Vermont – mention the state, and people picture the soft-focus Holsteins on Ben & Jerry’s ice cream cartons and postcard pictures of cows grazing in a hilly, pastoral heaven. And for good reason: As New England’s leading milk producer, the Green Mountain State has a huge cultural and financial investment in dairies.

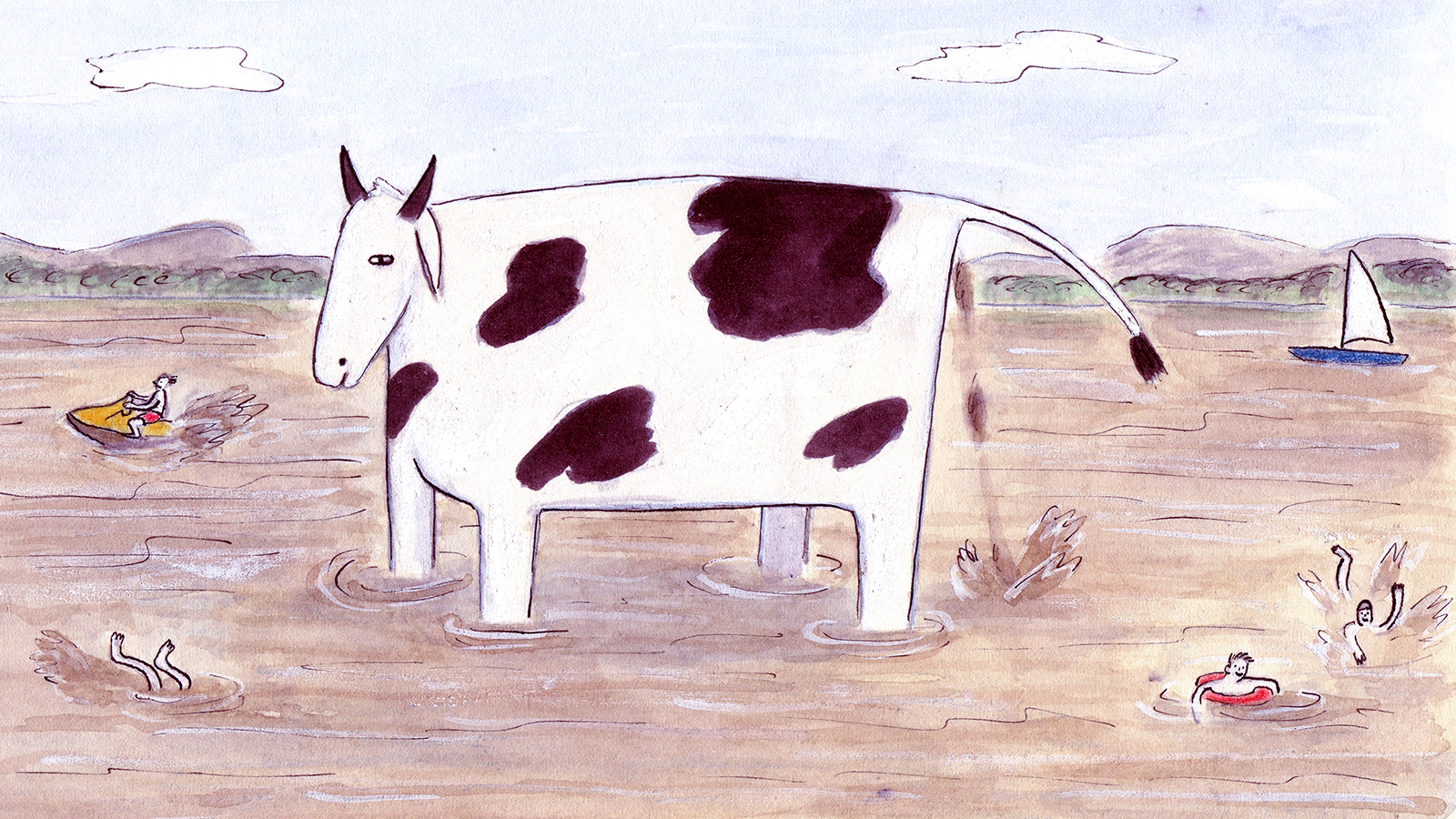

Amidst all the bovine iconography, however, here’s one image you’ll never see: Bessie pooping in the sparkling waters of Lake Champlain. But increasingly, waste from Vermont’s lightly regulated dairy farms is polluting the lake, the nation’s sixth-largest body of fresh water. It’s undermining Vermont’s tourist economy and jeopardizing drinking water supplies for a third of the state’s population.

The damage is obvious in the murky gray-brown stains spreading at river mouths, the slimy masses of weeds choking bays, the rotten stench wafting over the sluggish water in late summer when the blue-green algae blooms.

State officials say the biggest culprit is farm runoff, responsible for 40 percent of the phosphorus pollution in the lake as a whole and up to 70 percent in the worst-polluted sections. The phosphorus feeds out-of-control aquatic weeds and algae; at its worst, the rampant growth can strip the water of oxygen, suffocating all other life and generating toxic cyanobacteria.

As a result, some Vermonters now say that while the dairy industry is sacrosanct in Vermont, it’s time to corral this sacred cow.

“Here we are, the Green Mountain State, with this enormous environmental reputation that’s only partially deserved,” said Jon Erickson, interim Dean of the Rubenstein School of Environment and Natural Resources at the University of Vermont. “We haven’t really regulated our own water, one of the most critical resources we have.”

