The first thing Andy Barrientes noticed when he showed up for his shift at RMS Foods on Valentine’s Day, 2005, was the cloud of black smoke emanating from the building.

A fire had started in the factory around 4:20 p.m., not long before Barrientes was scheduled to clock in as maintenance manager at the food manufacturing plant in southeastern New Mexico. The blaze had caught his coworkers coming off the day shift by surprise; they reported smelling the smoke before seeing the flames. When Barrientes arrived, he saw the staff huddled together at the park across the street. “Everyone was holding hands,” he said. “And we were just … the fire was so big.”

Barrientes had only been working at the factory for a few years. The job was something of an odd one: RMS Foods had once been a prominent meat processor in Hobbs, New Mexico, supplying local hotels and restaurants with cuts of beef and pork. But the company had recently started producing soy-based veggie burgers under the Boca Burger brand — an unlikely pivot for a part of the country better known for its cattle ranches, steakhouses, and dairy farms. Barrientes was hired around the same time as this change, and in the years since, veggie burger production had taken off.

On the day of the fire, the entire staff evacuated without injuries, allowing the fire department — which arrived within four minutes of receiving the call — to immediately set to work containing the inferno.

By 5:30 p.m., the clouds of smoke had mostly dissipated, but the building was gone. The roof of the factory had collapsed, and all but three pieces of food-processing equipment were damaged beyond repair.

Among those standing across the street in the middle of Humble Park were Sam Cobb, president of RMS Foods, and his wife, Rhonda. Cobb’s father had founded the company 46 years prior, and the plant had been standing proudly on North Grimes Street for nearly as long. The family business all but burned to the ground in about an hour. Cobb, who had taken over after working under his father for years, promptly began thinking about how to support his employees in the face of such a loss, but he had few details for what came after that. “We’ll assess the damages and see what we can do to get back in business,” he told a local reporter for the Hobbs News-Sun.

His uncertainty didn’t last long. The following day, Cobb informed the News-Sun that he was at work on a plan to continue paying his nearly 100 employees for as long as it took to rebuild the facility — although he had yet to meet with the insurance company or inform them of such a plan.

