This story was co-published with Public Health Watch and Houston Landing.

People living on the east side of Harris County, Texas, have an unlikely bond with residents of Berre-l’Étang in southern France: They all inhale toxic chemicals from plants owned by LyondellBasell, one of the world’s largest petrochemical companies.

In the summer of 2020, LyondellBasell’s 2,471-acre industrial complex in Berre-l’Étang had more than half a dozen major incidents in which flares released large amounts of chemicals into the air. Thick clouds of smoke drifted over the community of 14,000. The flares burned so brightly, photographs show, that the normally pitch-black night was replaced by what looked like a prolonged sunset. The smoke carried benzene and other toxic substances to Marseille, France’s second-most-populous city, 10 miles away.

A year later in Texas, two major chemical releases at LyondellBasell facilities in Harris County forced residents of Jacinto City, Galena Park, and neighboring towns to shelter indoors. One of those incidents killed two workers and sent dozens to area hospitals.

Last year Public Health Watch and the Investigative Reporting Workshop examined LyondellBasell’s record in Harris County, and that project made us curious about the company’s performance outside the United States. We chose to look at Berre-l’Étang because both it and Harris County are at the center of their countries’ petrochemical industries — and both struggle to balance the economic benefits they gain with the concerns of residents who are breathing noxious fumes.

