This article is part of Ask Umbra’s guide on How to Dress for the Planet.

A few days after the outdoor apparel brand Arc’teryx opened a new location in New York City last November, a man stopped by in need of a jacket repair. He was from Massachusetts, and had been ski touring in the Berkshires with the same Arc’teryx coat for more than 10 years. “It was just completely shredded,” said Adam Grossman, the store manager. “I told him I’d do what I could.”

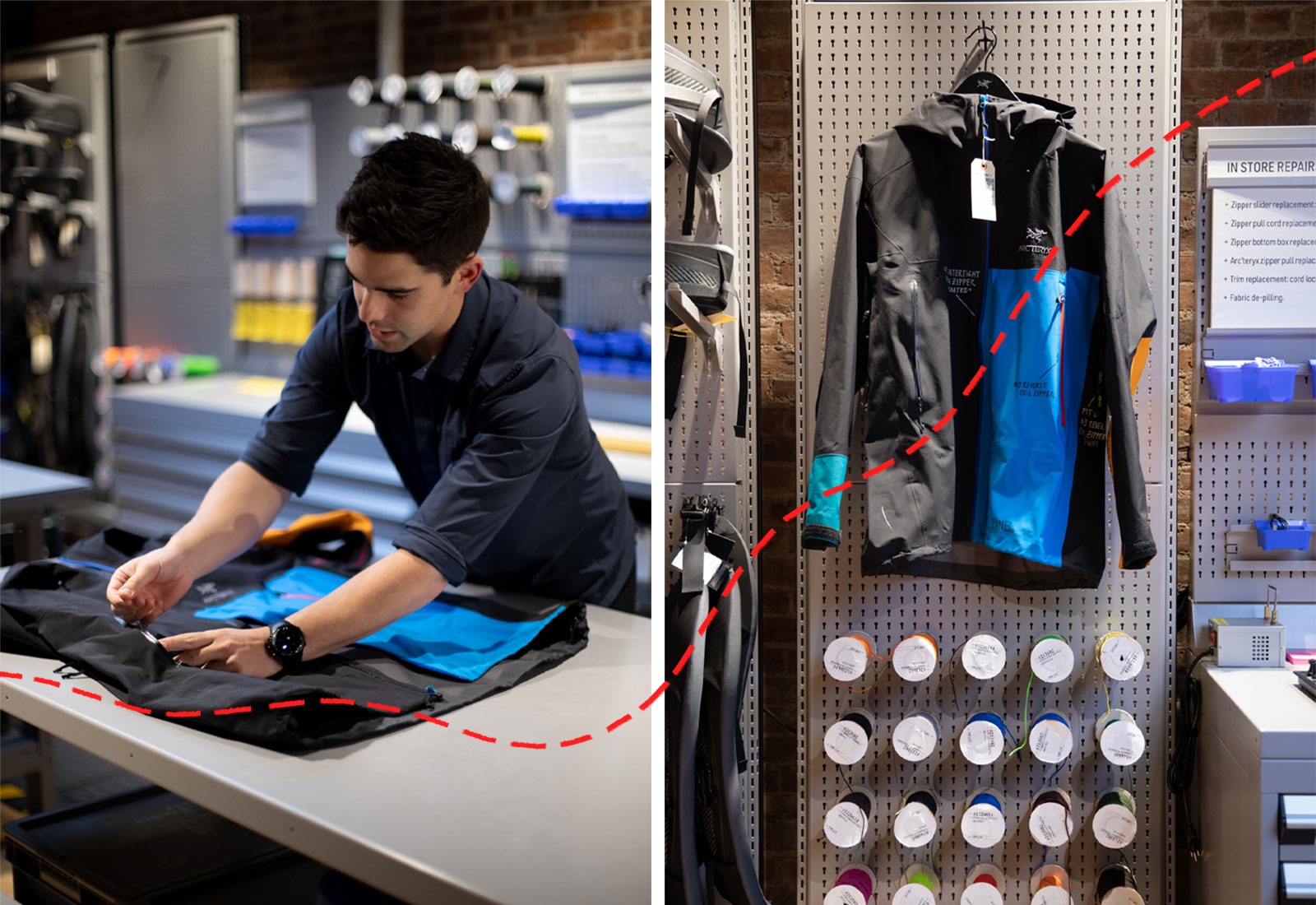

The store housed Arc’teryx’s first in-store repair center, outfitted with two large work tables and drawers full of zippers, patches, and cords. There was a heat press for applying GORE-TEX patches to jackets, a depiller to remove fuzz from sweatshirts, and a machine that shot out water to test waterproof jackets.

Across from the repair space stood another first: a used gear section, where dozens of pre-owned, cleaned, and sometimes refurbished pieces of Arc’teryx apparel hung neatly on racks. An Arc’teryx jacket can run you $1,000, but these items were about 30 percent* less than their original price. Grossman showed the customer a used coat with a much more durable fabric than the one he had, and the man bought it. The man was delighted, he told Grossman. For environmental reasons, he only bought secondhand.

