The farming technique known as push-pull — which involves planting grasses with special properties to protect crops — started out as a rudimentary defense against stem borer insects. But it just keeps getting more sophisticated. It has evolved to fight off parasitic weeds, while also providing animal fodder and fertilizing the soil. Now, in a paper published this month, scientists have described ways to use it in areas without regular rainfall or irrigation.

The story of push-pull starts 22 years ago, when entomologist Zeyaur Khan arrived at the International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology station in Mbita, Kenya, with an assignment to find a way to ward off the stem borers that were plaguing corn fields in eastern Africa. When he began studying the stem borers’ lifecycle, he began finding grasses that had evolved with these insects. There were some grasses that the stem borers loved to eat — five times more than they loved the corn. There were other plants that had evolved chemical defenses against the bugs — some by repelling them, and others by attracting wasps that ate them.

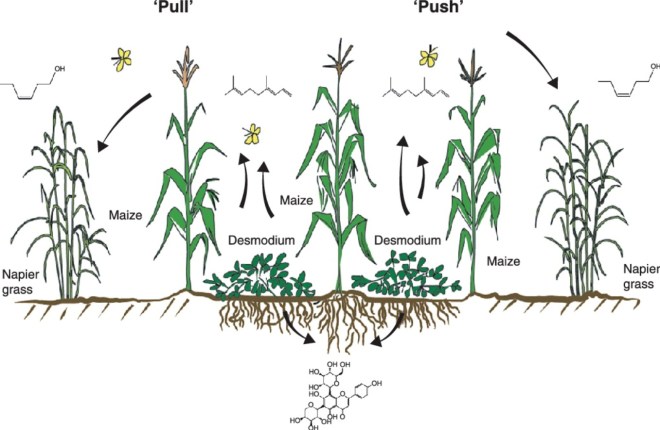

After examining more than 500 different grasses, Khan settled on Napier grass, which attracts stem borers and then, when the insects try to eat it, emits a gummy sap that kills them. By planting Napier grass around a field, farmers could pull the stem borers away from their crop; if they also planted a repellent plant in the field, it would also push the insects away. That’s where the name comes from.

But as Khan was trying to find the right “push” plant, he began to see that, for many farmers, stem borers weren’t the main problem. He remembers one agricultural officer telling him that his innovation was destined for failure.

“He was in tears,” Khan recalled. “He told me, ‘It’s such a nice technology, but it’s not going to work, because striga is going to destroy the crop.’”

Striga-afflicted cornpush-pull.net

Striga, a parasitic plant sometimes called witch weed, looks innocent enough. Drive through Kenyan farmland and you’ll see it: pretty purple flowers blooming among the corn. But it sucks water and nutrients from its host plant, withering and stunting the valuable crop — and siphoning off some $8 billion in production losses from the small-scale farmers who can least afford it. Khan realized that few farmers would adopt his push-pull technique if striga was just going to spoil the crops it saved from the stem borers.

But then Khan walked out into a field where he was testing push-pull plants and noticed something strange: The surrounding fields were heavily infested with striga, but on that particular crop, he said, there were just one or two of the purple flowers. He remembers thinking, Where is the striga? It turned out that the plant they were testing in that field to repel stem borers — the species of desmodium that they had planted between the rows of corn — exuded a selective herbicide into the soil that inhibited the growth of striga roots. It was a happy accident, the result of systematically testing plant by plant.

Farmers liked the combination of desmodium and Napier grass. In addition to protecting crops from striga and stem borers, desmodium fixes nitrogen, which provides a little fertilizer to the crop. Many poor farmers can’t buy insecticide or herbicide or fertilizer — they can’t afford it, or they are too far from roads. Push-pull gives them a renewable source of agricultural chemicals, produced by plants. Farmers started getting higher yields, and they found they could feed the Napier grass and desmodium to cattle.

“Because they’ve become push-pull farmers, they now have the feed, so they’ve got animals. It’s allowed them to diversify,” said Toby Bruce, a plant scientist at Rothamsted Research, who has been collaborating on this project.

By that point the scientists might have simply declared victory and quit, but instead they sought out new problems to solve. While the desmodium and Napier grass worked great in wet regions, these plants would dry up and die in drier areas. Because climate change is bringing more frequent extreme weather events, the scientists set out to find plants that could survive a drought. So, recently, they announced that they’d succeeded with a combination of green leaf desmodium and a brachiaria grass (an African native that was bred for drought resistance in South America). These companion plants will survive anywhere that it is wet enough to grow corn, Bruce said, and regrow year after year without reseeding.

I asked Bruce if this latest iteration was just a small improvement, or if he thought it was a big deal.

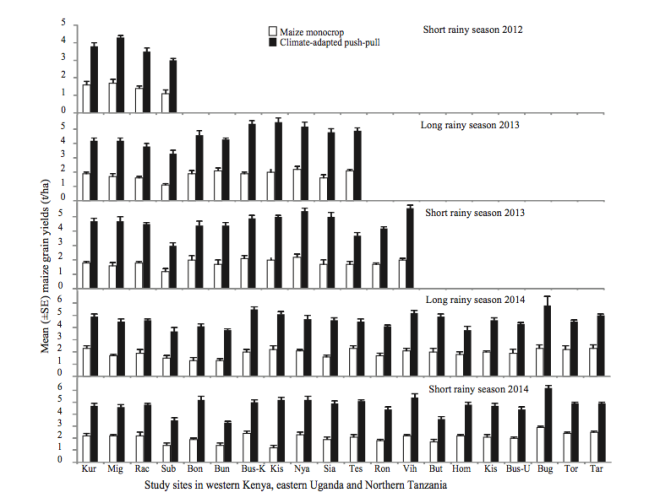

“I think it’s a major deal, actually,” he said. “It does increase the area that this technique can reach, and striga stunts the crops so much. We’ve seen three times more yield [with this new approach] in the badly striga-infested areas.”

Most farm technologies increase yields by a few percentage points. When you start talking about tripling yields over large expanses of land, then you are talking about a major improvement in the prosperity of small farmers and “major significance in terms of feeding people,” he said.

Some 100,000 farmers have adopted the push-pull techniques, the researchers estimate, but there’s a lot more who could use it. There are just so many small farmers in Africa that it’s hard to spread information, Bruce said. And that can be frustrating.

“I was driving out the to the research site in Kenya, and seeing all these fields filled with the purple flowers of the witch weed,” he recalled. Farmers are using push-pull all over the continent, but there are also farmers just miles from the birthplace of the technique who still haven’t heard of it.

There’s a lot of snake-oil on sale to farmers, but push-pull is a technique created and vetted by publicly funded agricultural scientists working at respected institutions.

“It bloody well works!” Bruce exclaimed. “I thought it had been exaggerated when I first started working on it, but if anything it hasn’t been hyped up enough.”

I’m not sure if any small African farmers read Grist, but I’m happy to help with that hype. And perhaps this presents an opportunity for wealthier farmers who are ready for an alternative to business as usual — whether they are driven to alternatives by regulations, declining effectiveness of pesticides, or a simple desire to grow food in a more sustainable manner.