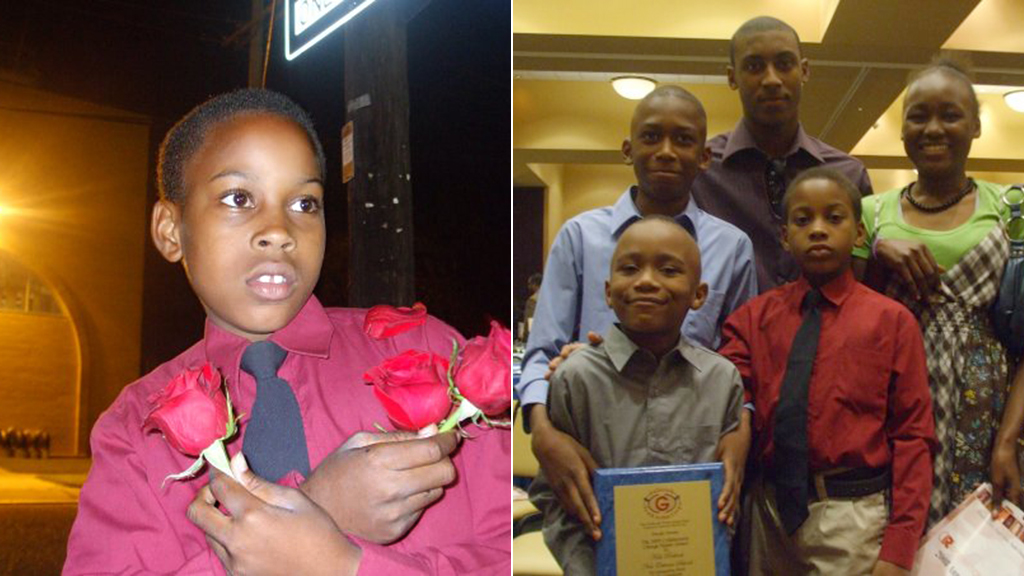

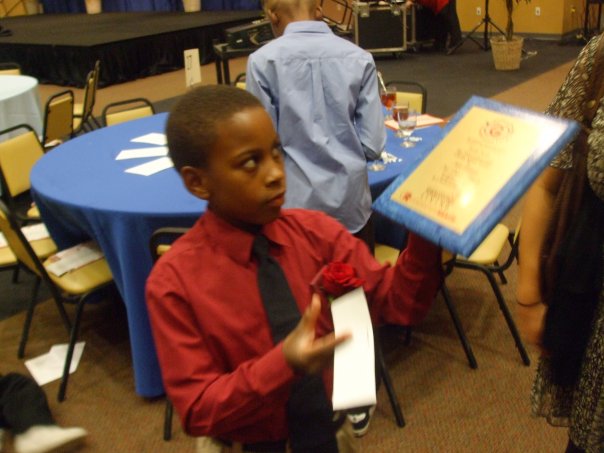

I met George Carter when he was 10 years old, at a banquet where his organization, Kids Rethink New Orleans Schools*, was receiving an award. The “Rethinkers” are young people who came together in 2006, after Hurricane Katrina, to ensure that students’ voices would be heard in the rebuilding of public schools. George joined when he was just 8 years old, following his older sisters and brothers who were leading the Rethink cause. He was the youngest of the group, and hence was dubbed a “Pre-Thinker.”

His thoughts helped mold the organization, which took on school administrations by demanding healthier foods for school lunches and safer learning environments. He loved gardens. He believed they could be a calming presence for young students, especially those recovering from the most traumatic storm disaster the U.S. has known. His thought seeds grew into the kind of ideas and projects that helped earn Rethink an award that night on Oct. 25, 2009.

After the banquet, he posed with his friends holding the plaque and then pranced around the room gathering roses from each table’s centerpiece arrangement. He told me that he was going to be a biologist when he grew up. He decorated himself with the roses and asked me to take pictures of him.

Today, there’s another picture of him I can’t get out of my head, though. It shows George’s body lying on the ground, partially obscured by a cop car. Police around him are scribbling notes.

George was found dead from gunshot wounds yesterday morning. He was 15. His killing was added to an obscene murder count in New Orleans that I find no value in enumerating here. Suffice to say that it is high. Another black life was ended before it could reach its potential.

I’m not writing about George to say he was some exceptional young man. Hundreds of black teenagers and young adults have been killed in New Orleans over the years, and all of their lives matter, whether they were drug dealers or burgeoning biologists. Two women were found dead in New Orleans within 24 hours of George’s death, and I’m as saddened by their killings as I am of George’s. Many people were shot and killed in the four years I lived there, some of whom I knew personally, but all of them equally heart-breaking.

But I want to tell you about George, because his ideas about the transformative energy of gardens needs to live on.

