As our climate changes, so will our diets. Fix is exploring that reality through the lens of foods that show what sustainable, equitable, and resilient eating could look like. Try them yourself with the recipes in our Climate Future Cookbook.

Al Massa grew up in an Italian family, learning the art of cooking while helping his mother trim tenderloins and prepare mounds of pasta on Sundays. She instilled in him an abiding love of gourmet food, one that was nurtured in Europe and expanded with Creole cuisine while working for the empire of celebrity chef Emeril Lagasse in New Orleans kitchens. These days, Massa is executive chef at a popular seafood restaurant in the coastal fishing town of Destin on Florida’s Gulf Coast.

The town also is home to a far less welcome resident: The lionfish. The nonnative and voracious predator has in recent decades invaded the Sunshine State’s coastal reefs, wreaking havoc on the ecosystem.

Massa is one of those leading the charge on an increasingly popular way of dealing with the threat — one with a surprising range of environmental benefits: Serving them for dinner. “With lionfish, it’s beneficial to harvest more of them. The more we get out, the more other fish, like snapper and grouper, will survive,” says Massa. “Plus, they taste good.”

A growing number of foodies, conservationists, and government officials are encouraging people to eat the nonnative animals. The way they see it, serving the mild, flaky fish — say, with forbidden rice or in a mango-accented ceviche — is an excellent way to combat its proliferation and mitigate the damage it is doing in the Caribbean and along the Gulf and Atlantic coasts. The animals pose so dire a threat that Florida has placed a bounty on their tails and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration argues, “If you can’t beat them, eat them!”

It’s perhaps a surprising position for an organization that typically promotes sustainable fishing. “We want to fish them unsustainably, in a way, for conservation purposes,” says Steve Gittings, the science coordinator for that agency’s National Marine Sanctuaries program. “The whole point of getting rid of them is to get rid of them.”

The merciless campaign is a prime example of a rising effort to make nonnative species like wild pigs and garden snails a viable alternative to more popular, and carbon-intensive, proteins — particularly as climate change drives invasives into new regions. Lionfish are an attractive substitute for overfished species like halibut and snapper because they are relatively abundant; making them a common dinnertime choice would ease pressure on the Atlantic’s strained fisheries.

Lionfish tastes a bit like halibut or snapper (and can replace them in most dishes) and is winning fans at those restaurants serving it. For now, though, lionfish remains hard to find in the U.S. beyond Florida, and even there it is a pricey delicacy. The tenacious survivors are labor-intensive to catch. Realizing the conservation and sustainability benefits of lionfish hinges on ongoing efforts to develop effective methods of hunting them.

“There is a demand,” says Gittings. “People would like lionfish. It’s just hard to get them.”

* * *

Lionfish are easily identified by their maroon and cream-colored stripes and venomous, spiky fins that resemble a clown’s version of a lion’s mane. Native to the Indo-Pacific region, the marine marauders are suspected to have been introduced to Florida coasts in the 1980s by home aquarists dumping unwanted pets. In the decades since, the fish found new homes in the Atlantic from Brazil to North Carolina and portions of the Caribbean and Gulf Coast, according to Gittings, NOAA, and ongoing scientific studies.

Although researchers believe their numbers appear to have peaked in 2018, warming seas allow lionfish to migrate as far north as Rhode Island in summertime. They thrive in waters warmer than 60 degrees F, and marine biologists worry that climate change will allow the animals to settle in more regions. That is especially concerning because a single female can release as many as 2 million eggs each year.

All of this poses a grave threat to native species because the ravenous lionfish has no known predators in the Atlantic region. They eat a wide variety of crustaceans and small fish, particularly the young, called fry, of larger species, and by some accounts can reduce the native fish population of a reef by about 80 percent. That imperils recreationally and commercially important species such as snapper and grouper, as well as environmentally important species like the parrotfish, which cleans algae from corals.

Massa remembers the first time he saw the flamboyant fish in a seafood case at Whole Foods: Seeing the array of spikey fins and colorful stripes, Massa knew he had to try it, spines and all. Although removing the venomous fins requires care, the lionfish is, like rattlesnake, safe to eat.

In the two years since, Massa has developed a handful of dishes, from sashimi to ceviche (which is more of a “crudo,” he says) and even fried whole with rice flour. His most dramatic technique, pan-searing a filet and serving it with forbidden rice and a vegetable confit, is popular with diners at Brotula’s Seafood House and Steamer, where he is executive chef. It has impressed his peers as well — the recipe took second place at the Great American Seafood Cook-off in August, something Massa believes could help convince people just how delicious this “trash” species can be.

