When Chief Dsta’hyl arrived on a Saturday morning in October, the big construction vehicles rumbled back and forth over the cold mud. He watched an excavator dig into the soil, its yellow, hydraulic arm moving against the green backdrop of forests that he has called home all his life.

The area that was being prepared for construction lies within the territory of the Wet’suwet’en, a First Nation in what is currently called British Columbia, Canada. As a supporting chief from the Likhts’amisyu clan, Dsta’hyl had been tasked with enforcing Wet’suwet’en law in the area.

The scene he was witnessing — construction crews preparing to build a pipeline through Wet’suwet’en territory, without their consent — represented a blatant violation of those laws. And Dsta’hyl had seen enough. After warning the on-site construction managers that they were trespassing, he arrived the next day and approached a pair of orange-vested security subcontractors employed by TC Energy, the company building the fracked gas pipeline known as Coastal GasLink, or CGL. He notified them that he would be seizing one of their excavators and then stepped onto the hulking vehicle and disabled it by disconnecting its battery and other components. Though he planned to leave the vehicle in place, Dsta’hyl said he wanted to make a statement to the company, which the traditional leaders decided to evict from their territory last year.

In a video posted on social media, one of the security workers asks Dsta’hyl what he wants from them. He lets out a hardy laugh.

“For you guys to leave,” he says.

In another clip, Dsta’hyl stands on the vehicle as the workers below angle camcorders at him. “You guys are trespassing, and we want to make sure that you guys know that we mean business.”

The crew members abandoned the area shortly after, driving off in their pickup trucks and construction vehicles — short one large piece of machinery. And while Dsta’hyl had gotten his message across, the asset-seizure was short-lived.

“In the middle of the night, they stole that one back,” he said.

That incident was one of the latest standoffs between the Wet’suwet’en and Coastal GasLink over the proposed pipeline, which, if completed, would carry 2 billion cubic feet per day of fracked gas from northeastern B.C. to a proposed processing facility on the Pacific coast. Although the company says it received all necessary permits and approvals to build the pipeline, the hereditary chiefs of the five clans of the Wet’suwet’en First Nation contend that because they never gave the company permission to build on their territory, the construction efforts violate their laws — not to mention Canada’s own laws.

The tribe organizes itself into five clans, each of which is subdivided into multiple “houses.” The house chiefs oversee specific areas within the tribe’s traditional territory, which encompasses roughly 22,000 square kilometers (8,500 square miles). The hereditary chiefs make decisions that govern their territory.

“It’s quite an intricate governance system,” Dsta’hyl said, adding that the Wet’suwet’en have been practicing these laws for thousands of years.

The Wet’suwet’en government was recognized in a 1997 ruling by the Supreme Court of Canada, which held that the First Nation had never given up rights or title to their lands. And, like other First Nations in Canada’s westernmost province, the Wet’suwet’en never signed a treaty with the British Crown nor the Canadian government, meaning their territory is unceded land.

“They never surrendered or ceded their territory, so what they’re dealing with is this incursion by pipeline companies and police who are basically invading,” said Clifford Atleo (Tsimshian, Nuu-chah-nulth), an assistant professor of resource and environmental management at Simon Fraser University whose work focuses on Indigenous governance.

“What the Wet’suwet’en are doing is protecting their lands,” Atleo said.

Fearing the destruction of their territory, as well as harmful impacts to water, wildlife and people, some members of the Wet’suwet’en have taken direct action against a slew of proposed pipelines over the past decade. They have created dozens of checkpoints and blockades to prevent construction crews from accessing Wet’suwet’en lands and significant sites. In 2009, members of the Unist’ot’en clan established a checkpoint near a small bridge that leads onto their territory, which they maintained alongside Indigenous and non-Indigenous allies for more than ten years. Another blockade was later built on the same road in the neighboring Gidimt’en territory, where, in January 2019, a series of police raids drew international media attention.

Donning tactical gear and armed with military-style rifles, officers stormed the Gidimt’en checkpoint, arresting 14 land defenders as the officers dismantled the camp. Documents obtained by the Guardian suggest that the officers were prepared to use lethal force against Wet’suwet’en land defenders during the raid.

A year later, the Unist’ot’en camp was raided by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, or RCMP. Several people were arrested in the 2020 raid, during which officers sawed through a wooden barricade with the word “RECONCILIATION” painted on it, clearing the way for CGL crews to build on Wet’suwet’en territory.