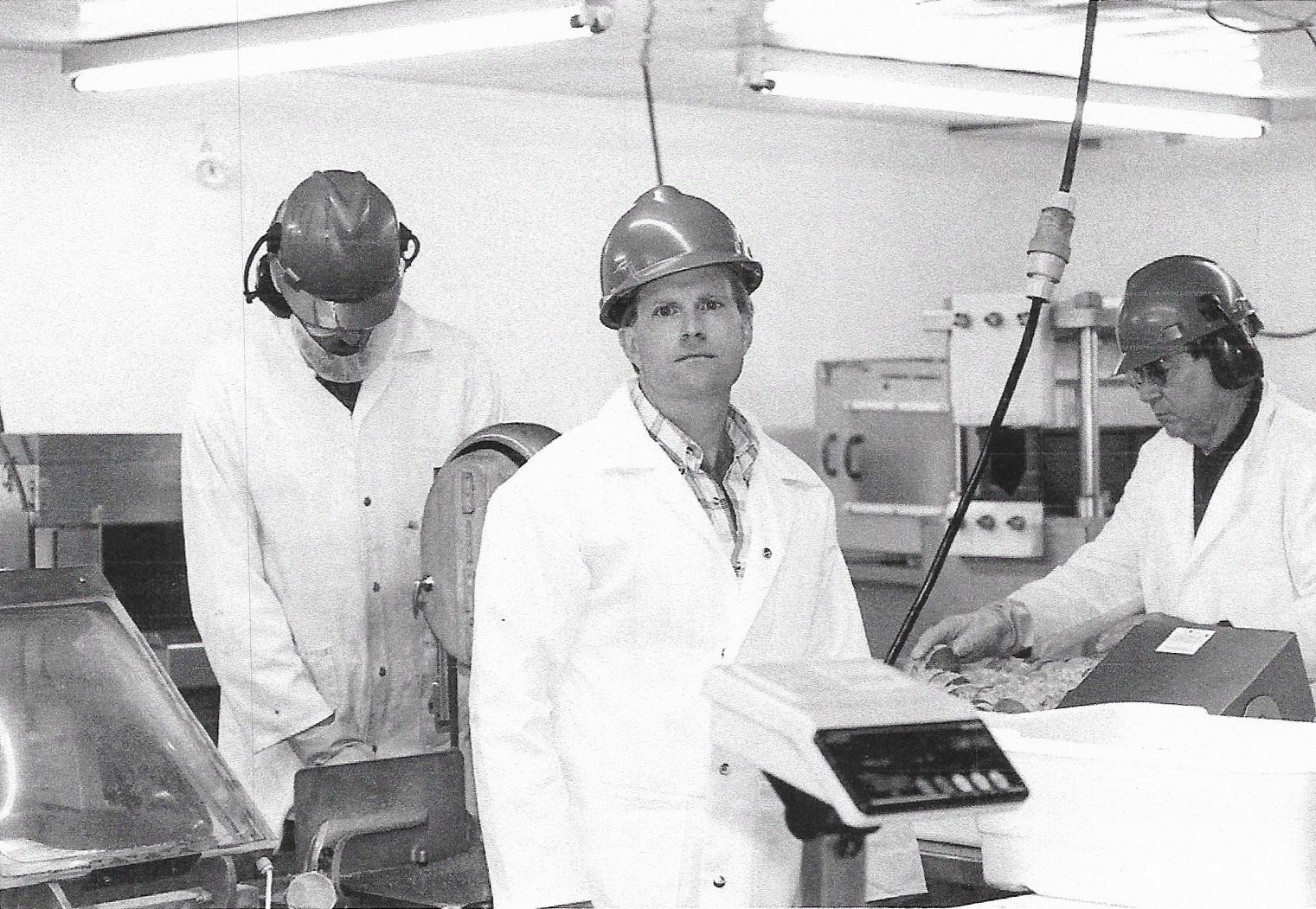

In less than a week, Cobb had negotiated a deal between the insurance company, a local construction company, and his staff. All RMS Foods employees would immediately be eligible for state unemployment benefits, and roughly a third would also be hired back to assist with the reconstruction. “From the day we started, we were actually building: running wires, putting up red iron, putting up walls, pouring concrete, doing 17 hours a day,” said Barrientes, who worked on the factory reconstruction and is still employed at RMS Foods today. “We got it done quick,” he added. The arrangement was typical of Cobb, according to Barrientes and other current employees. “He’s never said no to us. He’s always taken care of every one of his employees, and that’s why we’re all so dedicated to him,” he said, “because he’s dedicated to us.”

Just eight months later, the facility was operational again — and Boca Burgers were flying down the factory line.

Tucked away in the southeastern corner of New Mexico, just minutes from the Texas state line, Hobbs lies in the middle of the Permian Basin. Most jobs in the city of about 40,000 residents are in mining, quarrying, or oil and gas extraction, according to the local economic development council. Animal agriculture — both cattle ranching and dairy farming — also figures significantly in the region’s economy and culture.

These industries shape local attitudes toward eating; barbeque joints abound in the area and steak dinners are common. “Here in oil patch/cattle country, it is probably difficult to find people who will give any type of endorsement to any burger labeled vegetarian, or worse yet, vegan,” Robert Hamilton, a local Hobbs librarian who doesn’t eat red meat, told me.

Against a backdrop of pumpjacks and stretches of desert sky, RMS Foods is a total anomaly. “You would be surprised how many people don’t know that this is here,” said Arnold Langley, a production manager at RMS Foods who has been with the company since 2006. Langley is something of a food-manufacturing veteran — having previously worked at a french fry factory that shut down in Washington state, he was hired by RMS to help scale Boca Burger production. “I’d say I came down to Hobbs to go to work for Sam,” said Langley, “and I never looked back.”