The customer’s reluctance to buy a brand-new jacket makes sense. Beyond the sheer cost of replacing items, the fashion industry’s environmental footprint is staggering. CO2 emissions from textile production topped 2.1 billion tons in 2018, more than the emissions of France, Germany, and the UK combined. A McKinsey analysis found that the fashion industry would need to cut emissions in half by 2030 to align with the Paris Agreement goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. Textile production – including cotton farming – uses about 93 billion cubic meters of water a year, and utilizes harmful pesticides and chemicals.

The industry’s outsized impact has grown in tandem with the rise of fast fashion. Retailers like H&M, Zara, and Shein release new items at lightning speed and sell them at prices that are cheap enough that people can constantly refresh their wardrobes. McKinsey found that annual clothing production exceeded 100 billion garments in 2014, more than double what it was at the start of the millennium. Consumers are also keeping their clothes for half as long, according to the report, discarding some pieces after seven or eight wears.

Enter resale, or the curated selling of used clothes, which has the power to put a sizable dent in apparel’s environmental impact. “Even with the shipping, the transportation, the cleaning, the storage, a resale item carries a carbon footprint that’s about five to 15 percent the size of making a new thing,” said Nellie Cohen, who built and directed Patagonia’s recommerce program until 2018.

Resale has exploded in the last decade, thanks to startups like Poshmark, Depop, and ThredUP, which are fashion-focused online marketplaces for secondhand clothes. The resale market is expected to triple in size from 2021 to 2025, to $47 billion.

Until recently, only veteran climate do-gooders like Eileen Fisher and Patagonia were selling used clothes themselves. But in the last two years, resale has broken into the mainstream: Levi’s, Madewell, and lululemon all have online secondhand shops.. Timberland will start selling used, refurbished boots online this spring. Now that customers can buy clean, vetted, and curated secondhand items directly from their favorite brands, there is a chance that buying used clothes could become as natural as buying new. But whether resale benefits the planet will depend on if it actually offsets consumption, or promotes it.

Eileen Fisher was the first major retailer to start a resale program in 2009. It began as a grassroots effort to collect employees’ used garments, resell them to customers, and donate the proceeds to Eileen Fisher’s charity foundation.

Resale fit naturally into the company’s well-known design ethos, which is built around a wardrobe of timeless, monochrome pieces that can easily be mixed and matched and last for many years. “Our whole business is targeted to durable, simple dressing,” said Carmen Gama, director of circular design. “We’ve had returns of garments that are 30 years old and they’re still completely wearable.”

The “Renew” program was so popular that the company quickly expanded it. There are two Renew stores in New York and Seattle, and the company sells used clothes at some of its main locations as well. They launched a Renew online store in 2017. The program even includes a line called “Not Quite Perfect,” which contains pieces with slight blemishes, like pilling or a small pull, which are sold at a larger discount.

Most resale programs work similarly to Renew: If you have a garment you no longer want that’s still in good condition, you can turn it in for store credit, and the brand will turn it around and sell it to someone else at a discounted price. Eileen Fisher estimates that Renew has taken in more than 1.5 million garments since it started, and by replacing new purchases, saved more than 499,000 pounds of CO2.

By selling their own secondhand clothes, brands are confronting retail’s biggest environmental challenge: how to keep making money without extracting new resources. But what’s likely propelling the trend now is that it just makes good business sense.

Andy Ruben is the CEO of Trove, a backend service that operates Eileen Fisher’s resale program, along with those of Patagonia, Arc’teryx, and others. Trove processes trade-in items at their facility in Brisbane, California. It’s their software and algorithms categorizing and pricing the items, and their platform powering the online secondhand stores. Services like Trove are accelerating the growth of resale because without them, the logistics would be too heavy a lift for most companies. In 2020, Trove processed 1 million secondhand items.

Ruben figures that for every piece of clothing that a premium brand has for sale in one of its stores, it probably has 10 times as many viable pieces sitting unworn in someone’s closet. Some of those items will be “donated,” which often actually means winding up in a landfill, and some will be sold on a third-party site. But if a brand can get those items back into their own retail stream, they can sell them a second time, or perhaps many times over.

“That is the future,” Ruben said. “Because Patagonia would love to sell a jacket five times, not once. Right? Who wouldn’t?”

For customers, resale lets them afford aspirational brands, shop conscientiously, and – just like traditional thrifting – find unique items. When I visited the Arc’teryx store in New York City, a glistening blue men’s coat sat on the front rack. It was a discontinued Firebee AR parka, with a GORE-TEX shell and down insulation. “This is one of our most iconic pieces of the last 10 years,” Grossman said. The zipper had been replaced with one that was a lighter shade of blue than the original, making the coat one of a kind. Many of the jackets had mismatched patches and zippers. “These are flying off the shelves first,” Grossman said.

