Whole Foods has long graded its food for its environmental and social impact. But it turns out that many organic farmers don’t like this grading system. Now a group of those farmers is protesting. In a letter to Whole Foods CEO John Mackey, they said that it costs farmers too much to get graded, and that the system has major flaws.

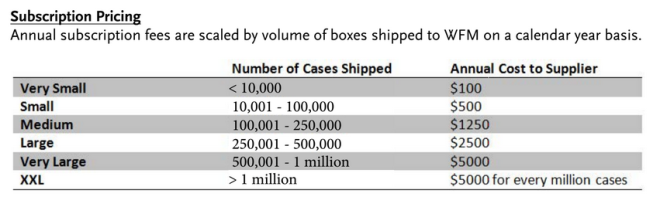

Tom Willey, one of the elders of the organic movement and a signer of that letter, told me that farmers have to pay Whole Foods to participate in the grading scheme: There’s a fee to get in, and then an annual fee. Farmers must also buy a barcode printer and register every crop variety with a barcode standards organization — which means more fees. All this is impossible for small family farmers with tight margins, he said.

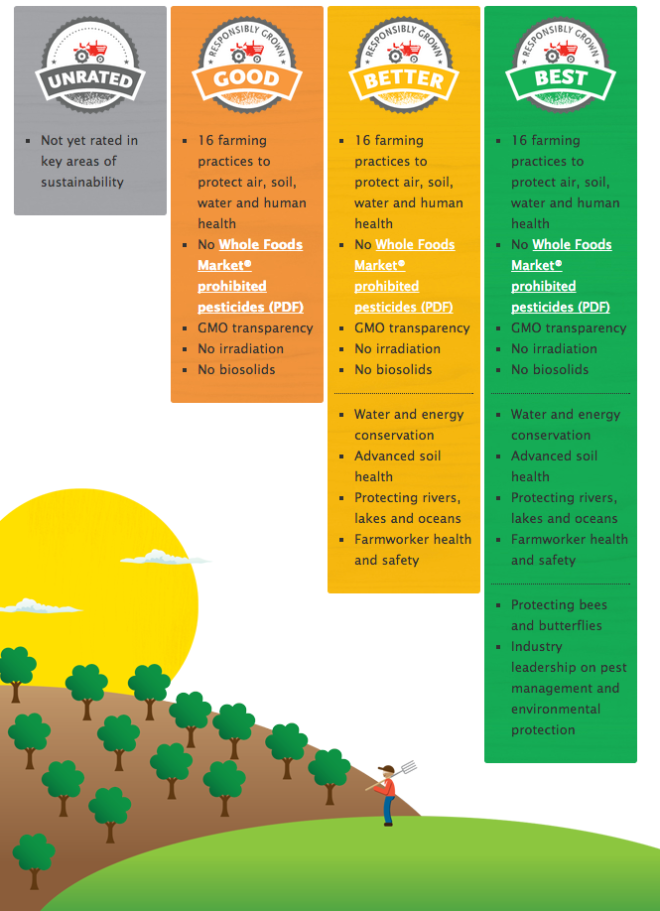

From the Whole Foods Market “Responsibly Grown” manual

And the system itself is flawed, Willey said. One farmer in Vermont lost points for failing to conserve water as much as he could — but he lives in an area so wet that he has to pump water off his land every year.

Farmers’ frustration with the Whole Foods system is longstanding, he said: “We were just twisting in the wind behind the bushes because everyone is scared of risking their sales to Whole Foods.” Finally, a few farmers decided they needed to say something, leading to this letter.

NPR’s Dan Charles got this response from Matt Rogers, a global produce coordinator for Whole Foods:

Rogers, for his part, insists that Whole Foods is not backing away from its support for organic farming. He says the new ratings are simply a way to talk to farmers and customers about things that the organic rules just don’t touch, “such as water conservation, energy use in agriculture, farm worker welfare, waste management.”

There are farmers who are doing a great job with that, he says, and they aren’t all organic. “There are conventional growers that we work with who are incredible stewards of the land, who do a tremendous job with their workforce, who deserve to be recognized,” Rogers says.

The problem with certification, whether it’s for organic produce or anything else, is that it’s very hard, once you put a system in place, to get it to adapt to new issues. I recently wrote about Scott Poynton, of The Forest Trust, who has laid out an argument pointing to these limitations in a book-length essay. Some farmers are forgoing organic certification because they find it too cumbersome, and they think they can actually have a better environmental impact if they have access to a full range of tools, not just those allowed under organic standards.

It was Mark Bittman who first alerted me to this issue in his fantastic 2012 article on California’s Central Valley. In that article he encounters lapsed organic farmer Paul Buxman:

Paul Buxman … has become gradually disillusioned with organics … after a few years, Buxman came to believe that nonorganic chemicals can target problems more precisely and more accurately than organic ones and that it was time to leave “organic” behind. “An organic pesticide is still poisonous,” he told me, over his fabulous biscuits, served with his (ditto) apricot jam.

I hope Whole Foods takes this complaint seriously (and looks to Poynton for some ideas on improving the sustainability of its supply chain), while working to reduce the burden it places on farmers. At the same time, I hope the store keeps pushing forward: Let’s focus on what’s healthiest for eaters, farmworkers, and the environment, not on the arbitrary and unscientific distinction between those toxic agrichemicals made by people, and those toxic agrichemicals made by plants — then refined, in a factory, by people.