Both incidents sparked renewed controversy regarding the tactics the RCMP employs in suppressing protests, with many critics highlighting the agency’s history of using excessive force against Indigenous land defenders as well as violent, anti-Indigenous sentiments among its ranks. The RCMP asserts that the raids and ongoing patrols in the area are necessary to enforce a court order that prohibits protestors from blocking CGL construction. A provincial court handed down the injunction three years ago, and, in the time since, both the RCMP and the company have used the legal ruling to restrict access to certain areas and to arrest land defenders who stand in the way of the project.

But Indigenous people have continued to resist the pipeline, using tactics that escalated over the weekend, when members of the Gidimt’en clan demolished a section of road that CGL has used to access Wet’suwet’en territory.

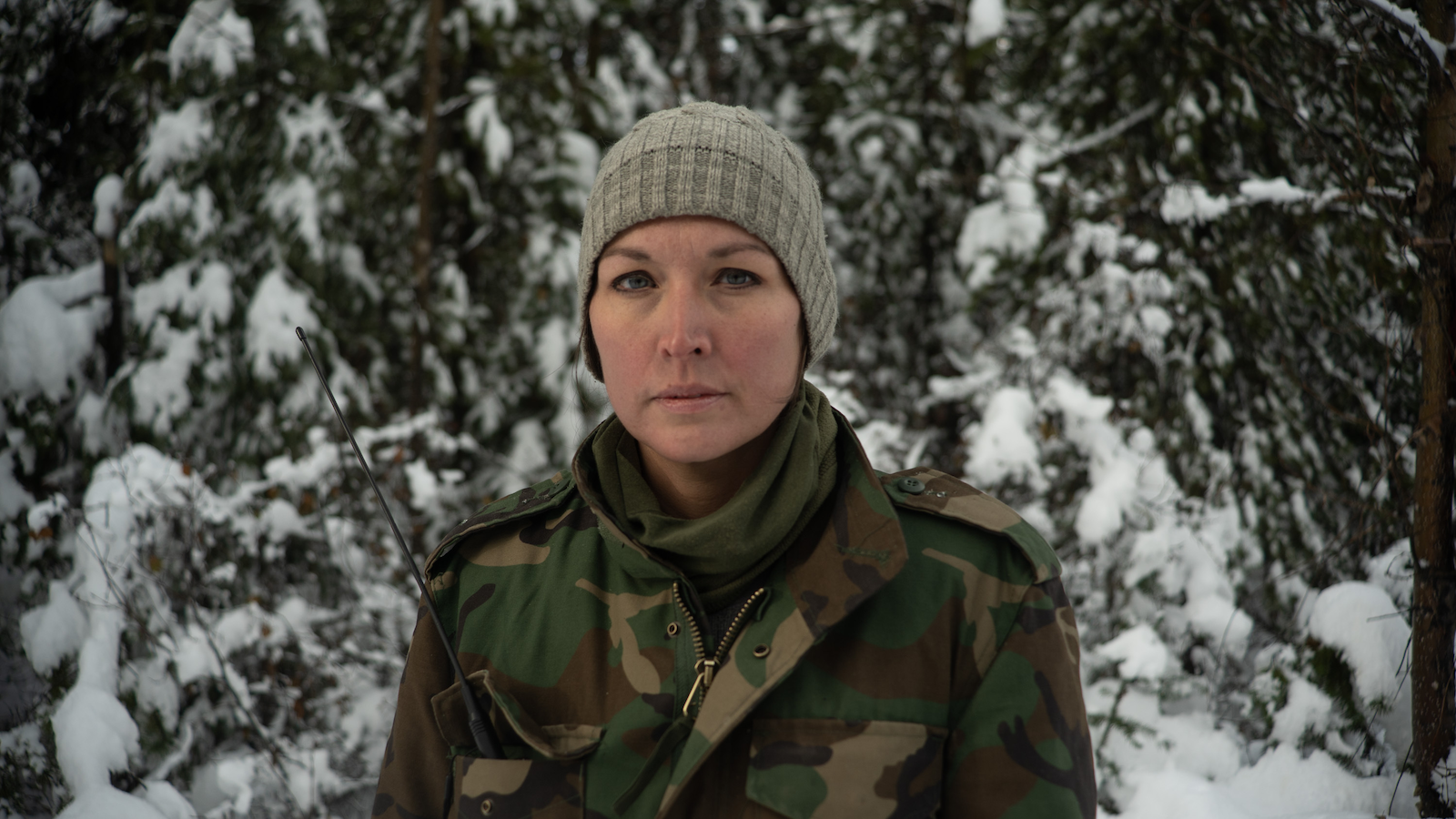

On Sunday morning, CGL employees and subcontractors were given an immediate evacuation order. “You have eight hours to vacate the territory peacefully,” said Sleydo’, a supporting chief from the Gidimt’en clan, who made the announcement over the radio. “Failure to comply will result in immediate road closure.”