Ruben believes that resale’s most powerful environmental lever lies in “diverting dollars from brands with less environmental ethos.” If people are able to afford a used, durable, premium item from a brand with a responsible environmental ethos, they won’t buy new, low-quality items that were harmfully produced and won’t last.

If some companies can’t cash in on the resale trend because their products don’t last long enough for a second life, they might start making more durable, repairable goods. “I think it’s going to enable brands to create higher quality items because they’re not just going to look at selling that item once,” said Amelia Eleiter, CEO of Debrand, a textile recycling logistics company. “They’re going to invest in building something in a way that can be refurbished.”

Environmental initiatives that make a company money, rather than costing them money, will ultimately have more staying power. “Resale is the only sustainability program where you can go into the C-suite and be like, ‘We’re going to make money,’” said Cohen, who now runs her own sustainability consulting firm. “We need more sustainability programs like that, because then when there’s an economic downturn or a brand has a bad year, the program doesn’t get cut.”

Like every sustainability program, however, whether a resale program actually helps the environment or is simply greenwashing depends on the details.

The reality is that much of what customers try to trade in simply isn’t in good enough shape to resell. This presents a great opportunity to repair or recycle clothes, but only if companies make the investment. “This whole takeback thing that’s going on, you’ve got to be really thoughtful in how you do it,” said Eleiter.

Her company Debrand sorts Arc’teryx’s end-of-life products through 17 different channels, a combination of recycling, targeted donation, and responsible disposal. The system is not perfect – some of the recycling methods are so sensitive that a single piece of down on an otherwise recyclable polyester shell can render it too contaminated to process. Still, textile recycling has come a long way. “You could probably recycle almost anything at a cost,” Eleiter said. “But the cost is a part of it that has to be included.”

If a brand doesn’t properly invest in recycling, or doesn’t take back items that can’t be resold, the most likely destination for those items is an overseas landfill. Americans give away clothes at such a rapid pace that there are more “donations” than can be recirculated in the U.S. This contributes to the mass exportation of the world’s discarded clothes to the Global South. In Ghana, where dealers buy clothes by the bale to sell in markets, fifteen million garments arrive each week. The items that don’t sell in those markets wind up in landfills.

Then there is the question of whether selling used clothes actually reduces a company’s footprint. “A truly sustainable resale program enables the brand to make fewer units of new things because they’re selling more units of used,” said Cohen. No clothing company has publicly committed to doing that.

Finally, store credits can be problematic if they only encourage customers to buy more new stuff. Store credits incentivize customers to bring in their clothes, which is crucial to maintaining a steady supply of used items to sell. But not every program allows the customer to turn around and use that store credit on another used item. Patagonia, Arc’teryx, and Eileen Fisher offer options to spend the credit on both new or used clothing. But other brands offer no such option. Madewell, for example, will give you a $20 credit for turning in used jeans of any brand, but it can only be spent on their secondhand site. Store credits can’t be used on lululemon’s secondhand site, which the company said was because the program is still in a pilot phase. RaaS, a white label resale service run by thredUP, has big clients like Abercrombie & Fitch, adidas, and Gap, but doesn’t offer an option to spend credits on secondhand items.

“The whole point of recommerce is to prevent people from buying new clothes,” said Marilyn Martinez, a circular economy expert at the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, “but if you’re giving people a discount to buy more new stuff, it defeats the purpose.”

So, to thwart the fashion industry’s environmental recklessness, do we all need to be like the man from the Berkshires, and not buy a single new item ever again? Maybe – but that’s not necessarily realistic. A significant chunk of the global economy is built on manufacturing and selling new clothes, the infrastructure required for a more circular production model is very far from where it needs to be, and the simple premise of wearing someone else’s old clothes is still an uncomfortable concept for many people. But as that paradigm begins to shift, what we can do is get in the habit of trying used first. When you need a new pair of jeans — peruse Levi’s secondhand shop before clicking over to the new selection. Maybe you’ll always prefer to buy your pants new, but are open to donning a used parka. Look for the places where used works for you, and over time, you might find more of them.

Resale can’t solve fashion’s environmental problem on its own. It will have to be paired with other means of recirculating clothes, including repair, rental, and recycling. New clothes will need to be made from recycled and regenerative materials, manufactured and transported with renewable energy. The amount that Americans buy won’t change soon, but what we buy might. “I don’t see a world where people don’t want to wear new stuff,” Martinez said, “but I see a world where the ‘new stuff’ feels new for you, but doesn’t have to be from new resources.”

Editor’s note: Patagonia is a donor and advertiser with Grist. Financial sponsors have no role in Grist’s editorial decisions.

*Correction: The quantity of Arc’teryx’s discount on refurbished jackets has been corrected.