Picking a fight has always been a surefire way of getting attention. Whether it’s on a schoolyard, or in the national media, conflict changes the center of gravity and attracts a circle of onlookers. For journalists, this incentive to be pugnacious is powerful — but sometimes the urge to scrap overwhelms substance and fairness.

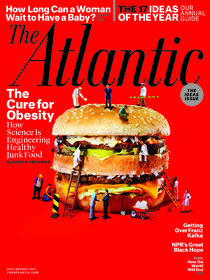

That’s what happens in David H. Freedman’s 10,000-word cover story for this month’s Atlantic: “How Junk Food Can End Obesity.”

Freedman’s story has one good argument. The bulk of the media conversation about nutrition has been about how to help the privileged healthy be healthier. Freedman argues (persuasively, I think) that we need to focus more on fighting obesity where it strikes hardest: among the poor. So, he says, let’s do some jujitsu with the food-processing and mind-control tricks that Big Food uses to get us to eat more, and instead use those tricks to get people to eat less.

Freedman’s story has one good argument. The bulk of the media conversation about nutrition has been about how to help the privileged healthy be healthier. Freedman argues (persuasively, I think) that we need to focus more on fighting obesity where it strikes hardest: among the poor. So, he says, let’s do some jujitsu with the food-processing and mind-control tricks that Big Food uses to get us to eat more, and instead use those tricks to get people to eat less.

That point alone is enough for a provocative article of maybe 4,000 words. In fact, I recommend that you do what Freedman’s editor should have done — trim his piece down and just read its third section: “The Food Revolution We Need.”

The rest of the piece — well, it just gets weird. Freedman uses his remaining 6,000 words to build some very tortured logic accusing “the Pollanites” — meaning those influenced by Michael Pollan to seek out “wholesome” food — of thwarting this healthier-junk-food revolution by failing to eat their share of Big Macs and McMuffins.

This would make a great satire. It doesn’t work so well as a straight argument.

A quick disclaimer here, because I have connections on both sides: I’m a Pollanite (or PollaNate, if you like). I studied with Pollan and I think of him as a mentor. I also know Freedman. I’ve been impressed with things he’s written in the past and I let him know it.

When I told Freedman that he hadn’t convinced me that I and my fellow Pollanites were responsible for McDonald’s failure to make healthy food, he conceded that this was the weakest part of his argument.

Here’s how that argument plays out:

Step one: We’ve attacked the fast food industry until it’s begun to motivate change, which is good. Fast food restaurants are trimming 100 calories here, 50 calories there, and that could make a big difference in the long run.

Step two: But now, activism against fast food has become too successful, causing health-conscious folks to abandon junk food completely.

Step three: Without the health-conscious middle class buying fast food, McDonalds will have no incentive to make its fare healthier.

Step four: Therefore, if you care about the poor, buy a Big Mac!

And it’s not enough to buy fast food, we need to praise it too. Freedman correctly points out that we Pollanites tend to ridicule attempts at healthy fast food, like the McLean, because we don’t trust that the junk-food industry really can produce something salutary. Even if I accept the contention that fast food can be healthy in some limited way, I’d still object to the characterization of the industry that’s implied. Freedman would have us believe that the fast food industry is like a delicate orchid, that needs to be prodded and coddled in just the right way in order to provide this flowering of healthy processed food.

I’d like to offer a humble alternative:

Step one: We’ve attacked the fast food industry until it’s begun to motivate change, which is good.

Step two: As health-conscious folks abandon junk food completely, it just ups the pressure.

Step three: McDonald’s realizes it is on the wrong side of history, and tries to make healthier food to avoid complete demonization.

Step four: Therefore, if you care about the poor, don’t buy a Big Mac.

I don’t know, that seems simpler to me.

Too often, Freedman argues with crude misrepresentations of Pollan’s positions. For instance, he says that wholesome-food devotees are sometimes fooling themselves, making whole foods unhealthy by piling bacon, butter, and clotted cream atop our chard, and that some have an unscientific fear of chemicals in food.

Both are true, but it’s unfair to tar all Pollanites with this brush.

The real Pollan has, indeed, made broad statements urging people to, for example, “eat food,” as opposed to highly processed “edible food-like substances.” But he hasn’t ever said that all processed food is evil, or that we only have processed food to blame for our nutrition problems.

Move past all the straw-man-handling and just one question remains: Is avoiding processed food a sound health strategy?

Pollan says yes. Freedman says no. Or wait, Freedman’s “no” is contingent on our ability to find processed food that’s actually healthy:

To be sure, many of Big Food’s most popular products are loaded with appalling amounts of fat and sugar and other problem carbs (as well as salt), and the plentitude of these ingredients, exacerbated by large portion sizes, has clearly helped foment the obesity crisis. It’s hard to find anyone anywhere who disagrees.

Pollan, on the other hand, is explicit: He counsels against eating processed foods because they tend to be stripped of fiber and packed with fat, sugar, and salt. Warning people away from highly processed food is reasonable as long as the bulk of highly processed foods continues to be unhealthy.

Food processing, at its most basic level, increases the bioavailability of nutrients. Processing food (cooking it, chopping it up, grinding it to mush) allows our bodies to absorb more calories from every bite. Among women eating a totally raw diet in one study, half lost so much weight that they stopped menstruating. Food companies add salt, fat, and sugar to their products because all act as preservatives at high levels, and all help food that’s lost its freshness taste better. The result is a frequently unhealthy mix of ingredients that shoot into the bloodstream as if injected.

I’m all for experimenting with fast food to make it healthier. But there’s a real chance it won’t work. Other efforts to engineer healthier food have failed (trans-fat margarine, anyone?). Nutrition science is bogglingly complex, and in many ways, we really don’t know what we are doing.

If you want a truly great read, skip Freedman’s piece and check out this inquiry into the cause of the obesity epidemic. The writer, David Berreby, points out that it’s not just humans who have been getting fat:

over the past 20 years or more, as the American people were getting fatter, so were America’s marmosets. As were laboratory macaques, chimpanzees, vervet monkeys and mice, as well as domestic dogs, domestic cats, and domestic and feral rats from both rural and urban areas. In fact, the researchers examined records on those eight species and found that average weight for every one had increased. The marmosets gained an average of nine per cent per decade. Lab mice gained about 11 per cent per decade. Chimps, for some reason, are doing especially badly: their average body weight had risen 35 per cent per decade.

We don’t know what’s going on here. When dealing with the mysteries of nutrition, we have to act with humility. And attacking Pollanites for views that Pollan himself doesn’t hold — while it may draw a crowd — is anything but humble.