At the beginning of Ann-Helén Laestadius’ novel Stolen, 9-year old Elsa skis to her family’s reindeer corral in northern Sweden as the low winter sun sets. Elsa, who is Sámi and comes from a family of reindeer herders, relishes the freedom of skiing alone, and caring for the animals. Hoping to surprise her family by preparing feed bags early, she instead finds her favorite reindeer killed and mutilated and the killer still at the scene. In only a few pages, Laestadius brings readers into Elsa’s wonder-filled world where she is surrounded by family and nature, and shatters it as the killer drops a severed reindeer ear in the snow before zooming off on his snowmobile.

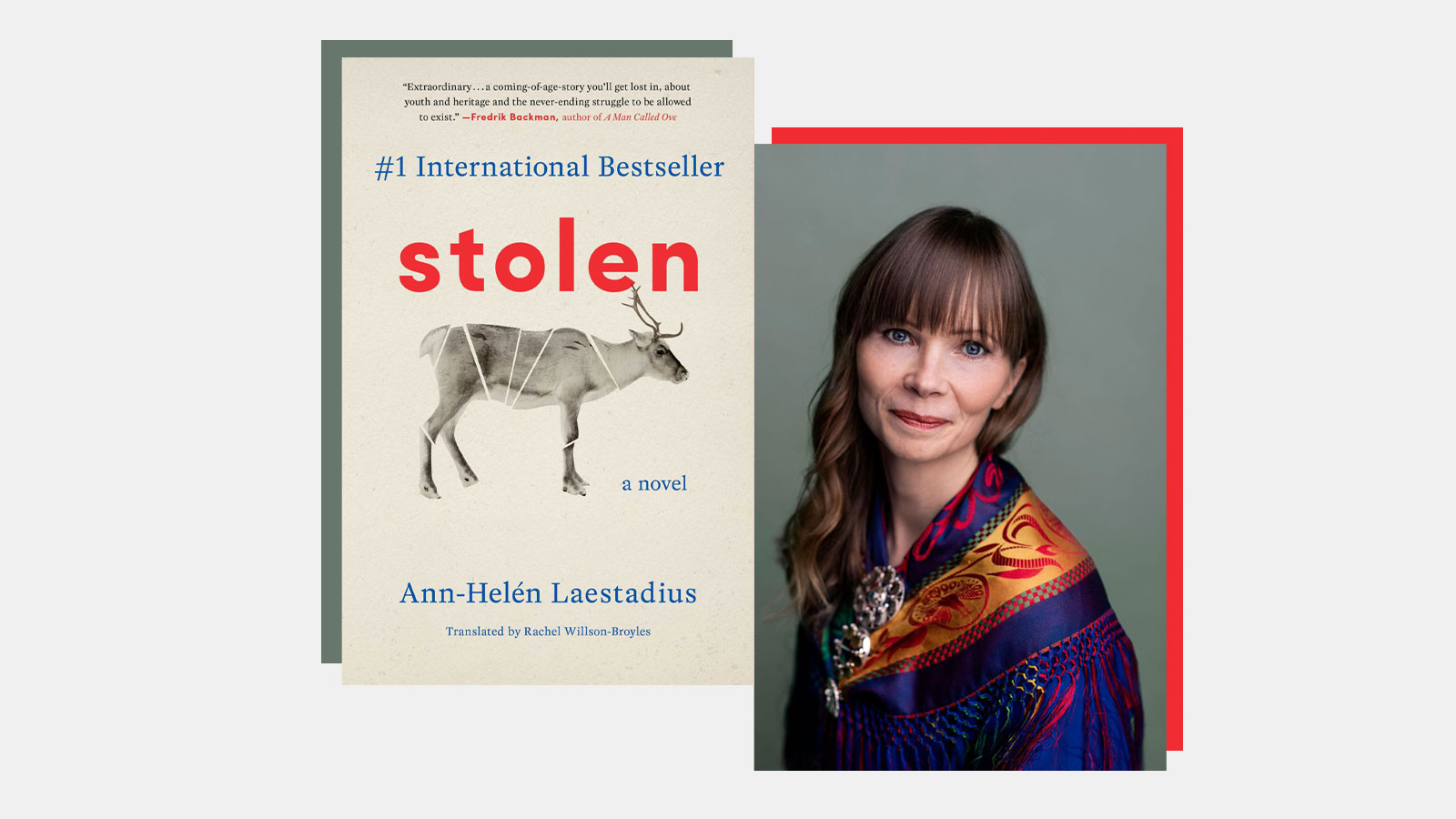

Now translated into English by Rachel Willson-Broyles, Stolen was a #1 paperback bestseller and won two national prizes in Sweden, where it was published in 2021 and is being turned into a Netflix film. From its early moments to Elsa’s decisive encounter with the man who killed her reindeer, Stolen grapples with trauma and racism directed at Sámi people. Bigotry infects nearly every part of Elsa’s life, from her job at a local school to her father’s Facebook page. At almost every conceivable level, the Sámi are let down by journalists, mental health providers, and law enforcement. But Laestadius has gone beyond crafting a thriller built around a coming of age story. She has neatly side-stepped clichés about Indigenous communities to reveal a loving portrait of a community fighting to survive, and the complexity of a multigenerational struggle seen through the eyes of a young Sámi woman.

