Chicken houses along the Pocomoke River, which empties into the Chesapeake Bay. (Photo by IAN.)

According to Meatingplace.com (subscription required), Tyson and Perdue both want to build “hundreds” of chicken houses near their vast slaughter facilities in Accomack County, Va.

“Perdue’s plant there processes more than 82 million birds a year,” Meatingplace reports. The plant draws in birds from as “far away as Suffolk, Del., and North Carolina.” And to “reduce the turnaround time between farm and processing plant,” Perdue wants lots more poultry production in or near Accomack County.

How many more chicken houses would satisfy its appetite? Meatingplace quotes a Perdue functionary: “We could do 300 more houses right now.”

As for Tyson, it “needs 125 additional houses nearby to adequately supply the [Accomack County] plant but is restricted by Maryland land-use regulations.”

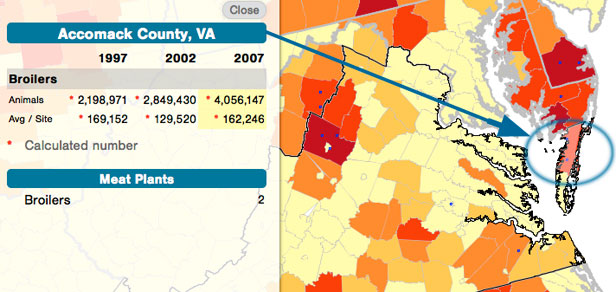

What does all of this mean? Let’s turn to Food & Water Watch’s shiny new Factory Farm Map tool, which I enthused about yesterday here.

The FWW tool breaks down Accomack County’s existing factory animal population thusly.

Screenshot: Food & Water Watch

Screenshot: Food & Water Watch

Accomack County lies on what’s known as the Delmarva Peninsula. On the above map, Delmarva is the chunk of land at the right jutting down into the Chesapeake Bay. Once a dramatically productive ecosystem and one of the jewels of U.S. food production, the Chesapeake is now a virtual wasteland, ground down by decades of pollution, mainly from agriculture. An invaluable wild source of sustainable food has been sacrificed at the alter of cheap meat.

Delmarva is so named because it is the combined territory of Delaware (northeast corner), Maryland (northwest), and Virginia (southern tip). The Chesapeake is already under severe pressure from manure runoff from Delmarva’s voluminous poultry houses: algae-friendly nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorous, as well as antibiotics, antibiotic-resistant bacteria, and even arsenic.

As Waterkeepers puts it, “Billions of pounds of chicken litter have flowed into the bay in the decades since international poultry conglomerates such as Perdue and Tyson targeted the Delmarva Peninsula for their multi-million-dollar operations.” The industry has been “treating the Chesapeake Bay like an open toilet,” the group adds.

So, what the Perdue and poultry execs are pining for is an intensification of that unhappy process. The FWW tool tells us that poultry production in Accomack doubled between 1997 and 2007. The county now produces more than 4 million chickens, with each site averaging 162,000 birds. And in surrounding Delmarva counties, the situation is even more intense — the darker the red, the higher the factory-farm concentration.

Sussex County, Delaware, houses 14 million chickens (up 40 percent since 1997); Somerset County, Maryland, has seen its chicken population nearly triple to 7.2 million; and Somerset County, Maryland now raises 4.8 million hens — a sevenfold rise since 1997.

None of this is enough for Tyson and Perdue; they want more, more, more. It’s the inexorable logic of industrial agriculture: You build enormous processing facilities, such as the two in Accomack, and in order for them to be maximally profitable, you intensively concentrate production (and resulting wastes) nearby. The resulting product — in this case, low-quality chicken that’s been lashed with antibiotics and dodgy ethanol waste — gets distributed globally.

Get off your ass alert: Check out Waterkeeper’s Chesapeake Poultry Initiative, which has an action to pressure the EPA to revoke the Bush Administration’s rule allowing factory farms to hide information about toxic pollutants.