This piece started out as a confident prescription for California’s drought ills. But when I began writing, I kept coming across things that seemed confusing or contradictory. And each time I went to the experts to clarify, they’d explode all my basic assumptions.

So instead of writing that piece, here’s a list of all the (misguided) conventional wisdom I had absorbed set right — or, at least, clarified.

California hasn’t forced agriculture to cut water use: A myth

Californians just don’t want to be suckers. When Gov. Jerry Brown told the state to cut back water use by 25 percent, he didn’t mention agriculture, and that made people suspicious. It looked to a lot of people like farms were getting a free pass. They (reasonably) thought, I don’t want to be a dupe and scrimp and save if agriculture isn’t doing the same.

So why didn’t California also demand that ag cut back?

It actually did, said Doug Parker, director of the University of California Institute of Water Resources. Brown just didn’t talk about that when he made his big announcement (he’s probably kicking himself about that). Growers that rely on the State Water Project are taking an 80 percent cut from their normal water share. Central Valley farmers who draw from the federal system of dams and canals have taken a 100 percent cut. Brown may be going back for further restrictions.

When farmers get these cuts, they cope by pumping groundwater (which is causing problems in some places — more on this later), or buying water from people with senior water rights. But ultimately, cuts in water deliveries lead to cuts in water use. California farmers took about 5 percent of their land out of production last year, and that number will surely go up this year.

Agriculture uses 80 percent of California’s water: Not the whole picture

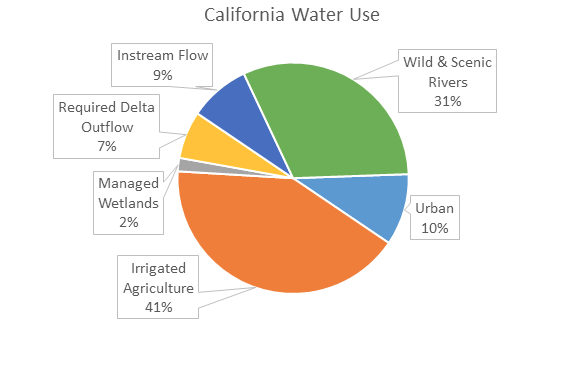

This isn’t exactly wrong, but it’s useful to understand the nuance. Here’s how water is divvied up in California:

Northern California Water Association

You do get farmers using 80 percent of water and cities using 20 percent if you don’t count the other pieces of the pie. But those pieces are important, and by no means guaranteed! We are using that water to create habitat and beauty, to allow lots of species to thrive. Leave that out of the equation and it’s easy to forget about the environment and the human joy that comes with rivers. And in dry years like this, the percentage dedicated to the environment isn’t enough for some species: Biologists are worried about salmon, and the delta smelt are on permanent life support.

Dumb laws prevent the buying and selling of water: Not true any more

This was one of the conclusions of my last piece on the drought. And that was true … back in the 1970s. Back then, if you had rights to water, you had to use it or lose it, said Parker. So if you had senior water rights for a patch of rocky desert land, unsuited to growing anything, you still had an incentive to use as much of your water as you could. But that rule changed around 1980. Now, you can take that water and sell it to a city, or a farmer with great soil but little water.

This is confusing — I’d assumed that farmers were slow to adopt water conservation practices because they had cheap water from senior rights. After all, between 40 and 50 percent of farm irrigation in California is flood irrigation: You generally use little sections of curved pipe to siphon water out of a ditch, and flood the furrows between the rows of plants.

Flood irrigation in Arizona.NRCS

This seems wasteful, and indeed it requires a lot more water than drip irrigation. I thought that a market for water would drive otherwise wasteful farmers to adopt better techniques — but that reasoning relied on another incorrect assumption.

Farmers are wasting a lot of water: A myth

Um, not really, said Ellen Hanak, director of the Water Policy Center at the Public Policy Institute of California.

“But let’s say I’m a farmer down in the Imperial Valley,” I said. “I’ve got senior water rights from the Colorado River, and I’ve always used flood irrigation. Now that I can sell my water on the market, shouldn’t I be installing drip irrigation? I’d use a lot less water to grow my lettuce, and I could sell the rest. I make money, there’s more water to go around, everyone wins.”

“You can’t do that,” Hanak said. “Not allowed.”

“Why not?”

Well, basically because flood irrigation is not nearly as wasteful as it looks. Yes, it takes a lot more water than other forms of irrigation, but all that extra water goes somewhere: It seeps into the ground and restores aquifers, or it flows out of the field and back into the river. So, if I sell all my water, it suddenly deprives my neighbors of my backwash, which they’ve come to rely on. Therefore, the law doesn’t allow me to sell that portion that historically passed through my field and then continued on downstream, or underground.

Aha! I thought. So this is the dumb law causing the market to fail! Get rid of this obstacle, and farmers will adopt more efficient practices, leaving us with plenty of water, right?

Wrong, Hanak said. That’s another misconception.

Farm conservation measures can free up plenty of water: One last myth

Switching from flood irrigation to a more efficient system like drip does improve water quality. And you lose less water to evaporation — but just a little bit. You can see how this works in this infographic from the Pacific Institute (don’t pay too much attention to the specific numbers, they are just rough placeholders).

The thing to pay attention to here is that the “more efficient water use” scenario, while it keeps mud and salts out of the river, doesn’t save much more water in the end.

“It’s a very small percentage lost to evaporation,” Hanak said. And in the real world, farmers actually end up using more water when they switch to efficient irrigation, she said. That’s because upgrading irrigation boosts yields: Tomatoes have been setting yield per acre records every year, because farmers have come up with better techniques based on drip irrigation. You can see the same thing going on with onions, bell peppers, and cotton. With flood irrigation, water flows through farms. With drip irrigation farmers can capture more of that water and grow more food.