Laestadius, who is Sámi and of Tornedalian descent, has crafted a cautionary tale on the power of listening. From the very beginning, we know exactly what the problem is, and who the main villains are, but Elsa spends almost the entirety of the book trying to get people to listen to her community about their reindeer, about climate change, and about racism. The title alone alludes to this, as Swedish police insist that the reindeer killings are simply theft and don’t merit serious investigation.

In Stolen‘s central conflict over reindeer, local officials rile up anti-Sámi sentiment, police are openly dismissive of Sámi concerns, and prejudicial laws limit the Sámi’s ability to seek justice for violence directed at them and their animals. Some of the gory details of bloody reindeer parts strewn across the snow may seem fantastical, but Laestadius has based Elsa’s story on real-life events: in 2020, after Sámi reindeer herders won a key court case that recognized their exclusive hunting and fishing rights on their land, they faced waves of racism, death threats, and the killing and dismembering of their animals.

In this community, frustration is an inheritance. Some succumb, losing hope in the face of generations of neglect. Others, like Elsa, turn it into fuel. From Elsa’s grandparents who experienced state-mandated boarding schools where Sámi were forced to become Christian to the bullying her younger cousin faces at school, Laestadius shows us that in most ways, nothing has changed while the systems set up to provide support, fail. At one point, Elsa overhears her mother tell her grandmother, “If I have to take her to a counselor every time we find a dead reindeer, I’ll have to get a punch card.” A kind of gallows-humor to be sure, but in both Stolen, and the real world, most mental health providers don’t speak the Sámi language making therapy difficult, while providers are non-existent in Elsa’s rural, Sámi community.

As Elsa ages, Stolen explores how a young woman balances her Sámi identity. She has an apartment in town, but misses her home. She works part-time at the local school. One friend enthuses over getting married and decorating her new home. Another plans to become a lawyer. All the while Elsa devotes herself to defending reindeer, writing letters to the police, filing reports, and pursuing the man she encountered as a child.

In a move that upsets some Sámi leaders, Elsa turns to the media, learning to use the colonial gaze to her advantage. In the aftermath of a particularly gruesome reindeer attack which garners widespread media attention, Elsa and a friend joke about how journalists characterize Sámi land as “lawless” and “wilderness.” When a reporter from the Sámi division of Sweden’s national radio station arrives to cover the story, Elsa is able to have a more nuanced conversation. But the audience that needs to be reached by that reporter is unlikely to listen to the Indigenous broadcast, leaving national audiences exposed only to non-Indigenous reporters’ stereotypes.

When outsiders and tourists float through to buy Sámi goods and crafts at the annual winter market, they gawk at Elsa’s traditional Sámi gákti and take photos — moments of racism Indigenous readers will find all too familiar. Elsa is also faced with the most impossible of tasks throughout the book: stick to her traditions and be labeled as backwards and resistant to the modern world, or accept technology and “modern” conveniences making her instantly less Indigenous. Laestadius’ intricate depictions of moments in Indigenous life like these shine, but she is careful not to idealize Elsa or shame other characters. Simply being Indigenous is its own form of resistance.

Stolen‘s kaleidoscopic view of racism and trauma is effective, but sometimes unbalanced. Robert, the killer from the opening pages who terrorizes Elsa throughout the book, is often drunk, lives in an unkempt home, and has a difficult relationship with his family. He is a compelling villain when seen through a traumatized 9-year-old Elsa’s eyes, but as she grows up, he becomes an oversimplification of the pervasive nature of anti-Sámi racism. If the institutional racism faced by the Sámi reveals anything, it’s that social outcasts aren’t actually acting alone, and that a wider network of accomplices — united and organized through condescension, hatred or silence — enable their actions.

A series of minor characters shows just how widespread this is. There’s Astrid, the school lunch lady who has been reprimanded for repeatedly using a racial slur. Years later, in the aftermath of another reindeer attack, Astrid is interviewed by a television news reporter and asked to provide her point of view on the incident, despite having almost no connection to the issue beyond having loud and racist opinions about Sámi people. Then there’s the restaurants and companies that buy illicit reindeer meat from Robert, a black market that pulls at the notion that Stolen‘s villain is simply a rogue operator. It also shows just how profitable racism can be.

What Stolen may do best is make clear how hollow words ring when world leaders talk about protecting Indigenous land and people — a notion that echoes well beyond the pages of Elsa’s fictional story. If officials are not willing to provide basic human rights protections, how can they be expected to commit to global efforts to fight climate change? “They had raised the alarm, trying to get people outside the reindeer grazing grounds to understand — can’t you see what’s happening? We’ve known for a long time!” Elsa fumes as climate change intensifies its effects on her community.

Outside of Stolen‘s fictional pages, Elsa’s battle echoes in university research labs and United Nations meeting rooms. The Sámi’s traditional lands are located mostly in the Arctic Circle where global warming is happening four times faster than the rest of the world. In Sweden, extractive industries continue to threaten Sámi pastoralists, and in Norway, green energy wreaks havoc on traditional reindeer herding grounds. Perhaps Stolen‘s most reflective element is a clear understanding of how generations of Sámi have lived in harmony with their world, and how violence has worked at every level to unravel that knowledge and relationship.

“Being Sámi meant carrying your history with you, to stand before that heavy burden as a child and choose to bear it or not. But how could you choose not to bear your family’s history and carry on your inheritance?” Elsa asks herself.

Laestadius makes it clear that Elsa and the real life Sámi activists will keep fighting, but that true responsibility rests with the rest of the world. In this way, Stolen is both a lesson and a warning.