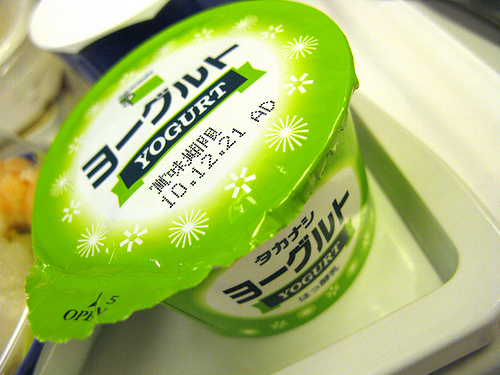

Photo by Frank Farm.

Here’s a superbly kept secret: You know all those dates you see on food products that say “sell by,” “use by,” and “best before”? Those dates do not indicate the safety of your food, and generally speaking, they’re not regulated.

I couldn’t believe it either, but a quick look at USDA’s food labeling site confirms that the only product for which “use-by” dates are federally regulated is infant formula. Beyond that, some states regulate dates for some products, but generally “use-by” and “best-by” dates are manufacturer suggestions for peak quality.

Suggestions. For peak quality. That’s all.

If this is news to you, you’re not alone. Research on date labeling in the U.K. by the organization WRAP shows that 45 to 49 percent of consumers misunderstand the meaning of the date labels, resulting in an enormous amount of prematurely discarded food. In fact, WRAP estimates that a full 20 percent of food waste is linked to date labeling confusion. Of course, that also means 20 percent more sales for manufacturers recommending those dates. After all, if your milk goes bad, you don’t stop drinking milk; you just go to the store and buy some more.

“Sell-by” dates are equally problematic. The goal of sell-by dates is to help stores stock and shelve their goods. Sell-by dates are designed to indicate a product is still fresh enough for a consumer to take it home and keep in their fridge for days or weeks. Most stores discard products as soon as they’re past their sell-by dates. It’s understandable. Many consumers would balk at buying something with an expired date, especially since they may not understand the date’s meaning.

But the cost of this waste is significant. In American Wasteland, a book that examines the massive quantities of food we waste from farm to fork, an industry expert estimates grocery stores discard $2,300 worth of “out-of-date” food goods each day. Even worse, the waste continues at home, since many consumers also misinterpret this date and discard products with weeks of good shelf life remaining. And all that adds up to a huge amount of wasted resources, with serious impacts to our land, air, and water.

The good news is that there’s a pretty straightforward solution to all this confusion and waste. It’s a system called “closed dating,” which uses a code to communicate information on product freshness to stores for stocking and shelving purposes without confusing consumers in the process.

As for the “use-by” and “best-by” sisters, there are two routes the system could take to reduce confusion and waste. Government could regulate dates more closely so that they serve as genuine indicators of food safety, as consumers already believe. But since the government can’t predict when you’ll accidentally leave your milk in a warm car for an hour, this can get tricky.

The alternative would be to eliminate the confusing array of dates completely and for consumers to once again rely on the wisdom of their senses to determine if food is edible. If that milk smells rotten, by all means throw it away. But if it smells like good milk and tastes like good milk, it makes little sense to pour it down the drain because the manufacturer has suggested to you that it’s bad. In fact, when was the last time you heard of someone actually drinking bad milk and getting sick?

There are, of course, options in between — government regulation of some items and no dates on others; no regulation but increased education around the current system; or simply teaching people about safe food.

Once you’re over the shock of not having to throw out that perfectly good yogurt, let me know: What do you think?

A version of this post originally appeared on Switchboard, the blog of the Natural Resources Defense Council.