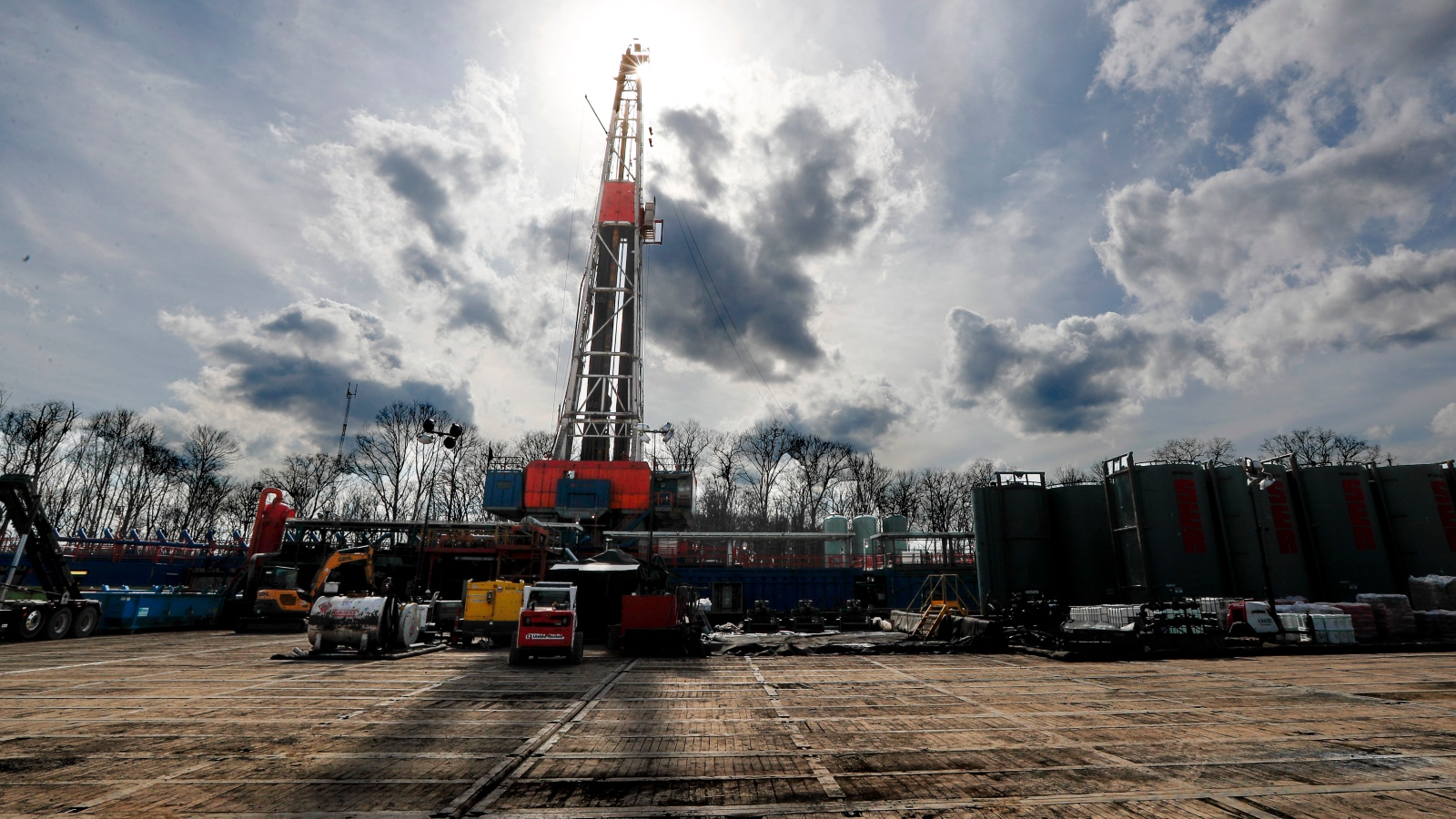

In eastern Harris County, 10 oil refineries process 2.6 million barrels of crude oil a day, and thousands more facilities store or manufacture the chemicals the industry uses and produces. Petrochemical plants loom over houses and playgrounds. A terminal holding millions of barrels of chemicals is seven blocks from a middle school.

Berre-l’Étang lies in one of the most heavily industrialized areas of France, where it and nine other towns surround a 60-square-mile lake, Étang de Berre. A 2017 study of some of those towns found that 63 percent of the population had at least one chronic disease. The French national average is 37 percent.

Local officials in France appear to have even less power to deal with industrial emissions than those in Texas, where state regulations are notoriously lax. Activists in both countries complain that regulators prioritize the economic well-being of polluting industries over the environment and public health.

In 2018, Éliane Jurado, a retired teacher living in Berre-l’Étang, created a citizens platform, LibAIRté, pledging to “defend the air quality of my grandchildren until my last breath.” LyondellBasell’s 2020 flaring — a process that burns off excess gas and relieves pressure — galvanized support for the movement and forced the city government to organize a town-hall meeting.

But in the end, Jurado says, nothing happened. She left Berre-l’Étang in 2021 and is still looking for someone to take over LibAIRté’s Facebook group, which at one point had 1,300 members.

A LyondellBasell spokesperson said the company declined to comment for this story.

The LyondellBasell facility has been a fixture in Berre-l’Étang since 1934, and authorities have known for years that it emits high levels of cancer-causing chemical agents such as benzene and 1,3-butadiene. The enormous industrial complex hosts one of the world’s largest olefin steam crackers, a butadiene extraction unit and polypropylene and polyethylene plants. It produces chemicals that are used in consumer products, like food packaging, furniture, automobile parts, construction materials, and toys.

LyondellBasell acquired the facility in 2008, a year after Leonard Blavatnik, a secretive, Soviet-born billionaire, combined U.S.-based Lyondell Chemical and Netherlands-based Basell Polyolefins to form LyondellBasell. The company has been based in Houston since then.

According to an article in New York Magazine, after Russia invaded Ukraine, Blavatnik came under scrutiny for his past ties with the Soviet Union but hasn’t faced any significant repercussions. He retains the largest share in LyondellBasell Industries, which is traded publicly on the New York Stock Exchange, via his holding company Access Industries.

LyondellBasell operates more than three dozen chemical facilities in Europe, including many with a history of pollution incidents. But none has been as life-altering as the plant in Berre-l’Étang, where it dominates local politics, people’s livelihoods and public-health discourse.

A database maintained by France’s Ministry for Ecological Transition and Territorial Cohesion shows that between 2008 and August 2022, the complex recorded more than 150 incidents, including flaring and fires, gas leakage, and power failures.

For years, studies conducted by French government scientists concluded that the health of people living in the industrialized communities that surround Étang de Berre isn’t much different from the health of people in other parts of France. A 2012 study by the Institute of Health Surveillance, a government agency that has since been merged into the National Public Health Agency, reached that conclusion using hospitalization data for cardiovascular disease, respiratory illness, and cancer. The data only records severe health issues.

But in 2017, a group of U.S.-based public health researchers collaborating with independent French scientists reached a very different conclusion after conducting the first community-based participatory survey on residents’ health.

Instead of being restricted by the limitations of hospitalization data, they knocked on the door of every fifth residential unit and asked people directly about their health. Using that data, they found that residents of the industrialized area were dramatically less healthy than people in France as a whole.

About 12 percent of residents had been diagnosed with cancer, while estimates for the national average ranged from 4-6 percent at that time. Diabetes patients constituted about 13 percent of the region’s population compared with 5 percent nationally. Asthma and skin conditions were even more common.

“This means that residents in this industrial zone are experiencing a higher burden of health issues than others in their region or France as a whole,” Alison Cohen, an epidemiologist with the University of California, San Francisco, who co-led the study, told Public Health Watch in a recent email.

Cohen’s interest in the region dates to 2011 when, as a Fulbright grantee, she studied the European Union’s approaches to regulating chemicals compared to the process in the United States. In 2015, along with an American and a French colleague, she published a report that analyzed three state-funded studies, including the 2012 study, and found that the previous reports didn’t reflect the public’s lived experiences.

