Photo: Eric Ch A few weeks ago, we told you about the contentious debate over the fate of a tiny fish known as menhaden. Meanwhile, a similar concern is quietly surfacing over several other varieties of small “forage fish” that live along the West Coast.

Photo: Eric Ch A few weeks ago, we told you about the contentious debate over the fate of a tiny fish known as menhaden. Meanwhile, a similar concern is quietly surfacing over several other varieties of small “forage fish” that live along the West Coast.

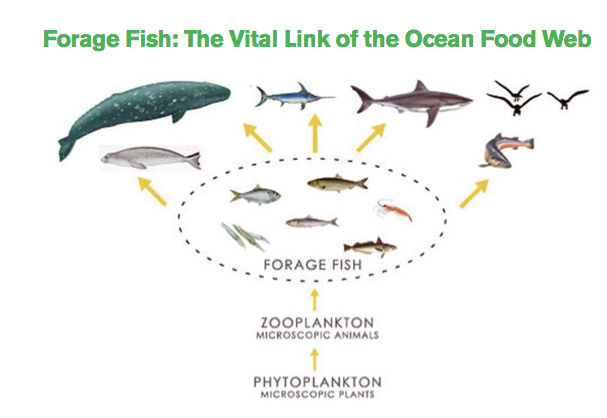

And by forage fish we don’t mean you’ll find them while walking in the woods. They are small fish — sardines, anchovy, mackerel, menhaden, squid — that serve as food to larger carnivorous fish. They’re the base of the food web, and are extremely important. When they start to disappear, then fish like salmon, halibut, etc. can suffer from malnutrition. In other words, without the strong presence of forage fish, the entire food chain is weakened. On the other hand, when forage fish populations are strong and vibrant, the same food chain can better withstand pressure from factors like climate change and ocean acidification.

That’s why, earlier this week, ocean conservation group Oceana sounded the alarm in a new report that points to gaps in the management of federal and state-level fisheries that have left important forage fish like Pacific sardines, hake, herring, market squid, and mackerel vulnerable to overharvesting.

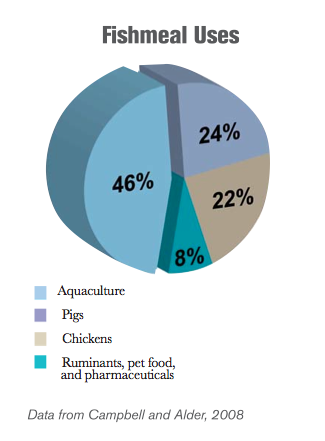

Campbell and Alder 2008“The story is the same as the menhaden’s,” says Geoff Shester, California program director for Oceana. “These are the critical forage species that provide the basis and foundation for the coastal economy. Given the huge demand for aquaculture feed, it’s only a matter of time before these fish become exploited as well.”

Campbell and Alder 2008“The story is the same as the menhaden’s,” says Geoff Shester, California program director for Oceana. “These are the critical forage species that provide the basis and foundation for the coastal economy. Given the huge demand for aquaculture feed, it’s only a matter of time before these fish become exploited as well.”

The Oceana report presents evidence suggesting that fisheries managers have not looked closely enough at how many forage fish need to be left in the ocean to ensure a healthy ecosystem. They add that aggressive harvesting rates (particularly for uses in aquaculture), have meant that species like Pacific sardines have been below sustainable levels for the past decade.

While squid, sardines, and other low-on-the-food chain seafood options are seen as a sustainable choice for consumers, they still need to be managed closely. And besides, says Shester, “Very few of the Pacific sardines are going to feed people directly, despite the fact that they’re extremely healthy, high in Omega-3s and are a low-contaminant seafood.” Instead, they’re being sold as bait for Japanese long-line fishing, or are being used as food in bluefin tuna ranches off the coasts of Mexico, Australia, and Japan.

Oceana timed the report to coincide with the Pacific Fishery Management Council’s (PFMC) meeting currently underway in Southern California. The conservation group is requesting the PFMC to revise sardine catch levels; and to prevent new commercial fisheries from developing that target unprotected forage fish like whitebait smelt, Pacific sandlance, and lanternfish. These last few are species you’ve probably never heard of, but like sardine sand menhaden, they play an important role in the marine ecosystem.

“A major [fish oil/meal-producing company] could come in today and start fishing them industrially because they’re not under a federal fishery management plan,” warns Shester.

And that’s not an empty threat. According to the Oceana report, aquaculture’s share of global fishmeal and fish oil consumption has more than doubled over the past decade. In 2008, 20.8 million tons of wild fish went into fishmeal and fish oil. While the feed ratio (the amount of ground up wild fish used to feed farmed fish) has improved, the fact is, the aquaculture sector is in rapid growth-mode, maintaining pressure on forage fish for the foreseeable future. Throw in the amount of fish meal used to feed pigs and poultry, and the harvest figures are daunting.

There’s also concern over the well-being of larger Pacific species — like Chinook salmon, albacore tuna, blue whales, sea lions, and California brown pelicans — which rely on foraged fish for their own nutrition.

Graphic: courstey of MFCNAsking for protection for a lesser-known fish population that’s yet to be commercialized — such as the Pacific lanternfish — is unusual, but it’s not unheard of. The PFMC implemented a coast-wide ban on the direct harvest of krill in 2006.

Graphic: courstey of MFCNAsking for protection for a lesser-known fish population that’s yet to be commercialized — such as the Pacific lanternfish — is unusual, but it’s not unheard of. The PFMC implemented a coast-wide ban on the direct harvest of krill in 2006.

As for the Pacific sardine population, PMFC chairman Dan Wolford says a preliminary assessment report showed the number of Pacific sardines have actually increased since last year. Exactly why it has increased or how much is still unclear, and will be examined by the committee.

“We’ll look not only at the biomass, but we’ll be looking at how much to set aside as the minimum threshold. It’s important to protect the ability of the fish to propagate successfully,” says Wolford. “I want to make sure everyone understand that forage [fish] is what makes the whole ecosystem work. It’s that portion of the food chain that changes plankton into food for major predators like salmon, groundfish, and tuna.”

But unlike the tussle over the future of the menhaden fishery on the East Coast (a conversation that can still be shaped by public comment until Nov. 9), there doesn’t seem to be much controversy over whether or not to protect Pacific forage fish. This fact might just be a sign that these important fish have begun earning some respect — and it’s point of pride for Wolford.

“The Pacific Council has a very good relationship with our fishermen. They’re involved in all the committees, and we listen to what they have to say. It’s part of our culture here.”