This story was originally published by Mother Jones and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Amber Kelley has a “super-cool way” to make fish tacos. “You’re going to start with the natural gas flame,” the teenage one-time Food Network Star Kids winner explained in a professionally produced video to her 6,700 Instagram followers, adding, “because the flames actually come up, you can heat and cook your tortilla.”

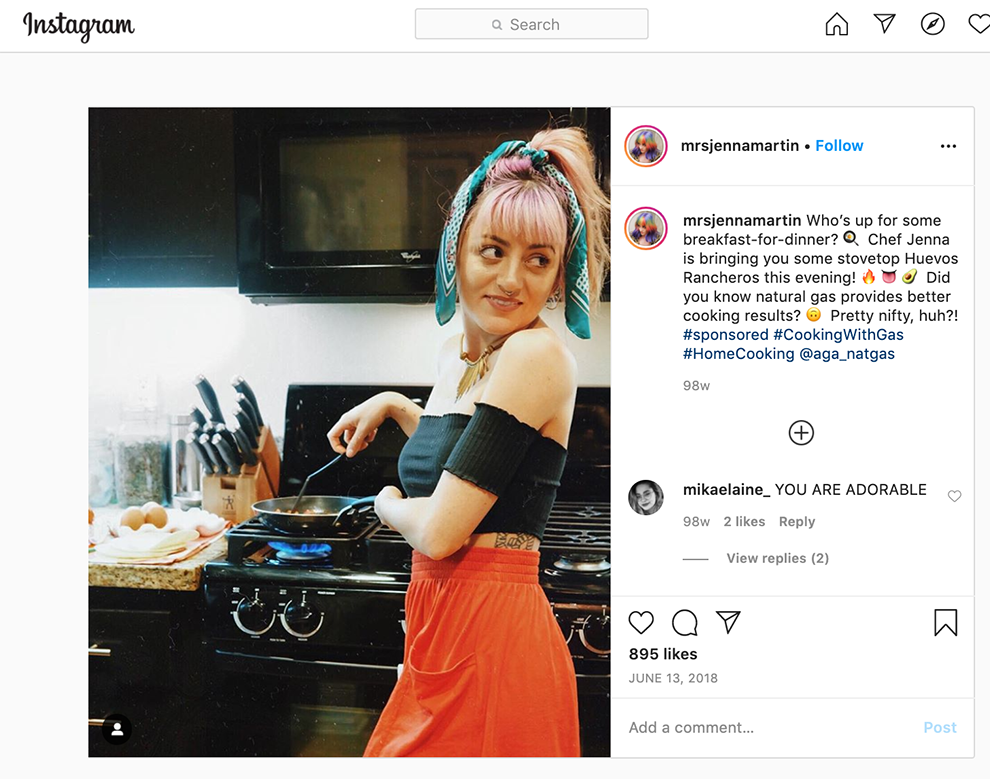

Kelley’s not the only Instagram influencer praising the flames of her stove. “Chef Jenna,” a 20-something with cool-girl rainbow hair and 15,800 followers, posted, “Who’s up for some breakfast-for-dinner? Chef Jenna is bringing you some stovetop Huevos Rancheros this evening! Did you know natural gas provides better cooking results? Pretty nifty, huh?!” The Instagram account @kokoshanne, an “adventurous mama” with 131,000 followers, wrote in a post about easy weeknight dinners that natural gas “helps cook food faster.”

“#cookingwithgas makes food taste better,” says Camille, an L.A.-based foodie who poses artfully with her spatula, to her 16,700 followers.