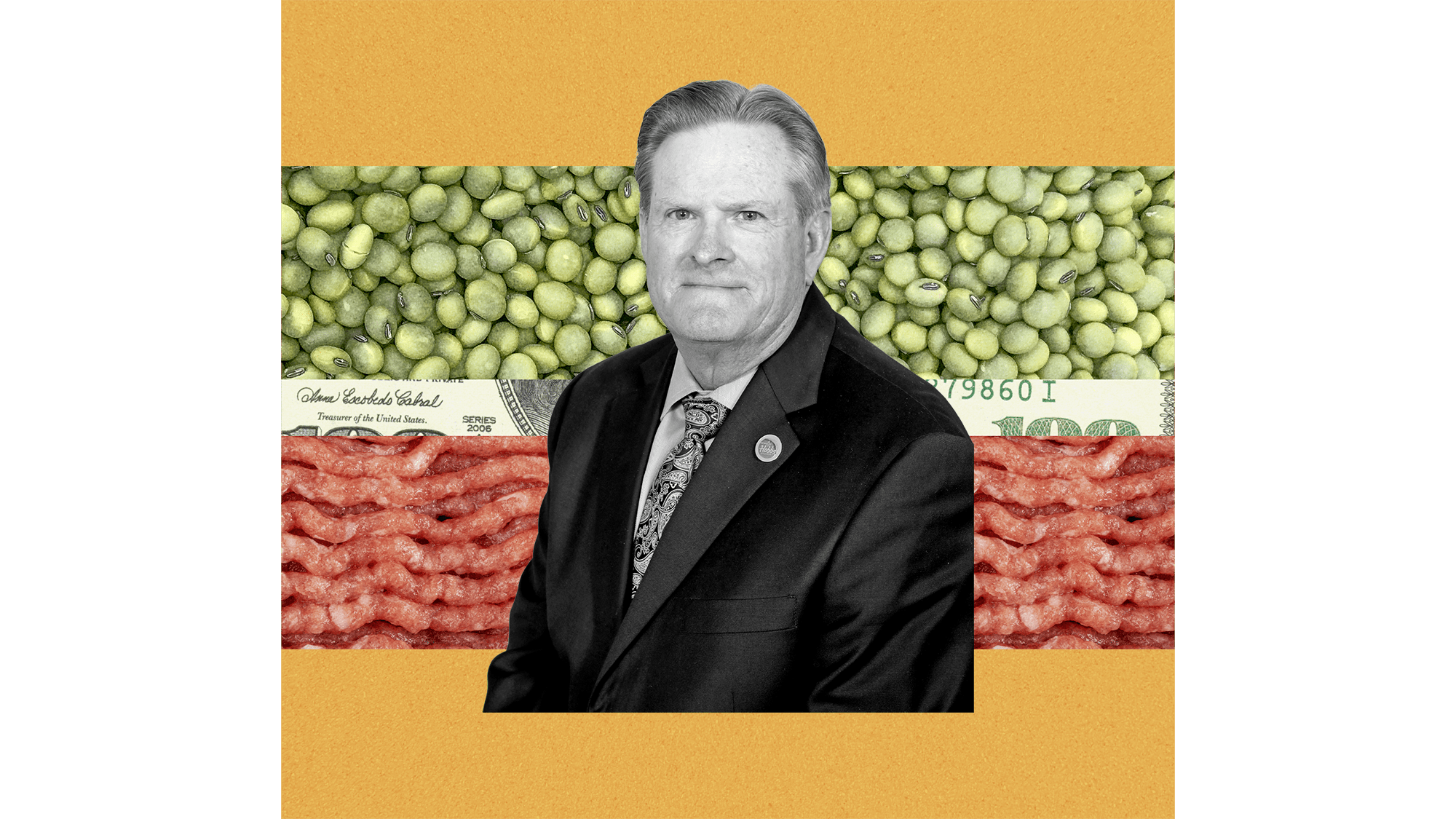

Seated in his office, in the same building his employees helped rebuild more than 20 years ago (now dedicated to Rhonda, who died in 2018), Cobb wears a crisp button-down with his salt-and-pepper hair combed back neat. On the walls are photos of friends and family, plaques for business accolades, and black-and-white shots of his days in college at Texas Tech University. An official portrait of Cobb at City Hall sits on a nearby table; Cobb served as the mayor of Hobbs from 2012 to this past January. To illustrate the evolution of RMS Foods, he pulls out various marketing materials he’s kept from over the years. There are promotional catalogs of beef and pork products, followed by cheeky magazine ads for Boca Burgers. (One reads: “The way Bob devoured his burger, you’d think no one told him it’s meatless with 70 percent less fat.”)

How Cobb reconciles his relationship to these dueling food industries is curious — his venture into the plant-based burger space only came about because of his expertise with meat processing. Cobb is aware of the paradoxes inherent to his career’s trajectory. In our first phone call, over a year ago, he conceded that non-animal sources of protein will become crucial to food security in years to come. “There’s no way that as our global population grows, everybody can have a T-bone steak every night,” he said. Additionally, greenhouse gas emissions from animal agriculture, particularly beef production, are a major contributor to climate change. Research has shown more people embracing a plant-based diet is a crucial step to reducing global emissions. But for Cobb, animal agriculture and plant-based protein have long existed alongside each other, and in his case, one supports the other. He likes to say: “I make veggie burgers for a living so I can afford to be a cowboy.”

