USDA photo by Keith WestonEven the best conservation measures could be thwarted by severe weather leading to floods like this one in North Dakota, 2013

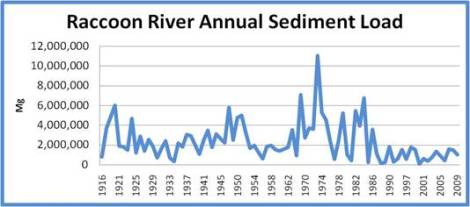

While I was in Iowa recently, Chris Jones, an environmental scientist at the Iowa Soybean Association, showed me this fascinating graph (based on this study). It basically shows how much dirt was in one of the main rivers flowing through Iowa’s farmland over the last century:

It doesn’t look like much at first, but becomes more and more interesting as you study it. Because the span of time here is so long (1916 to 2009) and because changes in agricultural policy have had a big effect on the erosion of topsoil into rivers, you can see historical events reflected in these numbers.

That big peak in 1973? That came just after Earl Butz, then the secretary of agriculture, urged farmers to plant fencerow to fencerow. Farmers cut into marginal land, and then heavy rains followed in Iowa. The newly disturbed soil washed off the fields and into the rivers, creating the spike on the graph.

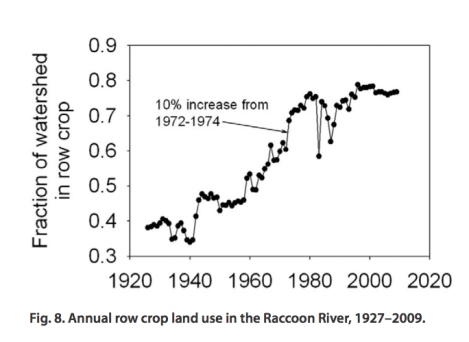

In the 1980s things were volatile: During the farm crisis, land went out of production, then was planted again. If you compare the graph above with the one below, you’ll find a correlation between land going into row crops and erosion.

As you can see, farmland has leveled out at about 75 percent. But erosion has gone down. The most interesting part of that first graph, to me, is the far right-hand side: There’s been less topsoil washing down the Raccoon River in the last two decades than at any other time. Or at least any other time on this record: If you go back before European settlement, there was very little erosion on the prairie. But still, for the period in which anyone was farming, the modern farmers look like the best stewards; the year with the lowest recorded sediment loss was 2000.

I was curious: Is this emblematic? Is my whole conception of modern agriculture as an environmental catastrophe out of date?

Well, it depends where you look. The Raccoon River watershed is doing better, but other places are doing much worse. Scientists at Iowa State measured erosion by looking closely at the layers of mud in the bottoms of some of the state’s lakes. And they concluded that, overall, more soil is washing away every year.

There may be a way to square these seemingly contradictory studies, Jones suggested. A lot of the dirt that ends up at the bottom of lakes could have come from stream banks, rather than fields, he said. As agriculture has intensified, the creeks have been straightened from meandering rills to steep-banked culverts in many places. Those older crooked creeks would move sediment just a short way before catching it, sometimes for years, behind a beaver dam, or in an oxbow. Now, it’s a pretty straight shot for dirt to get from field to lake.

When you look at other ways of measuring environmental progress, you can see a similar picture: There has been a modest reduction in the amount of nitrogen fertilizer that ends up in the Iowa River (which is where the Raccoon River goes). But, at the end of the pipe, when all that water flows out of the Mississippi River and down into the Gulf of Mexico, things are still getting worse. The main culprit is the Missouri River, which drains much of the Corn Belt and had a 43 percent increase in nitrate pollution between 2000 and 2010.

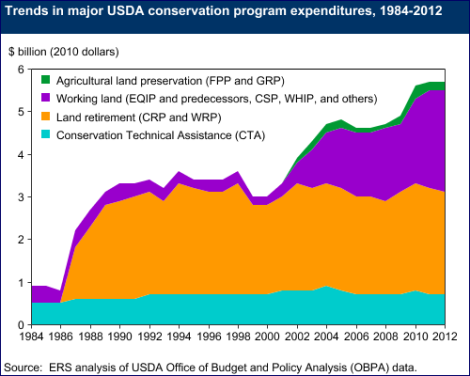

The U.S. government has been spending billions every year trying to improve agricultural conservation. And it’s really making a difference in places like the Raccoon River watershed. But in other places, booming corn prices have led some farmers to plant fencerow to fencerow once again.

And then there’s the weather. A huge part of the erosion and water pollution that occurs each year can be traced back to one or two big storms — gully washers that rut fields. And we are seeing more of these big weather events, as abnormal becomes the new normal. “We claim improvement in a dry year, and then the sky is falling in a wet year,” said Keith Schilling at the Iowa Geological and Water Survey, who co-wrote the Raccoon River study that got my attention.

So, while we should give credit and encouragement where it’s due, in sum we’re still polluting with our food system.

What’s the solution? In a word, plants: Plants sheltering the earth during the big storms; plants slowing raindrops with their leaves; plants holding down the earth with their roots. In places, people have begun to restore critical sections of the old prairie. There was once 167 million acres of tall-grass prairie in the land where we now grow corn and soybeans, and less than .1 percent of that prairie remains.

When I asked Eugene Turner, a professor at Louisiana State University, about this, he sent me the Marsden Farm study, which offers a potential way to mimic the prairie while still turning a profit. Researchers mixed things up by adding some grasses into the usual rotation of corn and soy.

Successful demonstration projects like this are sometimes hard to scale — it’s a lot easier to get results when you have a team of researchers scrutinizing the fields than if you are just one farmer trying to figure it out as you go along. And in recent years farmers have been pushed by a strong market incentive to just plant as much corn as possible. But as corn prices come down, perhaps more farms will look for alternative methods.