Mother Jones

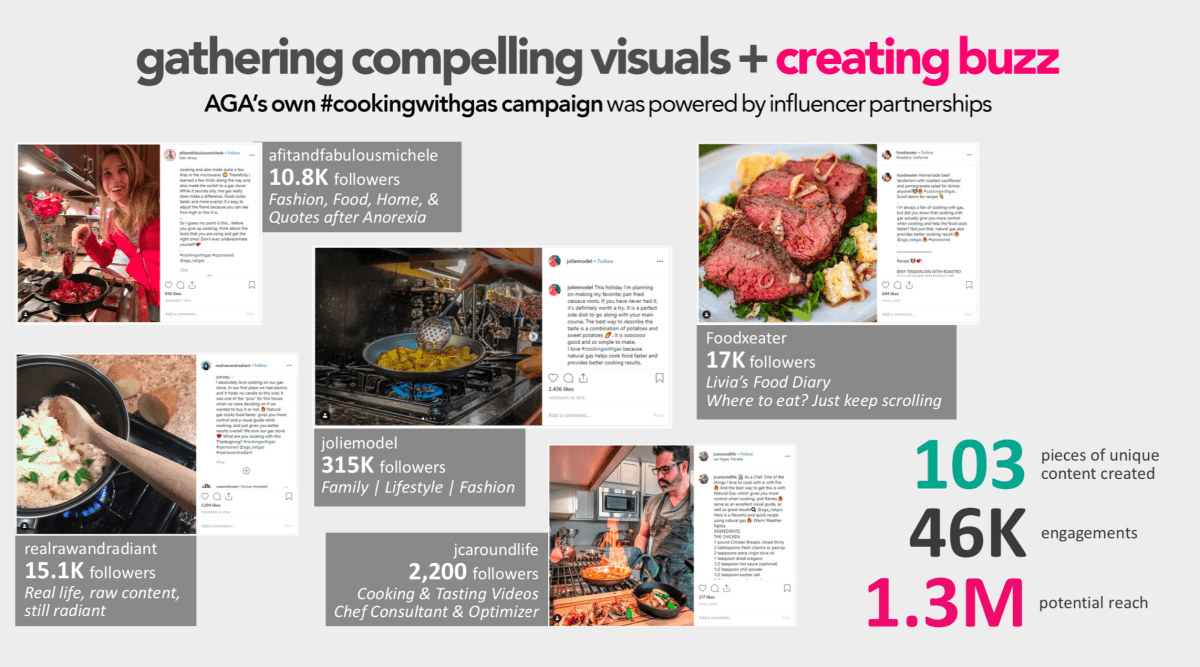

The gas cooking Insta–trend is no accident. It’s the result of a carefully orchestrated campaign dreamed up by marketers for representatives with the American Gas Association and American Public Gas Association, two trade groups that draw their funding from a mix of investor- and publicly owned utilities. Since at least 2018, social media and wellness personalities have been hired to post more than 100 posts extolling the virtues of their stoves in sponsored posts. Documents from the fossil fuel watchdog Climate Investigations Center show that another trade group, the American Public Gas Association, intends to spend another $300,000 on its millennial-centric “Natural Gas Genius” campaign in 2020.

What the polished posts don’t mention is that those perfectly charred tacos and fast weeknight meals come at a steep price: Gas stoves expose tens of millions of people in the United States to levels of pollution so high that they would be considered illegal outdoors. Counting on the allure of Instagram stars to help fend off alternatives backed by environmentalists, the gas industry doesn’t want you to realize how much its paid marketing has influenced public thinking that gas stoves are stylish, innocuous, and necessary home appliances. To the contrary, lifestyle bloggers are building their healthy, clean-living brands on one of the most dangerous home appliances on the market.

Americans have a lot of feelings about their stovetops, and the prevailing opinion is that electric can’t hold a candle to gas ranges. Gas stoves, we’re told, fire up faster, work smoothly with cast iron cookware, and allows better control.

As it turns out, the industry has been working on convincing us of these supposed benefits of gas stoves for a long time — Instagram campaigns are just the latest twist in a 90-year-old advertising campaign. In the 1930s, groups like the American Gas Association needed to stave off competition from wood and electric stoves. An enterprising executive at AGA came up with the slogan to promote the superior experience of its product that has lasted over a century later: “Now you’re cooking with gas.”

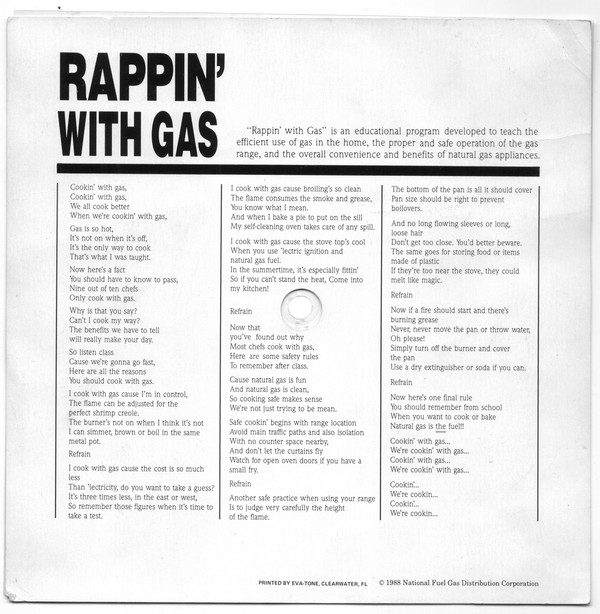

And the industry has long used pop culture to spread its message. In the 1940s, comedian Bob Hope incorporated the slogan into his routines. In 1956, it was actresses playing housewives selling gas-fired appliances in a 13-minute infomercial. In 1988, the phrase took an unfortunate turn in a rap by the National Fuel Gas Distributors, which featured lyrics like:

I cook with gas cause broiling’s so clean

The flame consumes the smoke and grease

You know what I mean.

