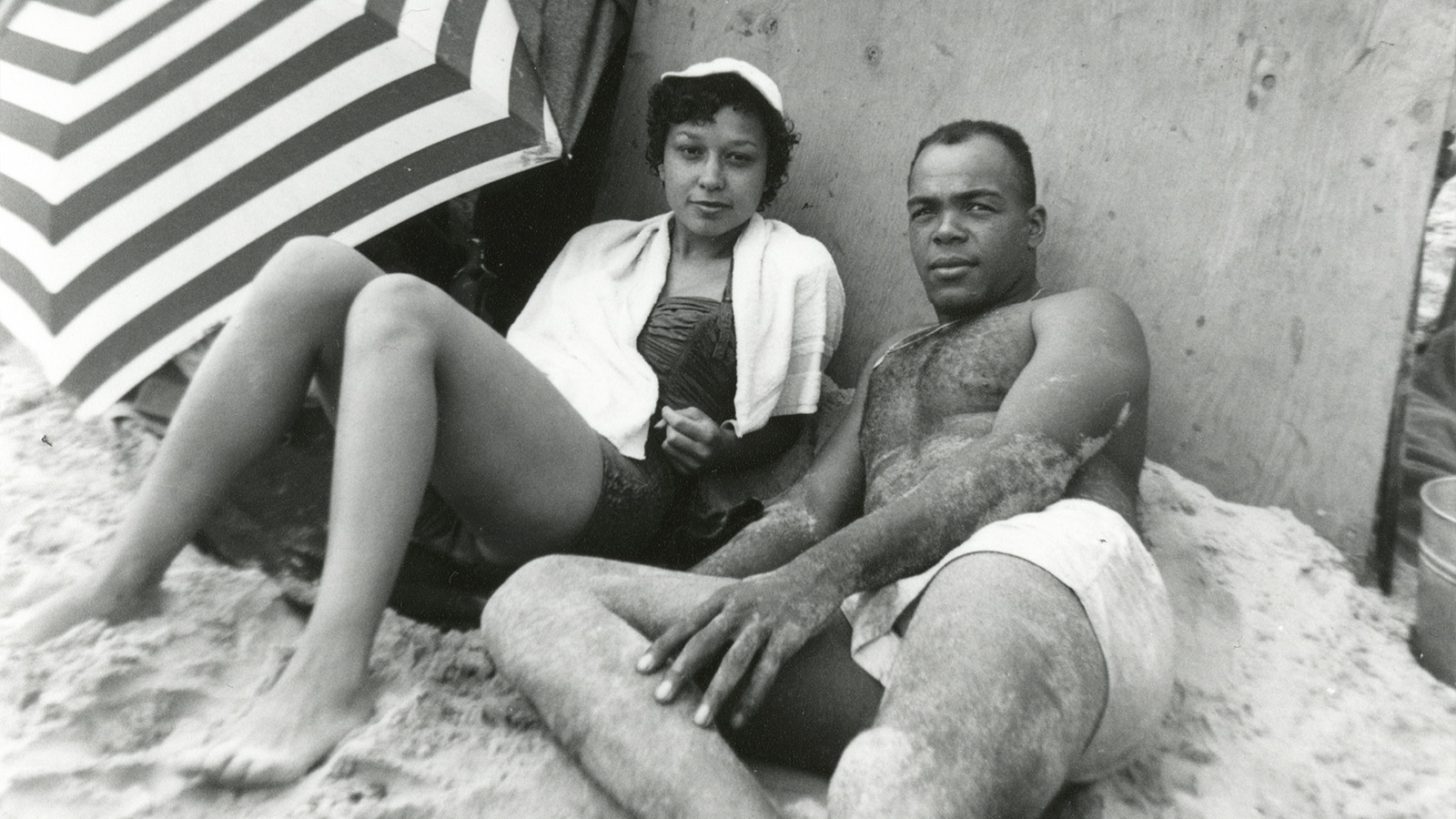

Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library, Duke UniversityA couple lounging on Bay Shore Beach, outside Hampton, Va. The property behind them is now a high-end subdivision. The beach is restricted to residents.

In 1910, less than 50 years after Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, African Americans owned over 15 million acres in the former slave-holding states. Much of that black-owned property was on the coasts, the geographic margins of the nation, which at the time were some of the most undesirable areas for living or leisure.

That was before the Army Corps of Engineers came along to convert those coastline areas into “flood protection” zones, and beaches. The Corps dumped over 7 million cubic yards of sand in Mississippi to create “the longest manmade beach in the world,” but not for all to enjoy. When the federal government brought the sand to the beach, and a highway system for city folk to access it, in came droves of white folks, who then effectively drove black landowners out of their homes.

What the lauded black scholar W. E. B. Dubois called “the color problem of summer,” the National Park Service called the “spectacular acceleration [of] private and commercial development” of America’s coasts. What DuBois was referencing, and what the Park Service was ignoring, was the violent pushing out of former black landowners into segregated, polluted nooks of the shoreline, if not off the land altogether.

Harvard University PressAndrew Kahrl.

University of Virginia history professor Andrew Kahrl calls it “coastal capitalism” in his book The Land Was Ours: African American Beaches from Jim Crow to the Sunbelt South, released somewhat quietly in late 2012. If you’ve been following my blog, you’ll note that I’ve referenced the book a couple of times, including in my last post on how black people have been historically excluded from safe swimming spaces in the U.S.

Kahrl not only details the deleterious impacts of racial segregation in his book, but also how the white overthrow of black landholdings — from Maryland shores to Texas — was closely linked to the pursuit of reckless environmental policies in the name of profits. Many of the same properties stolen from African Americans are today threatened by climate-change-fueled sea-level rise and coastal erosion.