Residents “were not included in designing those studies, and many felt that their questions were not addressed and thus the findings were not relevant, or believable, to them,” Cohen’s later study noted in 2017. “There were also several studies that either never concluded and/or never fully released findings to the public. Distrust and frustration regarding professionally driven health studies was high in this industrial zone.”

Cohen and her colleagues designed their research to answer the most pressing questions the residents had about their health. They worked with community members at all stages of their research, including its design and interpretation.

Their findings instantly made headlines and spurred a wave of environmental activism that put France’s Public Health Agency on the defensive.

Stacy Algrain, a climate-justice activist who grew up in Berre-l’Étang, focused on the report in a campaign she organized against LyondellBasell. While studying environmental policy at Sciences Po, Paris, one of the country’s most prestigious institutions, she founded Penser L’après, an organization aimed at educating the public about a range of issues, from climate change to pluralism to patriarchy.

Algrain says her values were shaped by her upbringing in a town overshadowed by the towering stacks of the LyondellBasell plant.

“I grew up here. I know every corner of this lake, its richness, and its beauty, but when I say the name of my city, the answer is, ‘Ah, OK, the city with the factories and the chemical smell?’” she wrote on Twitter in September 2020. “[I’m] chronically ill for 5 years, and although the link [of the illness] with my surroundings may be difficult to establish, I do not want another person, another child to hear this as well.”

In the neighboring town of Fos-sur-Mer, the study by Cohen and her colleagues inspired about 100 residents to file a criminal complaint that referenced several major factories, including one owned by steel giant ArcelorMittal, which, in 2016, released 23.5 tons of benzene from its Fos-sur-Mer factory, according to the newspaper Le Monde. It also stirred separate civil lawsuits that targeted ArcelorMittal and two other companies. LyondellBasell, which has a 133-acre plant in Fos-sur-Mer, was not mentioned in the lawsuits.

The criminal complaint is unprecedented in France, where courts have never been asked to impose criminal liability on industries for pollution that may harm public health. In the past, workers generally accepted the health risks in exchange for high salaries, Julie Andreu, the attorney representing the Fos-sur-Mer residents in the lawsuits, told Public Health Watch. But as the incidents have become more frequent, she said, they “are less and less accepted by the population.”

ArcelorMittal, whose annual revenue was $79 billion last year, has faced relatively modest penalties.

In a 2018 civil lawsuit it was fined the equivalent of about $16,000 for releasing excessive amounts of benzene. Andreu said the company was also fined about $1,600 a day — for a total of $299,000 — until it complied with the European Union’s benzene standards six months later.

An investigation by Marsactu, a regional news outlet, later revealed that French labor inspectors had found that employees at the site had been exposed to benzo(a)pyrene at a level 32 times higher than European Union standards allow. Benzo(a)pyrene is an extremely toxic hydrocarbon that can affect the nervous, immune and reproductive systems.

In March this year, Disclose, a nonprofit newsroom in France, obtained documents showing that two of ArcelorMittal’s steel plants — one in Dunkirk and the other in Fos-sur-Mer — account for 25 percent of France’s industrial pollution and exceeded French and European pollution limits for more than 200 days in 2022. In June authorities ordered ArcelorMittal to temporarily shut down its Fos-sur-Mer site due to dust exposure and toxic chemical release. Days later, a judge reversed the order, arguing that the immediate shutdown would “seriously undermine the freedom of trade and industry.”

Most of the citizen complaints against ArcelorMittal were dismissed by a judicial court, although Andreu is appealing that decision. One of the complaints involved Sylvie Anane, a Fos-sur-Mer resident who had died a year earlier from several cancers and cardiovascular conditions. In the order rejecting another case, a judge was quoted in a newspaper as saying that ArcelorMittal’s emissions were acceptable given “the consideration constituted by national industrial development.”

The judge also said residents had accepted “the foreseeable risk linked to the pollution by industrial activity” when they chose to live close to the industries.

“Basically, the judge blamed residents for pollution by saying, ‘You had it coming,’” said Algrain, the activist. “Others are saying if you’re not happy with the way you’re living or the living conditions, you can just leave.”

The remaining cases against ArcelorMittal and the other factories are pending. Public Health Watch reached out to ArcelorMittal but has not received a response.

Andreu said several residents recently asked her to file a separate administrative action against the French government for negligence.

“We believe the state, which is aware of the risks, has not acted on its own findings and has exposed the population to risk,” she told Public Health Watch.

The public outrage over ArcelorMittal in 2018 helped fuel a similar outcry over LyondellBasell’s persistent emissions.