“You can take a bite and take a smile because you’re doing something good for the ecosystem,” he says. “You also can smile because it tastes so good.”

As someone who likes to fish, Massa has seen the harm overfishing is causing to Florida’s coastal waters. Many popular varieties are harder to catch, and those being reeled in are smaller than they’ve been in the past. In his opinion, Chilean sea bass is delicious, but including it on his menu simply isn’t worth the environmental price. Better to serve lionfish.

Given the reaction he’s seen to his lionfish dishes, the challenge isn’t getting people to eat lionfish. It’s catching enough of them to make a difference.

* * *

The lazy lionfish prefer to lounge around reefs, which makes them difficult to capture with nets that can snag on the delicate ecosystems. The fish also rarely eat anything that doesn’t swim within easy reach, so they don’t tend to bite baited hooks. That leaves spearfishing, an adventurous but time-consuming endeavor, as the only means of catching them.

Rachel Bowman finds that depths of about 100 feet along the Florida Keys are a sweet spot for spearing the swimmers, which can be found at depths as great as 1,000 feet but thrive at 100 to 300 feet. She’s been hunting lionfish since 2012, when she first plunged backward off a boat to stalk the artificial reef created by sinking the cargo ship Adolphus Busch Sr. Once she understood the damage lionfish were doing to Florida’s coastal ecosystems, she was hooked on catching as many as possible.

She prefers to dive at dawn or dusk, when lionfish are most active, on her days off from bartending and managing a local seafood restaurant. After sinking to the bottom, heavy with scuba gear, she’ll ride the gentle current scanning the reef for her prey and checking nooks and crannies for the small fish and fry they like to eat, which resemble glitter thrown into the sea.

“Lionfish will just sit there and eat fry all day long, just like you’ll sit in your car and eat French fries all day long,” Bowman says. Some dives she might spear no more than five fish. Others, she’ll collect as many as 80. It all depends on the conditions and her luck.

Solitary divers spearing lionfish one by one is not a terribly efficient way of catching them, which explains the growing popularity — among fishing enthusiasts and restaurateurs alike — of hunting tournaments. They started around 20 years ago in the Bahamas and the Florida Keys. They reached the panhandle by 2014, and this year’s Emerald Coast Open in Destin drew 145 divers who brought in 13,835 lionfish. Definitely a lot of fish, but not nearly enough to bump snapper off the menu.

“A ton of fish to us as divers is a drop in the bucket” compared to industrial fishing methods like trawling, says Alex Fogg, coastal resource manager in Destin-Fort Walton Beach and an avid diver and fisher who hosts the Emerald Coast Open.