Mother Jones

Presentations from the PR firms Bellomy and Porter Novelli highlight the thinking behind the ongoing influencer campaign. The intention was never to have ultra-famous influencers on board, the slides show, because these mid-level accounts with a few thousand followers apiece are cheaper and can still reach the desired niche audiences. So with its $300,000 budget from the American Public Gas Association, the PR firm Porter Novelli promises “snackable” content geared towards desirable millennial target audiences, “hispanic millennials,” “design enthusiasts,” “promising families,” and “young city solos.”

Mother Jones

“You can’t help but cringe,” Rocky Mountain Institute’s report author Brady Seals says when she looks at the #cookingwithgas hashtag of gorgeous kitchens and massive gas stoves, because they clearly lack a ventilation system.

Mother Jones

Every time you ignite a gas stove, you’re filling your home with many of the same pollutants in exhaust from cars — carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, particulate matter, and formaldehyde, which are all associated with a range of chronic health problems like respiratory problems and cardiovascular disease.

The problem is worse the smaller the space; cramped apartments fill up more quickly with pollutants. And lower-income African American and Hispanic adults and children face the biggest toll as populations already facing higher rates of asthma exacerbated by more polluted outdoor air.

Two studies out in May added to that research with a closer look at one gas in particular: nitrogen oxide, a building block for smog, that is harmful even in short spurts and at lower levels. And in homes with gas stoves, the concentration of nitrogen dioxide is anywhere between 50 to 400 percent higher than homes with electric stoves. One report, a literature review from the policy think tank Rocky Mountain Institute, Mothers Out Front, Physicians for Social Responsibility, and the Sierra Club, found that children, with their growing lungs and smaller bodies, are especially vulnerable: A gas stove can put them at 42 percent greater risk of developing asthma symptoms, and 24 percent risk of lifelong asthma, in addition to impacting their brains and cardiovascular systems. A second study by UCLA and commissioned by Sierra Club found that if your gas stove and oven were both on for an hour, you’d have enough nitrogen dioxide build up inside your home that it would be considered illegal if you were outdoors.

Indoor air quality has long gotten short shrift because our homes are, of course, private property—there is no agency formally responsible for keeping our indoor environments clean. So while the United States has made progress on outdoor pollution, the indoors—where we spent about 90 percent of our days—can be up to 100 times more polluted than the outside due to emissions from gas stoves and ovens, according to the RMI study. Other gas-powered appliances like water heaters and gas furnaces face more federal regulation requiring ventilation, but stoves have mostly escaped oversight.

The influencer campaigns from the gas industry have ramped up as environmentalists succeeded in convincing 30 cities in California (Seattle and Bellingham in Washington state have considered it) to use electricity instead of gas in new building construction. Though the electrification fights are about bigger battles than cooking, the gas industry saw an opportunity to convince Americans that banning gas would make their food taste less delicious. It’s working: For example, when Berkeley ordered new construction to go all-electric, the California Restaurant Association sued, noting the “uniquely negative impacts” on the culinary community.

As for the health effects of gas cooking, the industry assures consumers that it’s easy to reduce pollution: To minimize the fumes, experts say, you should cook only on the back burners, use the fan, and open windows if you can. Yet the industry marketing campaigns do not mention these safety measures, nor do any of the sponsored Instagram posts.

https://www.instagram.com/p/B5WW42dAlcl/?utm_source=ig_embed

What’s more, most stovetops aren’t outfitted with the kind of range hoods that reach overhead to suck up the fumes to vent outside. Instead, most stoves come with a flimsy fan that does little more than recirculate the dirty air already in your home. While there’s no national data on this, less than 35 percent of California residents use any kind of fan when they cook, and even less have the right kind of hood, according to the UCLA study. (APGA points out that the Consumer Product Safety Commission and Environmental Protection Agency have tested emissions from gas stoves and do not consider them hazardous enough to regulate. “Virtually all gas utilities have existing policies in place evaluating acceptable CO emissions levels from residential gas equipment,” a spokesperson emailed.)

Environmentalists are calling for federal gas stove ventilation standards, but until that happens, there is an alternative that the gas industry doesn’t want consumers to know about: As my colleague Tom Philpott has written, the electric induction range is a glass-top alternative that uses a magnetic field to heat up pans. Though relatively expensive, the method is more precise, faster, and slightly more energy-efficient than gas rivals. Best of all, it doesn’t fill your kitchen with fumes.

Despite the well-documented health risks, gas stoves are still the norm in American households, while just 1 percent have adopted induction—far below what Asian and European countries have adopted. Like the tobacco industry’s misleading marketing campaigns, the gas companies have given the public false faith in these stovetops’ safety in the face of a growing body of research that proves otherwise.

“There’s just a black hole when it comes to indoor air,” Seals says. “It’s a shift to think we have something unvented right in the space that we breathe.”