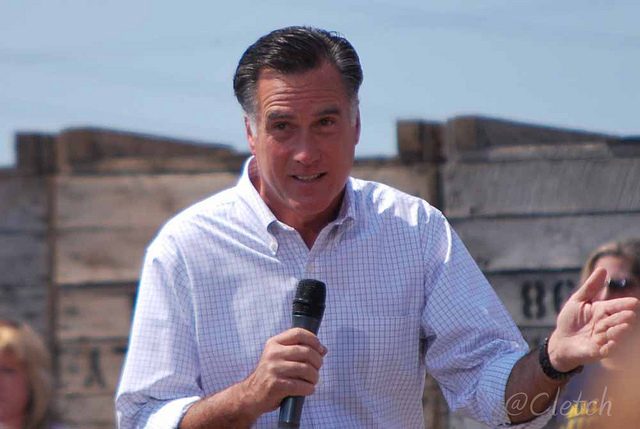

Pat WilliamsRomney speaks at a rally on a Michigan farm.

Here we are, less than four weeks away from the election, and Mitt Romney finally has something to say about food and farming. Sort of.

In a white paper released Tuesday called “Agricultural Prosperity: Mitt Romney’s vision for a vibrant rural America,” the presidential candidate and his advisers outlined their farm agenda. But the 16-page document talks very little about actual farming; instead it uses agriculture as a lens on Romney’s preexisting tax, trade, regulation, and energy platforms. (For the record, that would be: less, more, less, and ethanol). He also promises to “strengthen our nation’s rural communities,” and “ensure that a strong farm bill is passed in a timely manner.” (This last part is especially amusing, considering the last farm bill actually expired on Sept. 30.) So … timely? No longer possible.

Romney also plays up the “family farm” element throughout, with nostalgic odes like this:

… it is not only our core values that thrive in our small towns and family farms; our economy does as well, when hardworking men and women are supported by sound policies that promote growth while minimizing unnecessary interference from Washington bureaucrats.

Translation? Romney wants to do away with the estate tax. “Inheritance plays such an important role in the preservation of family farms, tax policy can make an enormous difference in the prosperity or struggles of rural America,” the paper reads.

Obama has proposed changing the tax to a 45 percent tax rate on individual estates that are worth more than $3.5 million — down from the current $5.2 million. But at that level, Obama spokesperson Ben LaBolt told the Des Moines Register, “99.7 percent of all estates would be exempted, and just 60 small farms and businesses in the entire country would be affected.”

On the regulation front, the paper zeroes in on what it calls “overzealous efforts” to extend the Clean Water Act, the recently defeated child labor rules (which the white paper claims “would bar teenagers from working on their family farms,” but, in fact, included a parental exemption and was actually aimed at keeping farmworkers under 18 away from dangerous chemicals and equipment), and the fight over the EPA’s recent thwarted effort to fly over concentrated animal feeding operations to document their impact on nearby waterways. In other words, the nation’s biggest agribusinesses should be able to pollute the landscape and treat their workers precisely as they wish.

Romney also uses the paper to reiterate a shortened version of his energy policy, with a special focus on ethanol, the industry that has raised farm incomes to an all-time high in recent years. The paper reads: “Romney recognizes that biofuels are crucial to America’s energy future and to achieving his goal of energy independence, and he supports maintaining the Renewable Fuel Standard to guarantee producers the market access they have been promised as they continue to move forward.”

What’s also noteworthy is the absence of one important word: drought. This must have been tough for Romney to rationalize while he was introducing the document in Iowa, the same state where the rivers are dry and the threat of frost before rain could keep the aquifers from replenishing. This omission is in line with the candidate’s approach to climate change, one he has worked to reverse ever since a brief period of taking it seriously in 2004. But the irony is especially thick, as the paper hints around the problem: “We already ask our farmers and ranchers to cope with natural disasters. They should not also have to battle a man-made disaster of taxes and regulations from Washington.”

Although Romney’s white paper only briefly mentions the farm bill, the candidate used Tuesday’s event in Iowa as an opportunity to blame Obama for Congress’ failure to pass a bill this summer.

“People have been waiting a long time for a farm bill. The president has to show the leadership to get the House and Senate together,” he told the crowd.

But, as Rep. Collin Peterson (D-Minn), top Democrat on the House Agriculture Committee, told The Hill, this assertion — that Obama has somehow blocked the process from moving forward — is far from the case. He said: “… [I]t shows a complete lack of understanding of what’s going on. The problem is not between the House and the Senate, the problem is Majority Leader [Eric] Cantor [R-Va.] won’t put the farm bill on the floor.”

As veteran agriculture reporter Jerry Hagstrom reported on Obamafoodorama, the Obama campaign responded to this claim by assembling a team of experts. On a press call, former Agriculture Undersecretary for Farm and Foreign Agricultural Services Jim Miller said:

“Gov. Romney is not calling on the Republicans in Congress to pass new legislation, and maybe that’s because his running mate, Congressman [Paul] Ryan [R-Wisc.], and his other Republican allies in the House leadership are opposed to a new farm bill and are balking it.”

“Possibly they’re trying to just dodge the issue altogether, wait until next year in the hope that they can pass a farm bill patterned after the budget proposal that Congressman Ryan managed to push through the House of Representatives that would weaken the safety net,” Miller said.

“It would literally gut our natural resource conservation programs that benefit, not just farmers and the environment, but wildlife and those that believe in outdoor recreation and that want clean air and clean water for their families.”

Now, it’s not uncommon for political candidates to play both sides of the (corn) field like this — especially so close to an election. And it is true that the two biggest federal programs focused on food and farming (food stamps and farm subsidies) won’t be interrupted for lack of a new farm bill, so most of the biggest businesses in the equation (industrial farms and the big food retailers, who rely heavily on food stamp income) won’t be impacted yet.

What about young farmers, organic farmers, and the environment? Well, as the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition’s Ferd Hoefner pointed out recently on Civil Eats, they won’t be spared. “With the expiration of the farm bill,” he writes, “farmers will not be enrolling sensitive land in ecological restoration projects. Training opportunities for the next generation of beginning farmers will dry up. Microloans to the very small businesses that drive economic recovery in rural America will cease. Emerging farmers markets in rural and urban food deserts will not have access to startup grants. Organic farming researchers will not be able to compete for any dedicated research funds.”

In other words, the parts of the equation that are actually about food and farming — and not just big industry? They’re clearly not on Romney’s agenda.