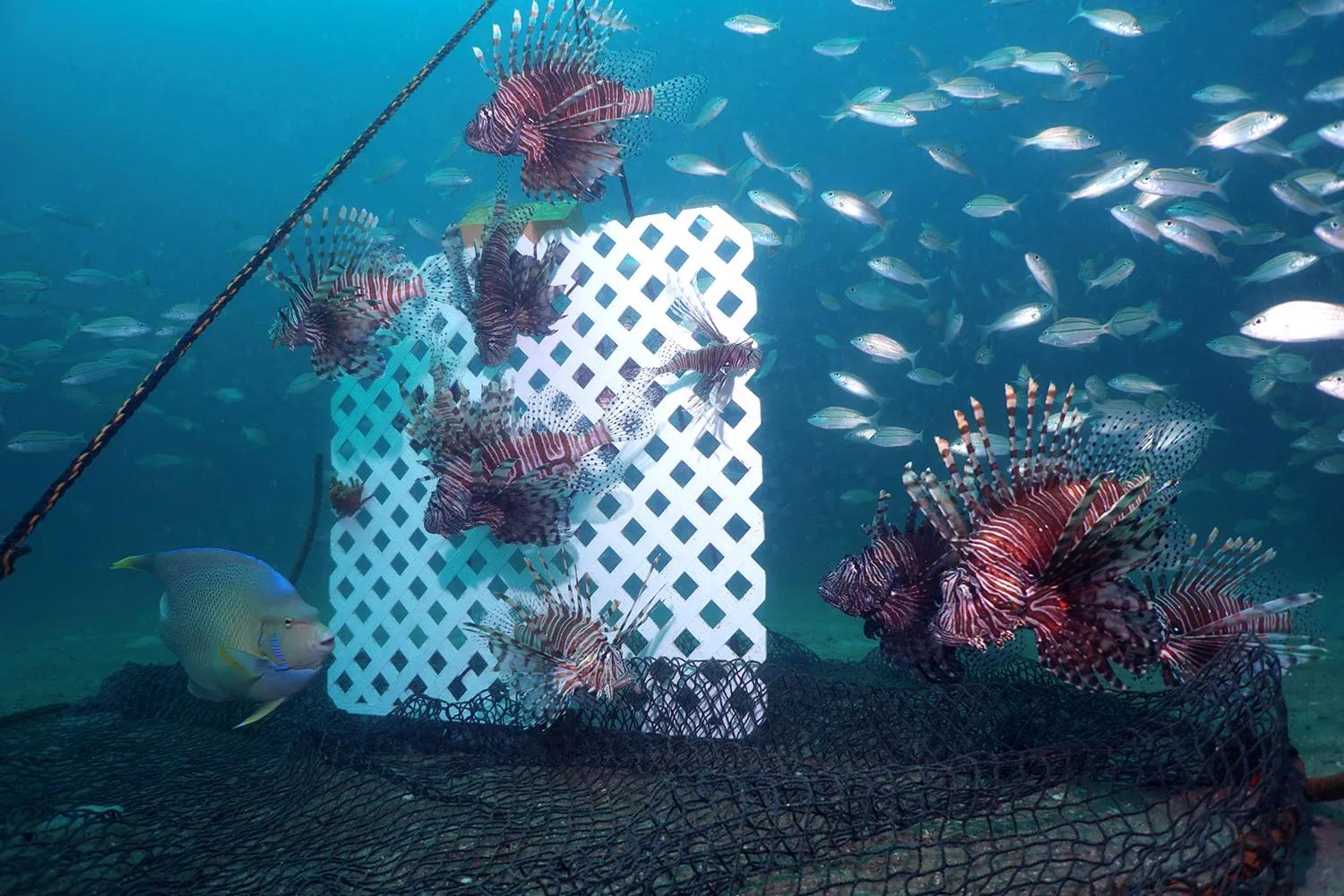

That’s why he and others hope a new kind of lionfish trap catches on. NOAA’s Gittings is among those developing viable methods that could make catching the sluggish swimmers much easier.

The animals favor natural coral reefs and structures like sunken boats, so the design capitalizes on that behavior. Gittings designed a 6-foot circular net attached to a steel frame that lays flat on the seafloor. A lure that resembles patio fencing at the center attracts its prey. When it’s time to retrieve the bounty, a sharp tug on the cable snaps the device shut like a Venus flytrap, catching the slow-moving fish while any quicker species in the vicinity get away. The design eliminates the risk of “ghost fishing” should the equipment be lost. If all goes well during commercial testing, the traps could allow fishers to work in waters too deep for spearfishing and bring the beasts ashore in greater numbers.

“By the end of this year, we’ll have an inkling what they’re thinking,” Gittings says of the pros now working with the contraptions. He’s optimistic that all will go according to plan and the traps could make lionfish more common in markets and restaurants. “That could take some pressure off other species,” he says.

Since each lionfish yields a relatively small amount of meat — about 25 percent of their total body weight, which averages between 1 and 2 pounds — finding uses for the rest of it would help offset the cost of harvesting them. A cottage industry of artists makes jewelry with the animal’s bones and spikey bits, and Florida startup Inversa Leathers uses the scaly skin to craft sustainable leather. Italian sneaker maker P448 used the material to make a pair of high-end kicks that it unveiled in Paris this summer.

But until there are more efficient ways of getting lionfish out of the water and into boutiques and bistros beyond the Gulf Coast, their limited availability remains the biggest challenge to creating a supply chain that could help mitigate their impact on reef ecosystems and minimize the possibility that climate change will drive the fish ever northward. Gittings’s traps may be the best chance of realizing those goals.

“I took them as far as I could with [my] experiments,” he says. “Now it’s time for the fishermen.”

Read more from the Climate Future Cookbook:

- How perennial wheat could reverse the damage of industrial agriculture

- Precision fermentation may be the secret to better vegan cheese

- At an urban farm, a community connects to their food and to each other