But land defenders saw little movement along the road — even after the company negotiated for a two-hour extension. When members of the group approached a man camp they had ordered to disband, they discovered construction crews were not preparing to leave, and had positioned multiple construction vehicles and machinery on the road, said Jennifer Wickham, a member of the Gidimt’en clan who serves as media coordinator for the group.

In response, land defenders seized a CGL excavator and destroyed a segment of the roadway before dropping a crumpled minivan at a bridgehead. Wickham said that, given RCMP’s previous enforcement of injunctions, a police raid may be imminent.

“We absolutely expect them to do that,” she said. “As far as when, we have no idea.”

In an email, an RCMP spokesperson said the agency “is aware of the protest actions and we have, and will continue to have, a police presence in [the] area conducting roving patrols. No arrests were made and we continue to monitor the situation.”

The hereditary chiefs of the Wet’suwet’en say the injunction, RCMP’s enforcement of it, and the project itself represent an affront to First Nations sovereignty, pointing to the 1997 Supreme Court decision as proof that they have the constitutional right to expel CGL from their territory.

In what is known as the Delgamuukw case, the court confirmed that “Aboriginal title is a right to the land itself” based on occupation of the area and a system of law that predates British and Canadian colonization. The Supreme Court decision left many issues unresolved, though, such as the exact boundaries of the tribe’s traditional territories.

Despite the house chiefs’ legally recognized authority, the pipeline company never engaged in meaningful consultation with them, Sleydo’ said.

“They will send information, but they don’t actually give us the opportunity to engage with that information, and when we have responded, they disregard everything we say,” she said. “That’s not consultation and it’s definitely not consent.”

The company frequently states that it received approval from the Wet’suwet’en because it negotiated an agreement with the tribe’s elected band councils. Imposed by the Canadian government under the Indian Act of 1876, the band-council system was created to facilitate interactions between First Nations and the federal government. The councils are considered the governing bodies for their respective First Nation reserves, and elected representatives from 20 band councils along the pipeline route signed so-called “benefit agreements” with the company to allow construction. Although councils from multiple reserves within Wet’suwet’en territory approved the project, the hereditary chiefs — as representatives of older, traditional styles of government — say they retain authority over their traditional lands, and that CGL needs their permission to access the territory.

The company claims it has sought numerous meetings with the hereditary chiefs in the past two years, and that it continues to seek input from Wet’suwet’en leaders “with the sincere hope of developing a respectful and constructive relationship as we move to completion of the Project and beyond.” In an email, CGL spokesperson Natasha Westover cited safety concerns as justification for blocking Wet’suwet’en people from their territory.

“Coastal GasLink has an obligation to facilitate access for [I]ndigenous peoples to their traditional territories, however, that access may be delayed where it is unsafe [to] provide access immediately,” she said. Westover declined to provide an interview with CGL executives or other personnel for this story, despite multiple requests.

After CGL’s injunction was made permanent last winter the Wet’suwet’en house chiefs unanimously decided to evict the company from its territories.

Flowing from a glacier-fed lake, Wedzin Kwa runs through the heart of Wet’suwet’en territory. The river provides important spawning grounds for salmon, and supplies community members with unpolluted drinking water.

“You could swim in that lake and just open your mouth and drink the water, it’s so pristine,” Sleydo’ said. “And the river is so clear that you can see these very deep spawning beds that the salmon have been returning to for thousands of years.”

CGL plans to construct the pipeline beneath the river. In September, when members of the Gidimt’en clan heard that construction crews were preparing to tunnel under Wedzin Kwa, they rushed to occupy the site. They have since erected several structures, including a cabin with a full kitchen and multiple solar-powered “tiny homes.”

