Air pollution seems to gain another menacing nickname with every new study. Silent killer. Epidemic. Airpocalypse. The director of the World Health Organization has called it a “global public health emergency.” Recent headlines have declared dirty air a “pandemic,” maybe on the off-chance they will grab the attention of anxious people searching for news of the novel coronavirus.

The underlying message behind this wordsmithing is clear: It’s time to wake up to the consequences of polluted air, which is estimated to cut millions of people’s lives short each year. But are a bunch of breathless (no pun intended) metaphors and buzzwords enough to inspire action?

“It’s kind of hard to convey this story with the danger and urgency that it really merits,” said Beth Gardiner, the author of Choked: Life and Breath in the Age of Air Pollution. “It’s this thing in the background that we don’t really pay very much attention to.”

Gardiner compares breathing polluted air to eating junk food, because both take a toll on our overall health. “You wouldn’t think that the food you eat only affects your stomach,” she said. “We just know it affects our entire bodies.”

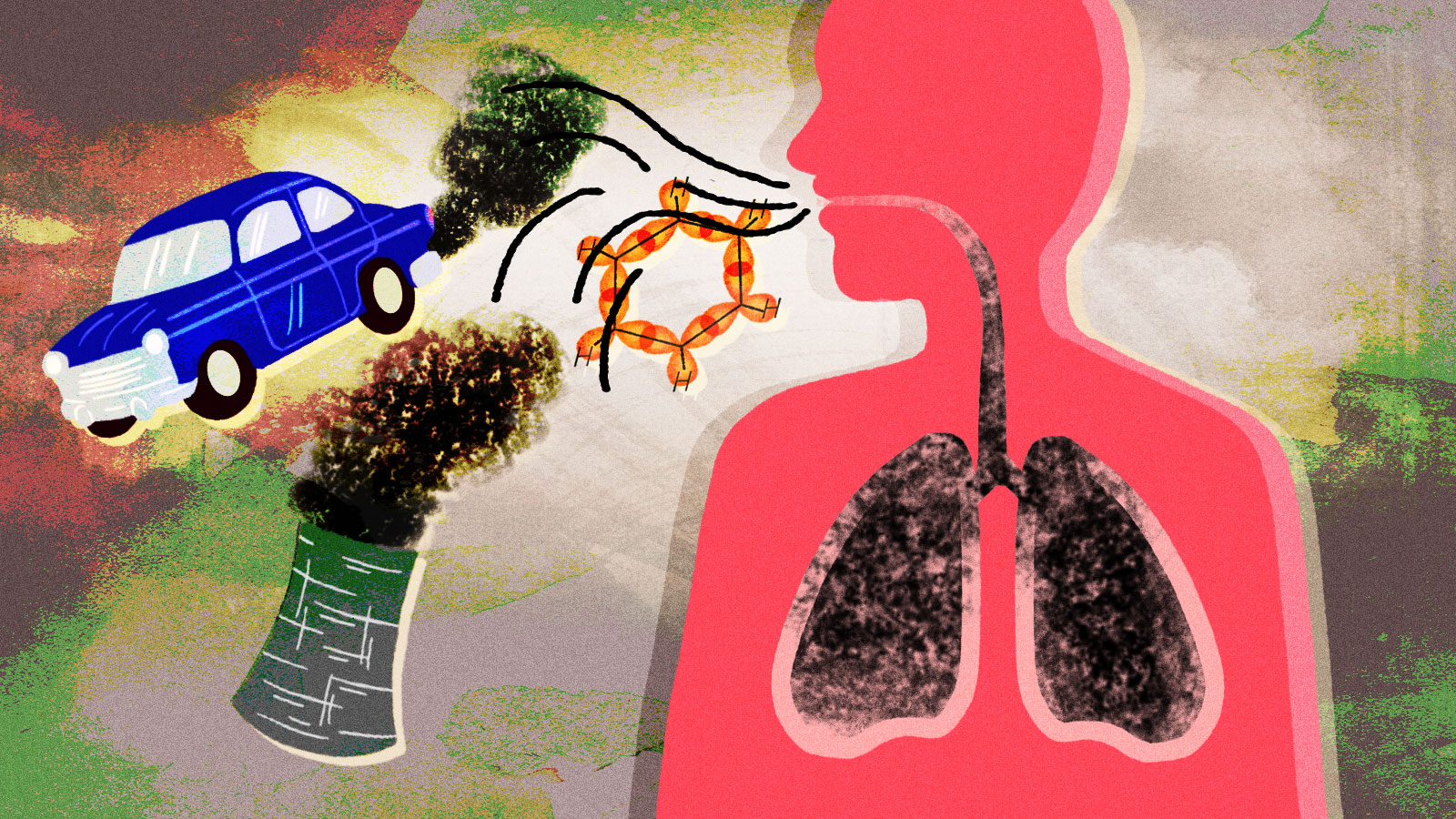

So does the ambient air we breathe, out on the street and inside our homes. It‘s thought to affect nearly every organ in our bodies — brains, livers, uteruses, and more — and has been linked to heart attacks, asthma, miscarriages, and numerous types of cancer. Estimates suggest that air pollution is a more potent killer than smoking. And it leaves hardly anyone untouched: An analysis from the World Health Organization found that more than 90 percent of people worldwide are breathing unsafe air.

There’s data to suggest that Americans are beginning to grasp how dangerous the situation is. But all this talk of silent killers and airpocalypses doesn’t seem to be fast-tracking efforts to clean up the air in the dozens of cities ranked among the most polluted in the country — like Los Angeles, Pittsburgh, and Houston — in the American Lung Association’s 2019 State of the Air report. Media reports highlight the dire statistics, but evidence suggests that putting a human face on the problem could be what’s needed to move people and governments to action.

According to a review last year of academic studies by Vital Strategies, a nonprofit in New York that works to improve public health, the media plays a “critical role in communicating health threats — particularly when those threats may not be immediately seen or felt.” Some evidence indicates that Americans are becoming more attuned to the deadly threat likely lurking in their air. In a 2018 survey by Southern California’s Chapman University, more people said they were afraid of air pollution than the prospect of another world war, economic collapse, or a terrorist attack. (Interestingly, it also stoked slightly more fear than climate change.)

So if Americans think that air pollution is scarier than terrorism, why aren’t they acting like it? Or, more importantly, why isn’t the government acting like it? After decades of steady improvement, air pollution is taking a turn for the worse in the United States. The culprits: more cars on the road, bigger wildfires, and the Environmental Protection Agency’s loosening of various regulations under President Donald Trump.