This is George sharing his garden theory, when he was just in fourth grade:

To me I think all schools should have gardens because you can use the plants, and plants give you oxygen. I like to go out in the garden because it calms me down. … If you just had a fight, you can just go in the garden, calm down, eat some strawberries, and you’ll feel safe because you’ll be around nature. And nature, it won’t hurt you.

“This insight was one of the first that connected the idea of school gardens and fresh food to school to the prevention of school violence,” said Jane Wholey, one of Rethink’s founders.

While supplying school students with fresh fruit sounds like common sense, it wasn’t the practice in New Orleans schools (nor in many other schools across America). One of the primary ways that George and the Rethinkers thought they could reform schools was to convince them to provide healthier lunch options. So they did their own study. In 2010, the Rethinkers — aged 10 to 17 — visited various schools across the city, surveying students about their feelings about their school lunches. To little surprise, they found that most kids found their lunch disgusting.

Next step: The Rethinkers stepped to Aramark, the company contracted to provide food for the schools’ lunch programs. George was part of a round of negotiations that led to Aramark agreeing to purchase locally grown fruits, vegetables, meat, and fish for school lunches. No more of the canned, processed stuff. Aramark signed and sealed this contract in 2011, during a press conference organized and coordinated by the Rethinkers themselves. It was hosted at the Hollygrove Farmers Market, and for their guests — a packed room — they served strawberries.

This was all captured in the HBO documentary, The Great Cafeteria Takeover, which is part of its “The Weight of the Nation” series on obesity.

The kids’ logic, as expressed by Rethinker Ashley Triggs in the film: “When people don’t eat, they act out. When they act out, they get in trouble. When they get in trouble, they get suspended, so they need to eat.”

Companies like Aramark had gotten away with providing cheap, processed foods to schools for so long because no one had challenged them on it. Its bottom line did not figure in kids acting out and getting suspended. This macroeconomics lesson was explained by George’s older brother Vernard Carter, another Rethink co-founder, in the doc:

People are putting money before people’s lives and thinking that as long as they have money they’re OK. That makes me wonder what is going on with the world? Why are people leaning towards more of these beliefs? Why aren’t they leaning more towards humane ideals that keeps the human population flourishing and keeps us going?

These were thoughts and values that circulated within the Carter family. They did not arrive at this academically. George’s older brother Victor and sister Victoria were recently the first in their family to go to college. And yet academics have drawn the same conclusions. A study last year from Joan Luby, a researcher from Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, found that:

The effects of poverty on hippocampal development are mediated through caregiving and stressful life events further underscores the importance of high-quality early childhood caregiving, a task that can be achieved through parenting education and support, as well as through preschool programs that provide high-quality supplementary caregiving and safe haven to vulnerable young children.

George didn’t need an empirical study to understand this, though. He was connecting these dots in elementary school. His thoughts on these matters continued to evolve.

In 2012, George sat on a panel for a conference called “Root Of It All: The State of Mental Health of New Orleans’ Youth,” which was sponsored in part by the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice. MSNBC TV news host Melissa Harris-Perry was one of the keynote speakers. When George spoke, he emphasized the stressful environment of schools in his city. Compounding that were the new mandatory standardized tests, which George and his peers found inflexible if not counterproductive to their educational pursuits.

Said George, “If I get stressed I won’t be able to do my work, if I don’t do my work, I’ll probably flunk a class or drop out of school. If I drop out of school I’ll be on the streets. If I’m on the streets I’m gonna be homeless, dead, or in prison.”

He told the conference that New Orleans schools needs support teams in the classrooms that can help with tutoring and serving the students “healthy snacks” throughout the day, because — you know, “when people don’t eat, they act out. …”

“Students and teachers should work together to make the environment healthier,” said George, his voice deeper and more confident than when I first met him at the awards banquet.

As George aged, his interests expanded from biology and gardens to architecture, law, and justice. He started an internship this year through his school with the Capital Post-Conviction Project of Louisiana, which provides legal defense for people who’ve been sentenced to death. His first day was Monday. He was killed before he could make it to his second day. As of this writing, the police have no suspects or motives. According to nola.com he was found on a “narrow street bordered by a fenced-in field on one side and overgrown trees, weeds, and vegetation on the other.”

“I’m afraid to walk down this street,” a woman told the reporter. “The streetlights don’t work, the city don’t cut this. … They could just snatch you and pull you into the bushes.”

The city could honor George’s legacy by converting those bushes into a garden, perhaps with strawberries.

George Carter’s family is accepting contributions to cover funeral expenses. Rethink is processing these donations and 100 percent of funds received will go to the family. Go here to donate.

(*My wife, Thena Robinson Mock, is the former executive director of Kids Rethink New Orleans Schools. One of our first dates was at the awards banquet where I met George.)