Sam Bliss is traveling from Seattle to London by bicycle and boat. Read the intro to his travels here.

Tieton, Wash. — population 1,200 — sits on a plateau just above the Yakima Valley. A decade ago, it was just another economically depressed American farm town, one more victim of the corporatization of agribusiness. Successful small to mid-size farms had virtually disappeared, along with most local enterprise.

Now, Tieton is a place for creative people to enact their visions. Almost by accident, an influx of creative enterprise is bringing a different kind of prosperity to this one-time fruit boomtown.

Thanks to a loose association of artists and artisans that have set up shop, Tieton now shines as a hopeful example for hundreds of struggling rural towns across the United States. A long-abandoned apple distribution center now hosts a letterpress studio, a metal shop, a versatile gathering space, and a lamp production facility. The 40,000-square-foot warehouse space gets transformed to host various community events throughout the year, from concerts to weddings to celebrations of the Day of the Dead. From one of many formerly empty storefront spaces in the town square, Paper Hammer produces and sells stationery, handmade books, and other printed creations using techniques from the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries.

In all, about a dozen small businesses make up Mighty Tieton. Not including the artisans from out of town, 17 people are employed and learning to make beautiful and useful things by hand — almost all of them locals (association’s handyperson and event organizer Jeremy Howell, my friend who hosted us in Tieton, is one of just three exceptions). Seventeen may not sound like much, but this podcast episode about the town points out that if a project were to employ the same proportion of Manhattan’s population, about 140,000 people would be put to work. It doesn’t take much exploration in Tieton to conclude that the maker scene is reviving the look and feel of the town.

It seems fitting that Neil and I rode into Tieton at the tired end of our third day of biking. Design professional Ed Marquand might never have set up shop in this place had he not punctured both bike tires riding over a patch of goathead thorns in an abandoned parking lot here back in 2005. What he found that day was an opportunistic artist’s dream: space to create.

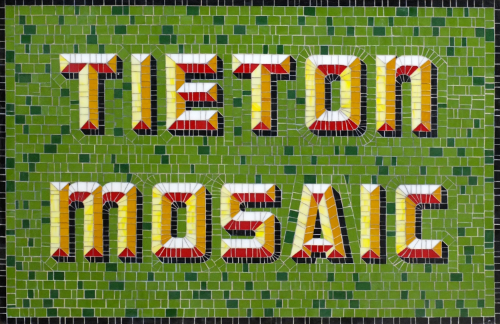

Marquand is the founder and leader of Mighty Tieton, an incubator for crafty projects and artsy businesses that operates out of the old apple distribution center and other buildings in and around town. Mighty Tieton’s associated nonprofit won a $50,000 National Endowment for the Arts grant to start a typographic mosaic studio in the warehouse. That money is being used not only to get the workspace built and supplied, but also to hire apprentices from the local high school to master the art of typographic tiling by hand, a craft that’s all but lost in the United States.

Marquand had always loved the handmade tile signage in the New York City subway. He learned that American businesses contract with Israeli and Italian families for that type of mosaic work, if at all. This realization lead to the birth of the Tieton Mosaic Project, which will use public spaces in the town’s small core — including the post office’s facade — as a showroom for the project’s handmade tile pieces.

A prototype from the Tieton Mosaic Project, which aims to create a striking visual personality for the small town. Tieton Arts & Humanities

Tieton’s revival story does raise some red flags. Think about it: Creative urban professionals come into an impoverished, rural place, buy a big chunk of it, and act out their artistic visions. Marquand says that a core group of about 10 creative entrepreneurs from Seattle dreamed up the idea for Mighty Tieton; they sat in the park in the center of town and played mental monopoly with empty properties. At the time, they were not consulting the town’s residents, a population that’s nearly two-thirds Latino, about their desires for Tieton.

“We liked that there were so many people in town who were looking for additional employment,” says Marquand. “They were looking to learn skills that they wouldn’t have learned otherwise, and they were looking to do things that were more engaging in terms of the imagination and creativity than most of the jobs in the area.” Since farms became bigger and fewer, unskilled orchard labor, fruit packing, and warehouse management were among the few jobs available to people in Tieton.

Ricardo Bautista tells me that the Spanish-speaking community has generally embraced the new opportunities brought by outsiders. “People are grateful; they want to do something different,” he says. Bautista and his wife, Linda, own the fantastic Mexican restaurant Central Bistro Café. The Bautistas have seen a recent uptick in both new customers and regulars. “For me and my family, I think it’s good,” saysBautista.

“The thing we recognized early on is the ones who are the most resistant to change are some of the old Anglos,” says Marquand. “They aren’t really going to be truly happy until the place reverts to what it was when they were in high school.”