Cobb himself is a fourth-generation rancher. In the late 1880s, his great-grandfather Gatlin Hall Cobb acquired land and started a ranch in Haskell County, Texas, which is still in the family today. Sam Cobb’s father, S.G., lived through the Great Depression and a drought in the 1950s, two events that showed him the financial precarity of raising cattle for a living. It soon became clear that the Cobb family didn’t make enough money off of the family ranch to support both generations. So S.G. left Texas and headed west to New Mexico in 1959, with the hope of one day buying his own ranch.

S.G. had a no-nonsense way about him, according to his son, and when he arrived in Hobbs, he opened a franchise of Rich Plan Corporation, a frozen-food company that sold and delivered bulk orders directly to households and even offered freezers to hold months’ worth of food. According to Cobb, when the national Rich Plan Corporation went bankrupt, S.G. maintained his relationships with livestock farmers and rebranded his company as Rich Meat Services. The company transitioned into a meat processing business, selling beef and pork products to a number of hotels, restaurants, fast-food chains, and food service distributors around the country.

But the dream of starting another family ranch never left his father, said Cobb, and in 1978, after nearly 20 years in New Mexico, S.G. and a business partner bought some land off a “longstanding ranching family,” in Lea County, where Hobbs is located. That family, too, was struggling with the economics of their chosen profession. “What happens with ranches is the families grow, but there’s not enough ranch income to feed everybody,” said Cobb. “So then they start selling it off.” For Cobb, raising cattle is still a family affair: His oldest son lives on the ranch and Sam comes out on weekends to help with branding, castrating, and corralling cattle. His granddaughter from Austin occasionally comes into town for workdays, too. The ranch, along with the family land in Texas, holds tremendous symbolic value to Cobb, whose father instructed him never to sell it.

After graduating from Texas Tech in 1976 with dual degrees in animal science and business, Cobb came back to New Mexico to work for his father at Rich Meat Services — first as a salesman, and then in operations. He had a knack for keeping clients happy by staying level-headed in a crisis. David Pyeatt, who was once a customer of Rich Meat Services, said, “Sam’s incredibly intelligent and witty as heck. And he always takes a complex problem and comes up with a very obvious and simple solution.” But the move away from sales may have been for the best; Pyeatt suggested that Cobb can be buttoned-up to the point of coming across as awkward. Tall, careful with words, and with near-perfect posture, Cobb sometimes has the air of a chaperone at a school dance. “When you first meet Sam, you may think he’s a turd, you know?” said Pyeatt, who, it must be said, considers Cobb a dear friend. “Am I saying that nicely?”

As a businessman, Cobb’s superpower is his pragmatism. In 1980, he took over RMS Foods as president, and the company soon became the largest supplier to Dairy Queen franchises in the Southwest. Years later, Cobb struck a deal with a Japanese trading company to export high-quality cuts of beef and pork to Japan — taking the company he inherited from his dad to new heights.

But he always had an eye on growing the business even more, and in the late ’90s, that meant looking beyond red meat. The company Boca Burger, started by a natural-food restaurateur in Boca Raton, Florida, was successful at capturing the public’s attention with a better-for-you veggie burger, at a moment when diet culture ran rampant. In 1995, then-president Bill Clinton made headlines for stocking Boca Burgers on Air Force One, after reportedly being introduced to the vegetarian product by a heart specialist. The trend caught Cobb’s attention, too.

In 1997, through a fortuitous chain of connections — and on the strength of his reputation as a meat purveyor — an invitation to join a group of investors and purchase Boca Burger came to Cobb’s desk. According to him, it was a no-brainer. RMS already had most of the necessary manufacturing equipment to get started. The titular Boca Burger — made primarily of soy protein concentrate and wheat gluten — essentially comes together using “the same manufacturing process as a ground-beef burger,” said Cobb. The only difference is the ingredients. “Instead of blending animal protein, we’re blending plant protein.”

Initially, Cobb became an employee of Boca Burger, sold off his Dairy Queen business, and ceased producing meat products at RMS Foods. When production of Boca Burger moved to Hobbs, RMS was manufacturing about 60 percent of the brand’s soy patties. “We started growing exponentially,” said Cobb, enough for the conglomerate Kraft Foods (now Kraft Heinz) to notice. Sales went from $20 million in 1998 to $40 million the following year. On the strength of that growth, Kraft bought Boca Burger in 2000 for an undisclosed amount. “I saw an opportunity in the plant-based category,” said Cobb, and it paid off. By 2002, Boca Burger sales reached $70 million.