Pushing for stronger clean-air regulations might seem like a no-brainer — for most presidential administrations — but the politics are actually a little thorny, in part because of air pollution’s silent-killer status. We don’t always notice when it’s slowly hurting us, or even when air quality has dramatically improved, Gardiner said. That makes building the political momentum needed for regulatory or legal changes a tall order.

The United States has actually made a lot of progress on cleaning the air through regulations since the EPA’s founding by President Richard Nixon in 1970, but prompting renewed action might require something more than just concern. A good story helps. “Obviously, it’s a cliché to say that one person’s story is so much more powerful than a statistic,” Gardiner said. But there’s some truth to it.

In 2015, Chai Jing, a former television host in China, made a documentary called Under the Dome about air pollution. It wove Chai’s story about her newborn daughter’s health problems with investigative reporting on how companies and the Chinese government weren’t doing enough to stop pollution. The film was compared to Silent Spring and was viewed by 200 million Chinese in the three days after it was posted online; then it was taken down by the Chinese government. When a reporter subsequently asked Premier Li Keqiang, the country’s second in command, what the government was planning to do about the documentary’s accusations, Li acknowledged that the government had failed to protect its people and vowed to take big steps to stop pollution. (And it has).

Stories like Chai’s are powerful because they break through abstraction to make air pollution seem like a concrete, relatable problem, Gardiner said. She also pointed to the story of Rosamund Adoo-Kissi-Debrah, a vocal advocate in the United Kingdom. Adoo-Kissi-Debrah’s daughter, Ella, was only 9 when she died in 2013 after years of asthma attacks and seizures. (Many of her hospitalizations coincided with spikes in local pollution in the diesel-clogged part of London where they lived.) Now Adoo-Kissi-Debrah is fighting to get air pollution written as a contributing factor to her daughter’s passing on her official death certificate. She has won public support for the legal battle from Sadiq Khan, the mayor of London, who has worked to reduce air pollution and recently introduced a $65 million so-called Green New Deal to make the city carbon-neutral.

Calling air pollution a “pandemic,” as the authors of a widely covered study did last week, can certainly grab people’s attention. But making the danger feel real means folding all those big numbers and compelling language into a cohesive story focused on a person, something our brains are primed to understand.

“The difficulty is always putting a human face on it,” Gardiner said. “Because obviously the science and statistics are very important, but we don’t really connect to them on an emotional level. We seek stories to illustrate things like that.”