A reversion to Tieton’s previous version of prosperity is unlikely, though. Through the middle of the 20th century, it was a classic farm town of the American West, with hardware stores, a movie theater, several cafes, a pool hall, a bowling alley, a grocery store, and other storefronts. The town’s economy revolved around the surrounding apple, peach, and pear orchards. Still does, but the fruit industry doesn’t provide good jobs or create vibrant communities like it used to, now that large corporations capture most of the benefits. “Even though fruit is more successful today, in this area, than ever, it’s also in the hands of very few people,” says Marquand. He thinks Tieton can be successful, “but it’s not going to be the same success.”

Tieton has the potential to be a model for how a community can transition from big business to small business. Across the globe, many other small communities face a similar crossroads. In fact, there’s a term for it: ”transition towns.” Transition towns are a network of municipalities building resilience for a post-fossil fuel world through self-sufficiency by creating community projects that feed and serve the community. Although Marquand sees the importance of a craft economy that benefits the town and its residents, he believes that producing goods and services for distant markets — rather than fostering independence through hyper-local enterprises — holds the key to Tieton’s future. “Trying to find a way to connect to the broader national economy is the only way many of these small towns are going to survive,” says Marquand.

And even though tiling mosaics with human hands isn’t as productive, in terms of output per hour, as operating a machine that does the same job, that may actually be a good thing for the environment. A machine gobbles up energy; if said machine relies on dirty energy, it creates carbon emissions. With ever-increasing automation and robotization, the dirty-energy economy continues to crank out more stuff each year than the year before — a lot of stuff we don’t really need. A greater reliance on handmade goods might slow down each worker’s production, which can keep folks employed without the climate-killing necessity of endless, exponential economic growth. People can do meaningful work while humanity as a whole uses less materials and energy. Of course, industries differ, and human laborers require fair wages and a safe working environment.

Still, replacing fossil energy with humanpower is a definite win for the climate. At least it makes me feel good to think that while traveling on a bicycle.

On our bike ride out of town, Neil and I stop by Tieton Farm and Creamery, a sustainable farm run by partners Lori and Ruth Babcock. Lori makes cheese by hand from a blend of sheep and goat milk. Ruth takes care of the animals. “I don’t know two women who work harder,” says Marquand.

The Babcocks, former software professionals from the Seattle area, purchased the property seven years ago. At the time, they wanted to open a bed-and-breakfast that served homegrown meals. The B&B plan fell through when the economy collapsed in 2008, but the Babcocks dug in and shifted to full-time farming. Today, they care for 70 sheep, goats, beef cattle, dairy cows, egg-laying hens, broiler chickens, ducks, and pigs. The grazing livestock moves about the grassland in several-week rotations, with portable fencing set up in new places every few days. Whey from milk production is fed to hogs that reside on a neighbor’s unused land. The Babcocks “pay” their neighbor with some pork each year.

Ruth Babcock introducing us to the residents of Tieton Farm and Creamery.Neil Baunsgard

As Ruth shows us around the farm and introduces us to its inhabitants, it becomes clear she loves rehabilitating and strengthening the farm’s ecosystem. “We are always bringing nutrients here. We don’t take them away,” she says.

The green meadow surrounding the farmhouse where cheese is produced was originally planted as white clover, alfalfa, and two kinds of grass. Now, dandelions and other plants that some farmers might call weeds have joined the multi-species field. Voracious goats are munching up some mustardy flowering plants when we walk up to meet the milk-producing mothers that get first dibs on each patch of grass. Ruth would love to add some shrubs and small trees to the grassland, but it’s hard to grow anything tall before the goats eat it.

At such a small scale, it takes a tremendous amount of effort to make ends meet, even selling artisanal cheese at farmers market prices. “I didn’t picture working seven days a week, every waking hour,” say Ruth. “The rules were written for big farms.”

In the days after we visited Tieton, Neil and I pedaled through more struggling agricultural communities in Eastern Washington, silver-mining boom towns that long ago went bust in the Idaho panhandle, and far-flung railroad outposts in Montana where signs that the 21st century has arrived are few and far between. Marquand challenged us to think about how these other depressed towns might be revived as we continue our bike travels. “There’s no easy, blanket solution,” he said. He’s right: How to best address a community’s struggles depends on site-specific attributes like the local ecology, geology, and culture.

It has been fun to imagine how these places might reclaim prosperity, creating wealth to share with each other rather than allowing it to be extracted by corporations. The people in rural areas continually overwhelm us with generosity along our journey, but they often aren’t optimistic about the prospects of revitalizing their communities

Yet what we have discovered — and what I wrote about in this post — is that rural folks’ caring attitudes create an informal sort of sharing economy where people simply look out for both friends and strangers. In many communities, the pieces are in place for a Tieton-esque revival. The question is, how can unemployed people and resources be put to work fixing problems in their communities without newcomers bringing capital to invest? Neil and I will keep this question in mind along the way.