After the 2005 fire, representatives from Kraft Foods visited Hobbs and were so impressed by Cobb’s operations that they decided to designate RMS the exclusive manufacturer of Boca Burgers. “Sam got a letter from Kraft telling him that,” said Barrientes, and the company president read it out loud to his staff in the newly rebuilt office conference room. His father stood beside him for the announcement. “They were in tears, because they were coming back,” said Barrientes.

Every morning Cobb is in the RMS office, he eats whatever plant-based product is being made at the moment for breakfast. It’s a daily ritual shared by many of the staff members, who sample the veggie patties all day to inspect the quality. The faux-meat burgers are good, employees admit, but of course, they aren’t … well, meat. (“I mean, I love my steaks,” said Barrientes.) Cobb isn’t planning on giving up meat anytime soon, and doesn’t expect others to immediately do so, either. “I’m an omnivore,” he said.

As a planet, we dedicate roughly half of all our habitable land to growing food. But the majority of that land — nearly 80 percent — is ultimately in service of raising livestock. That’s because livestock need pasture land to graze, but they also depend on animal feed — and growing enough corn and soy for all those farmed animals also takes a lot of land. Cattle and other ruminants pose a big problem for the planet in the form of greenhouse gas emissions; these animals have stomachs with multiple compartments, and their digestive process produces methane, which is then released when the animals burp. But the amount of land needed to raise animals for human consumption also means the global demand for meat drives a tremendous amount of deforestation and biodiversity loss. That’s why so many plant-based protein advocates argue mitigating the effects of the climate crisis rest on everyone eating less meat.

When it comes to matters of persuasion, however, Cobb understands that nobody has ever changed their diet unless they themselves wanted to. “I’ve got friends that wouldn’t put a plant-based burger in their mouth with a gun to their head,” he said. This awareness may be a business advantage for someone like Cobb — even if the uncomfortable truth may strike fear into the hearts of plant-based evangelists and climate advocates.

In the 2010s, Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods went all-in on developing veggie patties that supposedly tasted and bled like real beef. At the time, much of their messaging touched on the environmental case for swapping out beef for soy. “I know it sounds insane to replace a deeply entrenched, trillion-dollar-a-year global industry that’s been a part of human culture since the dawn of human civilization,” said Impossible Foods founder Pat Brown in a TEDMED talk, referring to animal agriculture. “But it has to be done.”

Amanda Edwards / Getty Images

The plant-based protein category enjoyed double-digit sales growth during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to data from the Good Food Institute, a think tank that tracks the alternative protein industry. But since 2022, demand for these products has been falling. For Brown and others, this style of practically pleading with consumers to change their habits spectacularly backfired. Beyond Meat’s stock price tanked by more than 99 percent in 2025 compared to five years prior. The company reported a net loss of $110.7 million in the fiscal third quarter of last year, its most recent earnings report. Its total outstanding debt is $1.2 billion. Beyond has never once turned an annual profit. There are a number of theories as to why Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods’ gamble on ultra-realistic fake meat failed so hard — including their inability to compete with beef on price and taste.

“Our thesis is that a bunch of products launched during the pandemic that weren’t ready for mainstream adoption,” said Caroline Cotto, head of NECTAR, an organization that runs taste tests with plant-based and animal-protein products in order to help the former achieve taste parity. “A lot of consumers tried those products and had a really negative experience because they were paying more for a product that didn’t deliver,” she added. “So they really soured on that category and have stopped revisiting it.”

Cotto argues that the plant-based meat industry is something of a “valley of disillusionment,” and it’s hard to disagree. This stunning market failure carries a lesson for the plant-based industry that the broader climate movement and environmental experts have long known: Information alone, even a lot of it, even the really dire stuff, is insufficient to lead to a change in how most people behave. Some industry leaders may now be actively running in the opposite direction of mentioning climate and sustainability: Peter McGuinness, the former CEO of Impossible Foods who stepped down last month, argues this sector struck out with consumers by becoming too “woke” and “partisan.” The future of Impossible, now, is cloudy. The company recently announced it is experimenting with protein-packed grains and pastas.