Activists in Berre-l’Étang led by Éliane Jurado and her group, LibAIRté, joined the organization that had helped mobilize the Fos-sur-Mer lawsuits. By 2020, flaring in the LyondellBasell factory in Berre-l’Étang was so common that even residents of neighboring towns were outraged. Several mayors wrote a joint letter, threatening LyondellBasell with a similar lawsuit. Eric Le Dissès, the mayor of Marignane, asked President Emmanuel Macron to initiate a state investigation into the pollution incidents, according to a newspaper report.

“One municipality attacking an American company such as LyondellBasell would be like David against Goliath,” said Stéphane Le Rudulier, one of the mayors. “So we unified to send a common message so that we are taken seriously.”

Notably absent in the crusade against LyondellBasell was Mario Martinet, the mayor of Berre-l’Étang. LyondellBasell is by far the city’s largest employer, with 1,300 workers. It contributes the equivalent of about $369 million to the local economy each year.

Instead of signing the joint letter, Martinet called for talks and meetings with the petrochemical giant and local stakeholders. At one of those meetings the mayor shared the stage with his deputy, Marc Campana, who oversees the city’s environment portfolio. Campana, a labor union leader, worked for LyondellBasell at the time.

The meeting became contentious, according to news reports.

“My son has cancer, my husband contracted a serious blood disease, and my daughter has inflamed eyes,” one woman said.

“I live under the torch,” another said, referring to the giant flares. “The noise level is intolerable. I could not enjoy my summer outdoors. For days, we found a yellowish deposit at home.”

One of the LyondellBasell officials at the meeting, Sébastien Mathiot, argued that the company had invested heavily in reducing emissions and that the emissions rate had drastically decreased since 1980.

Eric Mesle, the plant’s operations manager, promised that flaring incidents like the ones the city experienced “should never happen again in the years to come.”

But less than two months later, a new round of flaring at the plant continued for two days and could be seen miles away.

Algrain, the climate activist who grew up in Berre-l’Étang, said the meetings were meaningless.

The political leaders basically “make it look like they really ask the industrial companies to change their behavior, but it appears to me that they are on the same side,” she said.

“From what I saw, it was just a lot of speeches. The discourse in these meetings, it’s always the same: ‘Don’t worry — it has no impact on your health, and it’s going to be OK.’”

Public Health Watch reached out to Mayor Martinet for comment but has not received a response.

In January 2022, LyondellBasell’s Berre-l’Étang facility had another major incident. Its steam cracker unit caught fire and released a huge plume of blackish smoke that a local newspaper said was visible for hours.

The company announced it would invest more than $163 million to modernize the facility, reducing CO2 emissions by 37 percent — or 30,000 tons — per year. It estimated the work would be completed in less than three months.

During the construction period, there were multiple flaring and fire events, which the company attributed to maintenance and shutdown of the plant.

But in June 2022 — after the renovation was complete — residents were awakened by the raucous sound of a siren at the plant. The company told town leaders that its siren system had malfunctioned and the situation was under control.

But some residents disagreed, commenting on Facebook that they feared harmful chemicals had been released. One woman posted snapshots of findings from air quality monitors installed by AtmoSud, a local environmental organization. They showed spikes in benzene levels at that time.

“Considering how unbreathable it was and that it stung the eyes, I doubt very much that the benzene was not very dangerous,” another commented.

Two months later, there was a fire at the site, originating from an oil pump.

Another fire broke out in April of this year on the plant’s steam cracker. Flares and smoke could be seen outside the site. The company said at least one employee had been injured.

Back in Harris County, Texas, three facilities owned by LyondellBasell have had at least 17 air “emission events” since Jan. 1 of this year, according to a Public Health Watch review of reports maintained by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality. Some lasted only a few minutes, according to the company’s reports to the state agency. Others went on much longer: 15 hours, 27 hours, 56 hours, 69 hours. Chemicals released included sulfur dioxide, which attacks the respiratory system; hydrogen sulfide, a gas that can be deadly in high concentrations and causes eye, throat and nose irritation at low levels; and carbon monoxide, which in sublethal doses can cause headaches, nausea and rapid breathing.

LyondellBasell has been trying to sell one of the problematic facilities, Houston Refinery, which was responsible for a 2021 chemical release that forced thousands of people to shelter in their homes. After two attempted sales failed, the company announced that it would close the 100-year old refinery by the end of this year due to the cost of overhauling it. According to Reuters, analysts estimated that the facility would require about $1 billion in upgrades to continue operations.

In May, however, LyondellBasell announced that it would postpone the closing until 2025 and increase plant capacity to 95 percent, up from 85 percent in the first quarter of 2023.

“Favorable inspections and consistent performance have given the company confidence to continue safe and reliable operations at the Houston site,” LyondellBasell said in a statement on its website. The company said it anticipates spending “moderate” amounts of money on maintenance in 2023 and 2024.