citizenship or immigration status, if you are affected by a disaster you may be eligible for crisis counseling, disaster legal services, disaster case management, medical care, shelter, food, and water.

FEMA also runs the National Flood Insurance Program, which provides insurance coverage of up to $350,000 for home flood damage. The agency recommends that everyone who lives in a flood zone purchase this coverage — and most mortgage lenders require it for borrowers in flood zones — though many homes outside the zones are also vulnerable. You must begin paying for flood insurance at least 30 days before a disaster in order to be eligible for a payout. You can check if your home is in a flood zone by using this FEMA website.

How to get FEMA aid: The easiest way to apply for individual assistance from FEMA is to fill out the application form on disasterassistance.gov. This is easiest to do from a personal computer over Wi-Fi, but you can do it from a smartphone with cellular data if necessary. This website does not become active until the president issues a disaster declaration.

Some important things to know:

- FEMA will require you to create an account on the secure website Login.gov. Use this account to submit your aid application.

- You can track the status of your aid application and receive notifications if FEMA needs more documents from you.

- If FEMA denies your application for aid, you can appeal, but the process is lengthy.

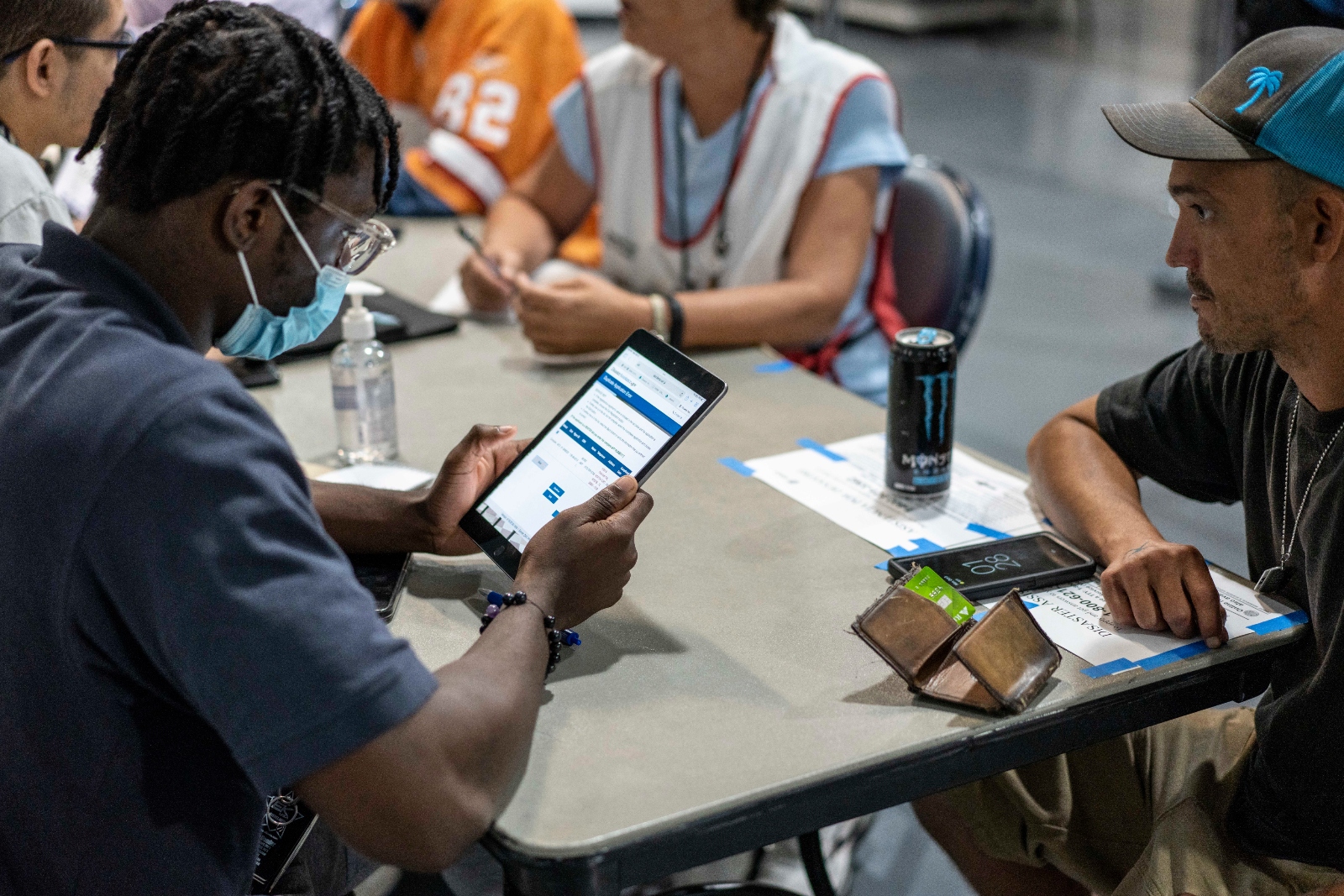

Visiting a FEMA site in your area after a disaster: FEMA disaster recovery centers are facilities and mobile units where you can find information about the agency’s programs as well as other state and local resources. FEMA representatives can help you navigate the aid application process or direct you to nonprofits, shelters, or state and local resources. Visit this website to locate a recovery center in your area or text DRC and a ZIP Code to 43362. Example: DRC 01234.

What to expect after a disaster

Disasters affect people in many different ways, and it’s normal to grieve your losses — personal, professional, community — in your own time. Here are a few resources if you need mental health support after experiencing an extreme weather event.

- The National Center for PTSD, or post-traumatic stress disorder, on what to expect after experiencing a disaster.

- The American Red Cross has disaster mental health volunteers they often dispatch to areas hit by a disaster.

- The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, or SAMHSA, has a fact sheet on managing stress after a disaster. The agency has a Disaster Distress Helpline that provides 24/7 crisis counseling and support. Call or text: 1-800-985-5990

After a disaster is an especially vulnerable time. Beware of scams and make sure to know your rights.

- Be wary of solicitors who arrive at your home after a disaster claiming to represent FEMA or another agency. FEMA will never ask you for money. The safest way to apply for aid is through FEMA’s official website: disasterassistance.gov.

- Be cautious about hiring contractors or construction workers in the days after a disaster. Many cities require permits for rebuilding work, and it’s common for scammers to pose as contractors after a disaster.

- Renters can often face evictions after a disaster, so familiarize yourself with tenant rights in your state.

What to keep in mind before, during, and after a disaster

The most important thing to consider during a disaster is your own, your family’s, and your community’s safety. The National Weather Service has a guide for hurricanes and floods; FEMA has a guide for wildfires; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has a guide for extreme heat safety.

A few potentially life-saving things to remember:

- Never wade in floodwaters. They often contain harmful runoff from sewer systems and can cause serious illness and health issues.

- If it’s safe to do so, turn off electricity at the main breaker or fuse box in your home or business before a hurricane to prevent electric shock.

- If you lose power, never operate a generator inside your home. Generators emit carbon monoxide, a colorless and odorless gas that can be fatal if inhaled.

Did we miss something? Please let us know by emailing community@grist.org.