Because the conflicts with RCMP in recent years have escalated in the dead of winter, the Gidim’ten clan has experience erecting blockades in temperatures as low as minus 40 degrees Fahrenheit, and welcomed the chance to set up camp with only a light snow in the ground.

“Blockade season came early this year,” Sleydo’ said.

Despite the mounting tensions, Sleydo’ said the members of camp try to remain upbeat, laughing and telling stories around the campfire at night.

But the mood changes when the RCMP approaches the area. In the days after the outpost was established, RCMP officers tasered a person and injured a man who had locked himself to the underside of a bus. Sleydo’ said officers grabbed the man by the legs and repeatedly lifted his body and slammed him onto the ground as a way of forcing him to unclip himself from the vehicle. She said the RCMP’s use of “pain compliance” equates to torture.

“That person is still receiving ongoing medical care and has [nerve damage] in his hands,” she said.

The national police force frequently sends members of a specialized division with a reputation of using excessive force against protestors. Known as the Community-Industry Response Group, or C-IRG, the roving unit draws RCMP officers from far-flung areas of Canada to break up protest camps that form in opposition to pipelines, mining projects and logging operations.

Officers with the unit have been widely criticized in recent months for their aggressive tactics in breaking up anti-logging protests near Fairy Creek on Vancouver Island. In addition to making violent arrests and showering unarmed protestors with pepper spray, many of the officers removed all forms of identification from their uniforms during multiple raids. British Columbia Supreme Court Justice Douglas W. Thompson condemned those actions in his decision to end an injunction against the Fairy Creek protestors, writing that RCMP’s enforcement tactics “have led to serious and substantial infringement of civil liberties.”

During RCMP raids on Wet’suwet’en territory, officers often brandish sniper rifles and bring in police dogs to intimidate land defenders, Sleydo’ said. “If we’re trying to defend a space, we’re considered a huge threat,” she said. “And they use that as an excuse to use violence and excessive force against us.”

The agency’s media relations team did not provide a phone interview despite multiple requests.

Miles Howe, an assistant professor of critical criminology at Brock University, said the RCMP often engages in “political policing,” in that the agency targets groups that are considered threats to Canada’s access to natural resources — and, by extension, the economic interests surrounding the extraction of those resources. Howe co-authored a 2019 report that used documents obtained through records requests to show that the RCMP performed extensive surveillance of Indigenous land defenders and assessed the risk posed by protestors not based on criminality, but on their ability to rally public support.

The RCMP raids in early 2020 sparked nationwide protests in Canada, leading Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to voice tepid support for Wet’suwet’en sovereignty, though he later demanded that the “barricades come down.” Months later, federal and provincial government officials agreed to engage in land-rights negotiations with the hereditary chiefs.

“So far, nothing has come from that process,” said Jennifer Wickham, who serves as media coordinator for the Gidimt’en resistance group.

Instead, the Canadian government has subsidized Coastal GasLink and continues to tout the benefits of liquified natural gas as a “transition fuel” that will set Canada on a course to reach its ambitious climate goals. Earlier this month, Trudeau took the stage at the UN climate change conference in Scotland to outline Canada’s plan to cap oil and gas emissions in order to reach net-zero emissions by 2050.

“That’s no small task for a major oil and gas producing country,” he said.

But critics say Trudeau’s commitments run counter to his administration’s support of natural gas projects, which have been shown to leak large amounts of methane — a powerful greenhouse gas — into the atmosphere. Given the outsize impacts climate change often has on Native communities, Indigenous rights advocates say it is critical that First Nations are adequately consulted on resource-extractive projects that take place on their ancestral lands.

In 2014, the UN’s special rapporteur on the rights of Indigenous peoples implored the Canadian government to seek the “free, prior and informed consent” of First Nations in the early stages of a project. The U.N. Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples states that Natives “have the right to own, use, develop and control the lands, territories and resources that they possess by reason of traditional ownership” and that they “shall not be forcibly removed from their territories.” Earlier this year, legislators passed a bill aimed at implementing UNDRIP into Canadian law.

And yet, the government is enabling Coastal GasLink to push its pipeline through Wet’suwet’en territory.

Sleydo’ said the group is “digging in for winter,” and has no intention of allowing the pipeline to cross Wedzin Kwa. The mother of three children said that, although it has been difficult being away from her family during the occupation, she refuses to pass the pipeline’s impacts down to her children.

“They will not drill under our sacred headwaters because we’re going to defend this space until the end,” she said. “We’re not going anywhere.”