* * *

That Vermont would be in such a plight may come as a surprise, given its progressive reputation, from being the first of the United States to launch single-payer health care to its battle to defend the nation’s first GMO-labeling law.

But Erickson, who produced an award-winning 2010 documentary about Lake Champlain’s woes, says Vermont is on the cutting edge this time, too: It may well become the first state to forfeit its environmental authority to the federal government.

In 2002, the federal Environmental Protection Agency granted Vermont power to enforce the Clean Water Act within state borders in an agreement that included a pollution-management plan for Lake Champlain. That plan established a “Total Maximum Daily Load” for phosphorus. As the name suggests, a TMDL establishes legal limits on how much of a given pollutant a body of water can safely absorb. But in 2008, the public-interest Conservation Law Foundation sued the EPA, saying the TMDL was far too lenient. In response, in 2010, the EPA invalidated Vermont’s plan, essentially putting the state on probation while it comes up with new pollution-control proposals.

For now, as federal authorities evaluate whether they need to take over, the state retains its Clean Water Act powers. But Vermont has had a tough time proving it’s serious about a cleanup. In early May, the EPA rejected the state’s proposed strategies to meet minimum Clean Water Act standards.

Gov. Peter Shumlin tried again, promising in a May 29 letter to the EPA that his administration will make farms cleaner — especially small dairies, which until now have been largely unregulated. Still, Vermont has yet to even bar cows from creeks and rivers, or the lake itself.

Roger Rainville of the Farmers Watershed Alliance – a leading agricultural spokesman on environmental issues — resists such a ban. “There’s a lot of wildlife in this state, and there’s a lot of things that crap in that water, not just cows,” Rainville said. “The public perception is, ‘I see that cow there. She’s causing problems.’ Well, we have to put our money where it has the biggest impact, and livestock in the water is not the biggest impact.”

The revised lake cleanup plan accompanying Shumlin’s letter offers “strengthening of the

livestock exclusion requirements” by early 2016. That word “requirements” is slippery: The plan describes incentive programs, such as helping farmers pay for fencing, but it never mentions any universal ban on cattle in the water. It makes little mention of enforcement on other issues, either, beyond pointing out that there’s little money to pay for it. Small farms wouldn’t have to meet whatever stricter pollution-control rules that may be developed until 2020.

* * *

If Vermonters can’t even impose a no-crapping-in-the-water rule, how will they ever get to the rigorous response the crisis requires?

Chuck Ross, the state’s agriculture secretary, and David Mears, who heads the state Department of Environmental Conservation, said new farm rules aimed at reducing runoff could be modeled in part on proposals by the Conservation Law Foundation. One such recommendation calls for planting a cover crop, like rye, that would remain in the fields after the corn harvest, helping to hold the soil together and reducing erosion. Another would bar farmers from planting crops too close to riverbanks, leaving natural buffers of grass or brush to catch runoff.

James Maroney has another solution. A New York refugee, Maroney owned Vermont’s largest organic dairy from 1986 to 1995, when a fire leveled his barn. He believes that organic farming is the salvation for Vermont’s waterways and its farmers both. He preaches his message through innumerable appearances before the state legislature, letters, op-eds, YouTube videos, and a self-published book.

Maroney says only organic, pasture-based farming – which commands higher milk prices — offers an economically viable alternative to the dominant Concentrated Animal Feeding Operation (CAFO) model, which involves ever larger herds, kept in barns and fed on phosphorus-fertilized corn and grain planted on the state’s most highly erodible floodplains or imported from the Midwest.

James Ehlers, executive director of the environmental nonprofit Lake Champlain International, advocates buying out fields that are pollutant sources and turning them to other uses, possibly agriculture that doesn’t require as much fertilizer, or leave the soil as open to erosion, as corn. He admits it’s “not an easy political sell.”

Ehlers says there’s already technology to take advantage of the nutrients that are growing toxic algae in Lake Champlain. He cites one company that has developed a “floating island” system, using microfiber mats that can support water-borne meadows. Ehlers wants to find out whether they could be used to grow cattle feed while soaking up phosphorous from the grievously polluted Missisquoi Bay.

Such plans have no part in Vermont officials’ proposed solutions to the lake’s contamination, however. And as the EPA considers whether to accept the state’s newest proposals, environmentalists and farmers, both, are getting fed up with the bureaucratic back-and-forth.

Christopher Kilian, the Conservation Law Foundation’s Vermont director, says his group’s proposals for cover crops and stream buffers are only a start, and should have been required 20 years ago. He believes it’s time to impose harsher penalties on polluters.

“The main way we’ve regulated the dairy industry in this state has been the carrot approach, to give payments for planting trees or changing practices,” Kilian said. “We need a stick.”

Rainville, the environmentalist farmer, says some clear direction would be a better place tostart. For decades, he says, government advisors pushed nitrogen as the dairies’ best friend. Now, he and his neighbors are trying to comply with new directives like restrictions on spreading manure on fields in the winter when the frozen soil can’t absorb the waste. They’ve already tried CLF’s cover cropping suggestions, with mixed results. Vermont’s growing season is so short, it’s hard for the secondary plantings to take hold, Rainville said.

“We as farmers are saying, ‘What the hell do you want us to? We’re listening to what you’re telling us. You get it right and we’ll get it right,’” he said.

Federal regulators are reviewing the governor’s newest proposal. There’s no hard deadline for them to accept or reject it. Meanwhile, the lake’s nutrient counts just keep going up.