Jen Jones

A few years ago, Rebecca Thistlethwaite and her husband were working 80 hours a week running a large pastured meat and egg operation called TLC Ranch on rented land. The couple had spent six years barely making ends meet. They wanted to buy their own ranch, but the cost of land in Monterey County, Calif., was astronomical. Getting their meat processed presented several challenges (as it does for many small producers) and many of their loyal customers were cutting back on local and ethically produced food after the economic downturn. So, the couple decided to sell the farm and throw in the towel. Kind of.

In October of 2010, Thistlethwaite wrote on her blog Honest Meat:

… we are off to live in an RV for the next couple years, volunteer on farms and ranches around the country that we admire and hope to learn from, write a little blog about our adventure, and have some fun too.

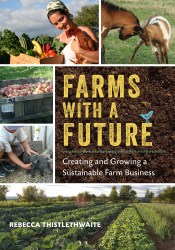

And that’s exactly what they did. The result of this adventure is Thistlethwaite’s new book, Farms with a Future: Creating and Growing a Sustainable Farm Business. As she sees it, the book is a “practical, accessible guide that doesn’t sugarcoat the challenges of farming, but gives people some good ideas.” It’s chock full of concrete suggestions based on Thistlethwaite’s year of research and observation, the kind of book you write precisely because you need just such a guide yourself but can’t find it anywhere. And it will probably help a lot of young farmers. It might also dissuade some from jumping headfirst into a business that is not for the faint of heart — but Thistlethwaite is fine with that.

We spoke with Thistlethwaite recently about the book, the journey, and the farm she hopes to start next.

Q. Do you want to talk a little about why you and your husband chose to sell your ranch?

A. We decided to take a break because we felt like the conditions under which we were operating were just not conducive to running a successful farm. We were paying some of the highest land rent in the country. And we were leasing land, so we really never knew what was going to happen the following year. We were also living in an area with a lot of crime. We had animals and equipment stolen; that made it really hard to run a business.

We didn’t want to quit farming, but we wanted to change where and how we were going to do it. So we thought we’d learn about how other farming operations around the country were doing it, how they are grafting together sustainable business models that meet their quality-of-life goals while being good for the earth and economically viable. It was a way to get inspired and learn. And it was a much-needed vacation!

We visited and interviewed about 19 farms total. And I think 14 of them ended up in our book.

Q. And where did you end up after the trip?

A. Now we’re located in the Columbia River Gorge on the Washington side.

Q. Do you want to speak about the challenge you and the farmers you visited face when it comes to conveying the value of sustainably produced food?

A. With the contraction of the economy, consumers are actually looking for more than cheap food. They’re looking for something that is affordable, but also embodies their other values — whether it be environmental values, social values, or the value of supporting their local economy.

So even if you’re a wholesale farmer, I think it’s really important to get your brand and your values across to your eventual customers. To just be an anonymous farmer producing an anonymous commodity doesn’t give you a chance to let your customers know who you are and what your story is. Telling that story and getting it all the way to the end user is really important. And you will be rewarded if it’s done right.

Q. You write: “The further you get from your consumer the more likely various certifications will become necessary.” Say more.

A. If you’re selling to the end user, it’s really easy to verbally express your values, to let your customers visit your farm, and take pictures, etc. A friend of mine, Joe Morris, calls it “first-person certified.” The person who’s consuming it is basically certifying that it meets their values.

For the most part consumers are looking to a certification that says you are doing what you say you’re doing. Although they’re not perfect, they’re much better than using meaningless words like “natural.” Getting certified organic or Food Alliance certified is basically saying that you’re willing to spend money on having a third-party auditor come out to your farm and verify that what you’re saying you’re doing is correct. And of course there are opportunities to cheat, and to make your farm look really good the day your certifier comes out. But for the most part the system works pretty well.

Q. In my experience, even the farmers who charge what seems like a lot for their food aren’t making an amazing living. Did you meet anyone over the course of the year who was doing better than you’d expect for a farmer?

A. Yes, there were several farmers who started with limited, “normal” means, who are doing really well. Butterworks Farm in Vermont is one good example. The owners started out with $10,000-15,000 in loans. They were the first organic dairy in Vermont. They have built all kinds of infrastructure in their farm using operating capital. They haven’t gone out and taken on a lot of debt and that has served them well.

Then there was Renard Turner of Vanguard Ranch. He’s finishing [grazing] 100 goats a year, but because he’s selling the meat as value-added products — goat kabobs, goat curries, etc. — his average earning is $38 a pound. His wife’s not able to quit her day job yet, but he’s able to cover all his operating expenses and pay himself an income.

None of these people are going to retire to the Caribbean or anything. But just being able to cover your operating expenses and pay yourself in some way — whether that’s a salary or an owner’s draw or just building equity in the business that you’ll eventually sell — is important. We never paid ourselves an income, but we were building equity and when we sold our business we discovered all that equity we hadn’t really kept track of. And we did amazingly well. Now we have the opportunity to farm again, because we actually have the money to buy land. We haven’t found the right piece of land yet, but we’re looking.

Q. Do you want to raise animals again?

A. Yes, although if we own our own land, we want to do something much more diversified, including perennial crops like fruit and nut trees, along with animals and grains. We’re thinking about a full-diet CSA model.

Q. It sounds like you’re going to run a very different business than the last one.

A. This process taught me a ton. I think our next business is going to be a lot more sustainable and meet our quality of life needs. First we found an area we love. We also want to create a much smaller business model. We’re hoping to create more of a neighborhood-oriented CSA, and even do some bartering. (We have neighbors across the street who make wine, for instance — and I’d be happy to barter with them all day long.)

We also have access to enough acreage out here to grow our own [animal] feed, which to us is a really important part of sustainability and of controlling the cost. It’s not always the case that growing feed is cost effective, but land is so cheap and water is available and cheap, and we can borrow equipment here too, because there’s so much grain grown in this area.

Q. It almost seems like the biggest factor is picking the right location.

A. Our trip around the country was also about looking for that right spot. We hope we’ve found it.

Q. Are there any models or kinds of farms that just don’t work right now?

A. With the price of feed this last year, almost everyone I’ve talked to who is a commodity meat farmer is losing money. And some operations are hemorrhaging really badly, like conventional dairies.

There’s an important difference between what I call a “price taker” and a “price maker.” If you’re always subject to the vagaries of the market, then some big meat packer or commodity grain buyer has already pre-sold your product before you’ve even produced it. Those people are hurting. The people who are setting their own prices are doing much better.

Q. Do you want to name some farms you think more of us should know about?

A. A lot of the farms we feature in the book are doing amazing work and should get more notoriety. Like Misty Brook Farm in Massachusetts. They had the best raw milk I’ve ever had in my life.

Bluebird Grain Farms is growing Old World grain varieties that have less gluten than most grains, and they’re making freshly milled flour (they basically mill it to order). Crown S Ranch — outside Seattle — is using the Joel Salatin model. They’re layering six or seven animal species across the land and then they’re also growing all their own seed and hay. They built an on-farm store. They’re also doing agrotourism and calling it “haycation.” They’ve converted an old cabin into a cute little one-bedroom rental. I also love Greg Massa’s work. He’s probably the only rice farmer in the country who sells at farmers markets. Most commodity grain farmers couldn’t fathom making a living by direct-marketing their grains, but he’s proving it’s possible, and he’s diversified with animals and almonds.

All of these farms are really amazing operations. But they all face challenges too.