Writes Kahrl:

The shores that African Americans steadily lost over the course of the second half of the twentieth century … demonstrate the inextricability of environmental and human exploitation — power over lands and power over persons — and force us to reassess the familiar story of America’s triumph over segregation, its achievement of civil rights, and its slow, painful but nevertheless inexorable progress toward a more just and equitable future.

I caught up with Kahrl by phone to further unpack his research around racial segregation, “coastal capitalism,” and how these might be reconciled under the wrath of climate change.

Q. The stories in your book are mostly about social “soft” sciences like race discrimination, but you write quite a bit about problems like coastal erosion and climate change. Did you anticipate exploring those harder sciences going in?

A. That wasn’t initially part of the story, but it became an essential feature of that history the more I worked on it. I ended up trying to rethink or at least expand the way we understand environmental racism. We often think of it strictly as cases of African Americans being disproportionately affected by the damage done to the environment, from the siting of polluting industries or what have you. But here we have cases where whites are doing damage to their own environment while in the process of carrying out racist policies.

African Americans are victims of being pushed off the land, and at the same time those same policies are destroying land itself, and sometimes those two worked hand-in-hand. Like in New Hanover County, N.C., where you had the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers carrying out policies that are literally eroding the foundation of black coastal landowners, which then ensured that it would be very difficult to continue to sustain a livelihood there and results in their eventual displacement.

Q. And this continues today, right?

Q. And this continues today, right?

A. We have, over the last half-century, this steady process of restricting public access to beach areas in the Northeast. A lot of it is driven by fears of the civil rights movement spilling over into what had previously been white enclaves. You started to see this push towards restricting public access to beaches oftentimes out of an ostensibly race-neutral policy like resident-only policies or even by building physical barriers that restrict the public’s ability to access areas that had long been upper-class white coastal communities. Well, in the process of trying to armor themselves against the prospect of hordes of urban masses flocking to their shores, they were also destroying the very environment that they were seeking to protect.

Q. Maybe this is unfair, but given what climate change is poised to do to these coastal communities I couldn’t help but read a certain sense of karma in these stories.

A. It would be poetic justice if it only affected those persons carrying this [racism] out, but instead it affects all of us, because it’s our planet. It also affects us in other ways, like by shifting our priorities as a country, it’s shifting tax dollars toward the rebuilding of playgrounds for the rich, and just having a really corrosive effect on the body politic as a whole. It absolutely reveals the multifaceted damage that racism does to us as a society and to the planet.

Q. Ta-Nehisi Coates’ recent Atlantic article laying out a case for reparations for African Americans is told through the lens of a working-class black family from really humble beginnings. But your book centers a lot on stories of African Americans who actually had some measures of wealth and land ownership, only to have it stolen from them. Do you think your book bolsters the case for reparations for African Americans?

A. Well, I think we need to shift the focus from cash payments to people of color, which is the stereotypical argument of what reparations constitutes, and more toward structural reforms that will address and eliminate the sort of instruments of racism that have been carried out for generations and continue to operate and are really in many ways intrinsic to our system of capitalism — and that’s a conversation that most Americans don’t want to have.

With regards to these characters (in the book), these are folks whose wealth was never realized. The one thing about the African American experience under Jim Crow, when talking about wealth and the inability to accumulate wealth, the landowners who I discuss, these are folks who emerged out of a century of Jim Crow with one asset, which was land. They never got a chance to realize that wealth. Those lands instead became a source of wealth for others.

The perfect example is Hilton Head, S.C. That land was once owned by African Americans, but is now worth hundreds of millions of dollars and the [black] people who [previously] owned it never got a cent. It’s the same thing we’re seeing today in these gentrifying neighborhoods where the land is highly valuable, but the people who lived on it didn’t get a chance to enjoy the riches that came from it. Coates uses the word “kleptocracy” to describe this and it’s very powerful and very accurate in the sense that the state is operating in ways to facilitate the dispossession of African American assets.

Q. So given all of this, do you see a way for the nation to reconcile its debt to African Americans while also reconciling a sustainable future under climate change’s threats?

A. It’s hard to imagine when you have states like North Carolina, which just passed a law that forbids coastal engineers and state agencies from even acknowledging the existence of climate change. But yeah, it’s a tricky issue of how do we begin to right these past wrongs in ways that are actually meaningful for people who actually suffered that damage and their descendents — the people who are living in trailer homes while the land that their parents owned has now been turned into golf courses and multimillion dollar mansions. There’s no real easy answer that doesn’t involve a transfer of assets and wealth in a way that does compensate those people who had their land stolen from them by legal means.

Going forward, if there is a realization that [the current] model of development in these areas is unsustainable, then one of the ways to address this is to look back to previous models of living here, when [African Americans] were much more in tune with living in volatile environments, and ones that are much more well adapted to living in an age of rising sea level.

So, for instance, I was out in the Sea Islands [off the coast of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida] in April, and you drive through these areas like John’s Island, Wadlamaw and Kiawah Island, these are areas that used to have large numbers of independent, self-sufficient black farm families. Today, the African Americans are still living on these islands but in these Habitat for Humanity villages. They have no means for actually living off the land, they have no place in the island economy other than as low-wage service workers. Their very way of life was destroyed.

At the same time the islands themselves are being destroyed in ways that will really become apparent in the future. So what do we do for these people who are living in these trailer homes, where their ancestors were living as proud independent farming families? One way is to look at those older models of living — not that return to the Earth in any kind of nostalgic way — but begin to recognize how we can adopt a new model. So learning from the past and also compensating for past injustices, and finding a way that those two can be brought together.