In the summer of 1997, fish in the Chesapeake Bay started turning up dazed, dying, and covered with bleeding lesions. The culprit was a toxic microbe called Pfiesteria piscicida, which was flourishing in the warm, polluted waterways. The one-celled organism, discovered less than a decade earlier, had already killed millions of fish in North Carolina. Now it had spread north — and it was infecting humans, too. More than a dozen watermen exposed to the microbe-laden water fell ill with sores, intestinal woes, and neurocognitive impairments such as confusion and memory loss.

By September, with a national media panic in full gallop, three Maryland rivers were closed to all commercial and recreational use. Seafood sales plummeted, as buyers swore off Maryland crabs and other bay delicacies. An investigative commission blamed the outbreak on high levels of phosphorus, a byproduct of the region’s vast chicken industry.

Take that kernel of reality, add steroids, CGI, and the herky-jerk verisimilitude of the found-footage horror genre, and you have The Bay, director Barry Levinson’s spookily plausible exercise in old-school cautionary eco-freakout. The film hits theaters this Friday, Nov. 2. Here’s the trailer:

For viewers familiar with the 70-year-old director’s work — whether his autobiographical “Baltimore Trilogy” of Diner, Tin Men, and Avalon, or commercial entertainments like Rain Man and Good Morning, Vietnam — The Bay is a striking departure, a low-budget gross-out in the vein of recent horror hits like the Paranormal Activity franchise (whose creators, Jason Blum, Steven Schneider, and Oren Peli, serve as co-producers here).

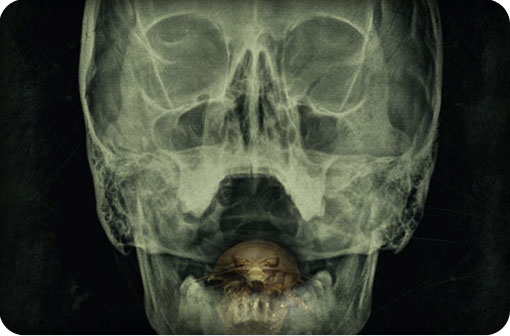

The premise: A young TV newscaster witnesses a mysterious environmental catastrophe over the Fourth of July weekend in a small town on the Chesapeake Bay, an incident that is only exposed three years later via a WikiLeaks-esque data dump of footage. Instead of toxic microbes, the monsters of The Bay are parasitic isopods — evil-looking sea lice that look like overgrown pillbugs. Juiced by the chemical-laden chicken manure that’s been dumped into the waterway, the isopods start breeding like crazy and infesting human hosts instead of fish. Bloodbath ensues.

That last bit isn’t super likely to happen, but Levinson insists genially that The Bay is “85 percent real,” in part because the project began as a straight documentary about the environmental challenges facing the Chesapeake Bay. He switched tack after watching Frontline’s 2009 report “Poisoned Waters” and concluding that he wasn’t likely to top it.

The PBS doc cataloged the real-life horrors that bedevil the bay three decades after the passage of the Clean Water Act: frequent fish kills, lethal algae blooms, oxygen-depleted dead zones, and the near-elimination of life-sustaining underwater grasses and wild oysters, which once acted as a natural filtration system.

“Forty percent of the largest estuary in the nation is dead,” Levinson says. “But where’s the outrage? I’m a storyteller, not an activist. So I thought, what if I took all that information and put it into a fictional device?”

The Bay is a clever composite of the real and imaginary. Levinson liberates his movie from the physical limitations of the found-footage conceit — call it the Cloverfield conundrum — by assembling a documentary-like collage from multiple perspectives: TV news footage, cell phone videos, closed-circuit television, cop car dash cams, and Skype conversations between exposition-spouting CDC scientists and a plucky ER doc who tries in vain to figure out what’s eating his patients.

The film, Levinson says, layers 21 different kinds of cameras and forms of media: “I looked on it kind of like an archeological dig.”

The plot borrows beats from zombie movies, Cold War atomic scare pictures, and ’70s-style eco-fables, but the strongest echo might be the first hour or so of Jaws: There’s even a doofus mayor who labors to keep a lid on things even after the tourists start dying.

And, yes, The Bay is scary, inasmuch as a movie about tainted seafood could be. It’s no mean feat wringing chills from the placid, bathtub-warm Chesapeake, which must be the least-frightening famous body of water this side of Walden Pond. Levinson compensates by focusing on icky, small-scale body horror, as victims use their cell phones to document the nasties gnawing through their innards. In one memorable scene, a fist-sized isopod leaps from the mouth of a striped bass and tries to nosh on a fisherman.

A leap of the imagination? Perhaps, but for those who recall the pfiesteria scare, it’s haunting to see infected striped bass again. During the summer of 1997, scenes of striped bass (known locally as rockfish) covered with bloody sores were go-to b-roll on the evening news, shorthand for an ecosystem gone horribly awry.

And the notion that new bugs could jump from animals to humans is all too real. It’s called zoonosis, and it’s the kind of stuff that keeps infectious disease experts (and readers of David Quammen’s new book Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic) awake at night with fears of superviruses breeding in distant rain forests. The evil genius of The Bay is that it projects this abstract unease into what is essentially America’s backyard swimming pool, turning a beloved watery playground into a literal reservoir of disease.

Typically, Levinson’s films get a hero’s welcome in his home state, but this one might be an exception. The Bay was actually shot in coastal South Carolina, which makes a convincing stand-in for the Chesapeake, and no doubt allowed the filmmaker to avoid some awkward conversations with Maryland’s tourism authorities.

He still hasn’t heard anything from the Maryland Film Office or other state boosters. “I have a real love for Maryland on a lot of different levels,” Levinson says. “But what are you supposed to do? Stay quiet? Do nothing? The thing is, all of these problems [with the bay] are correctable. We’ve just been kicking them down the road.”