The end result: Irrigation upgrades increase farm productivity and profits, but also tend to increase the farm’s net water use. “Irrigation efficiency doesn’t save water for the system as a whole,” Hanak said — blowing my mind.

OK, now I know nothing. What is water even for?

Assumptions are useful things — they provide a foundation for understanding the world. The more I read and talked to experts, the less of that foundation I had left, and I found myself asking the most basic question: What is water for?

Well, it’s for drinking. That’s pretty important.

It’s for growing food — at least a bare minimum to feed ourselves.

After that, keeping fish alive and ecosystems healthy is a priority — at least for me.

But even in this historic drought, California has plenty of water left over after those uses. So then we move up the hierarchy of needs to things like lawns and golf courses, and farming as a business (beyond the subsistence level). Hey, we have some of the best growing conditions in the world; maybe we should use the rest of this water to stimulate our economy and export food like almonds.

That’s basically the way that water is divided up at this point. As climate change reduces the water stored in the snowpack, and as populations grow, there will be less water to go around. The system is already under enormous pressure — there’s not going to be a solution that will make everyone happy.

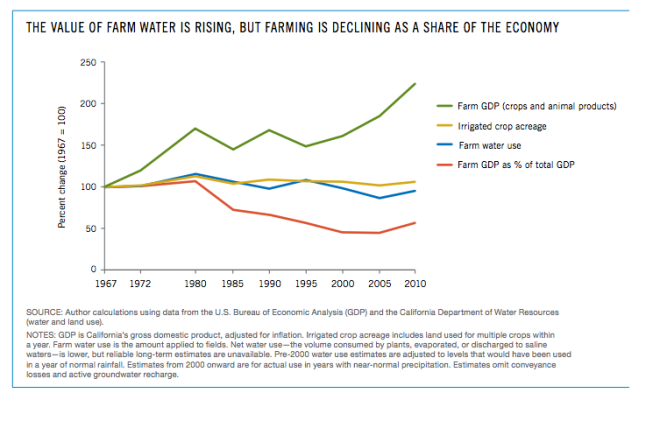

The least societally important, and least profitable use of water, I suspect, will be farming. Cities will expand, and farms will shrink. We already see that shift happening. Since 2000, farm water use has declined. A lot of that decline comes from farmers taking marginal land out of production, Hanak told me. At the same time, farm income is up: Farmers can afford to give up land because they are planting higher-value crops (like almonds) on the rest of their acreage.

What then do we do?

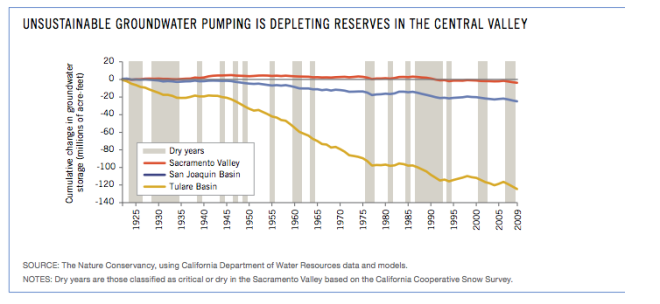

Most places in California have plenty of water to keep humans alive. But, there are neighborhoods in agricultural areas that have lost their drinking water because farmers with deep straws have sucked the wells dry. Some people are beginning to suffer from this classic example of the tragedy of the commons. And it’s always the poor who suffer most.

My first reaction is to look for forceful solutions: Perhaps local governments could stop giving permits to drill wells in sensitive areas. Some are trying to do that, though it can backfire, and may not hold up in court.

People like to seek villains by pointing at almonds or alfalfa (to feed cattle), but it would be nearly impossible to change water use by telling farmers what they can and can’t plant.

“We will be in court arguing for decades if we try to regulate where crops are grown,” said Renata Brillinger, executive director of the California Climate and Agriculture Network, speaking on a panel about farming in California’s drought put on by the Berkeley Food Institute.

It seems self-evident to me that society has an urgent duty to take care of people who lose their water. But when it comes to fixing the systemic problem, it’s probably better to be patient. California communities have to set groundwater management rules by 2020. This is ridiculously late — think of all the expense and strife we could have saved if we had started managing groundwater 20 years ago. But we seem capable of making hard decisions only when we have no other choice — the challenge is to make thoughtful decisions, rather than panicked ones that we’ll regret.

The legislature could have imposed rules from above that would be in place now, but lawmakers wanted to allow the people to craft rules that were contextually appropriate. That seems wise to me. It doesn’t make sense to implement the law overnight, Hanak told me, but it would be in the best interest of many farm communities to make rules sooner rather than later — so they don’t have to wait until 2020.

Meanwhile, we should still be pushing water-conservation practices. Even if irrigation efficiency doesn’t add water to the system, it does clean up the environment, while making California’s farm economy more resilient to climate change.

Instead of taking a reductive approach and looking for a simple evil to vanquish, Brillinger said, we have to understand the system and, as Wendell Berry put it, solve for pattern. Instead of trying to solve problems with centralized, top-down control, we need rules informed by local knowledge and crafted by local water users. Instead of focusing only on big technological solutions, like desalinization plants and dams, we need to look for small-scale and biological solutions, she said. The “only” there is key: The big engineering projects could really help in the crunch times, but they’re not going to make this problem go away.

Humans faced with a crisis want to find a villain, pick a fight, and exercise quick, top-down action to bring the accused to justice. This kind of thinking may make sense in a small tribe, but it’s all wrong for a complex societal problem like California’s drought. It’s especially hard to avoid this reductive thinking when conventional wisdom is peppered with misconceptions. California may be getting drier, but we’re still awash in water myths.