The plant-based burger category as a whole has slumped, and as a result, RMS is also producing fewer units of Boca Burgers these days. Barrientes estimates the plant makes less than 4 million pounds of soy-based burgers for Kraft Heinz every year, when in previous years, it was moving almost 20 million. Based on all his experiences in Hobbs, Cobb understands that part of selling plant-based food comes down to how you talk to people. “It’s the old adage. You can lead a horse to water, but you’re not making him drink,” he said. But he also reckons that the answer is simpler — that the role flavor plays cannot be understated. “If you want a hamburger, and you want a big old greasy hamburger, it’s hard to duplicate that with a plant-based product,” said Cobb. Cotto agrees — but thinks these product categories can achieve taste parity, or even become something consumers prefer over meat, with more research and development. “The biggest opportunity across the board is just making sure that these products taste great,” she said.

Cobb regularly goes out to eat with a small group of friends, including David Pyeatt, his former customer from his meat-supplier days. For someone in the food business, even casual meals can function as informal, but telling, focus groups.

At a dinner last October, when I asked the group whether they like faux-meat burgers, nervous laughter sputtered around the table. John, a rancher based in Hobbs, said there was nothing about “synthetic meat” that appealed to him, and said he didn’t think he would ever try it.

Pyeatt shared a story about how his wife had recently made two versions of sloppy Joes — one with ground beef, and another for his mother-in-law that used vegan crumbles from Boca. Pyeatt tried both, and loved the plant-based one more than the tried-and-true original. It simply, in his words, “tasted better.” But ultimately, he said, “if you put a steak in front of me, I’m going to like a nice steak.”

“Nobody here eats Boca Burger,” said Cobb, though his guests quickly contradicted that. Someone suggested that Boca Burger patties aren’t bad if served with a bit of mayo. The conversation underscored how, at the end of the day, people want to eat things that taste good — and the promise of something truly delicious can tempt even the staunchest meat-eaters among us. The servers began to bring out people’s orders, and when the last plate dropped, Cobb and his guests picked up their forks and knives and began to cut into their steak dinners.

Cobb believes the plant-based burger is functionally dead. Back at his office, speaking from behind his desk, he explained his view that faux-meat patties will never fully go away, but that demand is unlikely to return to the levels it reached during the pandemic.

Whether or not vegan brands should try to replicate the taste and texture of meat is “a really big debate right now in the space,” Cotto said. But breaking free of conventions set by meat-eaters and industrial animal agriculture will demand new ways of thinking, cooking, and dining. “We don’t have a name for it,” said Cotto, but the plant-based protein industry could also explore “a third-space product that’s sort of like — the closest equivalent I can think of is tofu, right? It’s a center-plate protein, but it’s not fitting into a narrow box for consumers.”

Whether or not plant-based brands will pursue that route, for now, remains to be seen. Either way, Cobb isn’t out of the game. When I asked him about the future of the industry, I was struck by his pragmatism. Ever the entrepreneur, he is still out looking for opportunities to bring in new plant-based manufacturing business. He argues that the concept of swapping veggies for meat could catch on “as long as it’s price competitive.” Last year, on top of its Boca Burger production, RMS began a new partnership with the Seattle-based Rebellyous Foods, a brand of plant-based chicken patties and nuggets that sells directly to food service and school districts. (Disclaimer: Former Grist CEO Brady Walkinshaw is an investor in Rebellyous Foods. He had no editorial role in this story.) The ingredients are nearly identical to those in Boca Burgers, employees told me, but the manufacturing process varies slightly, giving the faux chicken products a juicier, more delicious texture. Employees at RMS seem to love it: “It’s actually good stuff,” one told me.

Cobb said he’s interested in exploring the so-called emerging product category of “blended proteins” — think: sausages and hot dogs that replace some of their meat content with whole-cut veggies or soy. Plant-based advocates like these products because they help lower consumers’ overall meat consumption, even if they never give up meat entirely. But Cobb noted this practice is nothing new. “I used to put soy in hamburger patties. We used to do that for cost savings,” he said.

He reminded me that all of the technical equipment and expertise that RMS has acquired over the decades of being in the food-manufacturing business means the company is well-positioned to produce other vegetarian appetizers and snacks, like falafel. These, he reckons, can appeal to meat-eaters, as long as they taste good.

When it comes down to it, Cobb has been successful because he pays attention to what consumers want and, quite simply, makes it. When I asked Cobb if he would ever go back to processing meat, he answered: “I would if the opportunity presented itself and it created jobs for my employees and people in Hobbs.” He paused and added, “Yes, I’ve considered that.”