The ants in my kitchen, unable to resist, have clustered around a drop of sugar water spiked with poisonous levels of boric acid. They drink until they die. Humans are similar, except we don’t need the boric acid; the sugar water itself — in the form of juice, energy drinks, and soda — is the poison. At least it’s poisonous when we suck it down in heroic quantities, until we gain weight, develop type 2 diabetes, and descend into metabolic malfunction.

In theory, humans are different from ants: We can notice when something is making us sick, we can tell each other about it, and we can change our behavior. With sugar, however, we haven’t been able to do that yet, so scientists are looking for the right method. New studies are out assessing the effectiveness of taxes and labels. What will it take to get humans to stop slurping up so much sugar?

Warning labels

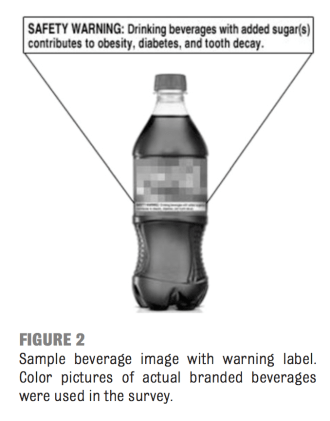

A brand new study suggests that warning labels — like those on cigarettes — might be part of the solution. California and New York are already considering laws that would mandate warning labels on soda and other sugar-sweetened drinks; and the study, published in the journal Pediatrics, found that labels influenced parents’ choices about which drinks they would purchase for their kids. Without labels, 60 percent of parents chose sugary drinks, but when those drinks bore a warning like the one proposed in California, that number dropped to 36 percent of parents.

Roberto CA, Wong D, Musicus A, et al. The Influence of Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Health Warning Labels on Parents’ Choices. Pediatrics. 2016.

This is a pretty big effect, but I doubt that warning labels would work quite so well in real life. Researchers used an online survey to conduct this study, and they enlarged the warning to ensure that everyone saw it. They also cued participants with a note: “drinks with a lot of added sugar have a safety warning label on them.” It’s likely that some of the people taking the survey were primed to click on what looked like “the right answer.” The researchers understood this, they wrote: “This means the study may have overestimated the effect of the warning label, but if we had found no effect, it would suggest that such labels would not be influential in real-world settings.” In other words, the next step is to do real world studies — and there will be ample opportunity for those studies if California or New York calls for a warning label.

Taxes

Lawmakers have already tried boosting taxes on sugary drinks, and there are a couple new studies assessing those efforts. Back in 2012, Mexico slapped a tax on sodas and other sugar-sweetened beverages, and recently the British Medical Journal published a study suggesting that it has made a real difference. The study estimated that the tax had caused Mexicans to purchase 6 percent less sugar water in 2014. That’s not a huge decrease, but the trend seems to be accelerating — people are buying less and less soda as time passes — and the reduction was greatest in the poorer households, which have borne the brunt of injuries from diet-related disease.

There’s also a new study from the American Journal of Public Health, assessing the soda tax that the city of Berkeley passed a year ago. This study didn’t look for a drop in beverage purchases; instead, the researchers asked if retailers were passing the tax on to shoppers. Neither Mexico nor Berkeley tax consumers directly — instead, they tax manufacturers and distributors, who pass on that cost to retailers. In Mexico, the retailers simply bump up the cost of the drinks to cover this cost, but in Berkeley, some shop owners aren’t raising prices.

Overall, retailers in Berkeley were passing on about half of the tax to consumers (and either absorbing the rest, or increasing prices on other items). That’s not great, but it’s a lot better than a previous assessment of Berkeley’s tax had suggested. Furthermore, this paper only covers the first three months of the tax, and the authors talked to retailers who were still unsure how they were going to react — so that pass-through rate may improve.

The nice thing about a tax is that it pays for itself, along with other programs that might be more effective in stopping metabolic disease, even if it doesn’t directly stop people from consuming poisonous amounts of sugar. The sad truth is that we still haven’t figured out a formula for convincing ourselves to eat — and drink — more healthily. In that way, we’re still very much like the ants.