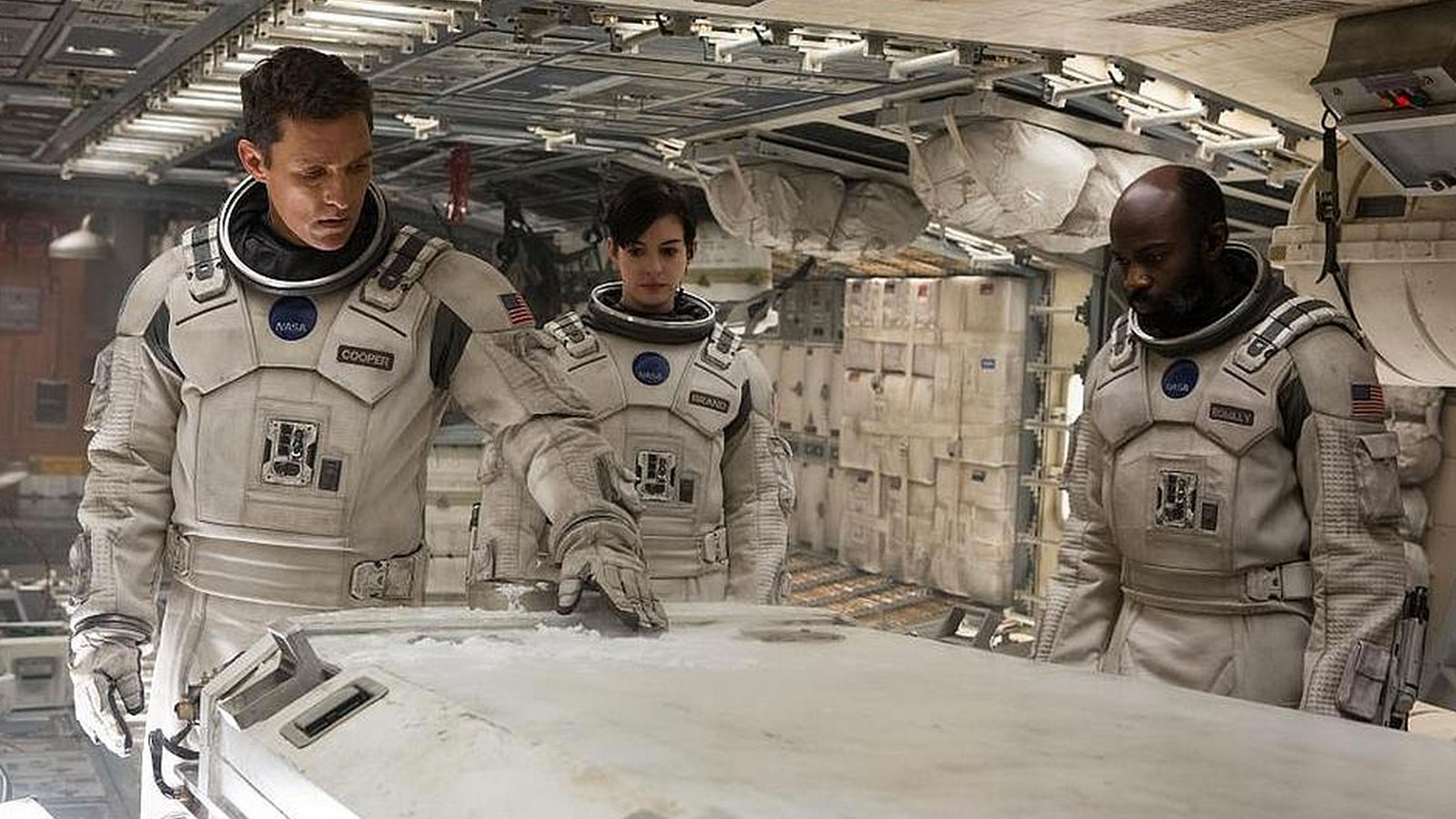

Welcome back to Green Screen, where Grist writers put on their proverbial cinephile hats to talk about movies, television, video games, and any heretofore undiscovered media on two-dimensional surfaces. This week, a star team of Gristers turn their sights on Christopher Nolan’s new movie, Interstellar, which opened in theatres this week.

The basics: In the near-ish future, thanks to humankind’s excess, the Earth becomes a waste of Dust Bowl-era desolation, with multiplying crop blights that apparently threaten to outcompete humans for atmosphere to breathe. Obviously, the only thing to do is to take a spaceship through a wormhole in search of habitable planets in other galaxies. Obviously.

Why it’s green: When it comes to spectacle, climate change can leave a lot to be desired (Al Gore giving a powerpoint? Polar bears looking vaguely disgruntled? Ice melting?). That’s why we were SO PUMPED to see the ringleader of spectacle, Christopher Nolan himself, take on a version of anthropogenic climate change as supervillain of his newest, splashiest, most space-tastic film yet.

Well, climate change and also the uncompromising absolutes of space and time. And admittedly, there is much more spectacle to be had from the latter, whether from glorious mind- and time-bending singularities to epic surfing of massive alien waves, while back on Earth all we get are some flaming corn fields and a few ominously looming dust storms. Nice and doom-y, but everyone knows that’s not really what you’re here to see.

Warner Bros. and Paramount Pictures

Eve: I walked into this movie thinking: Alright, if Matthew McConaughey is going to be playing a LITERAL ROCKET SCIENTIST who talks about climate change and is a sensitive father and says everything in the kind of Texas accent that should have melted the ice of one of the godforsaken planets he landed on, I am just going to be enthralled from the get-go. Game over. This movie was made for me.

I was wrong.

First of all, I can’t recall a single semi-coherent statement that Rust Cohle: Space Edition made about climate change throughout the movie. “There sure is a lot of dirt flying around this fucked-up ol’ planet!” pretty much sums it up.

Second of all, I found the decision to base a driving part of the plot on this dude’s blind commitment to return to his family pretty inexplicable given the fact that it takes him about 47 seconds to decide to leave them to go on a shockingly ambiguous, probably fatal space mission. “THEY CHOSE ME!!!” says Ben Barry, post-quantum physics Ph.D. “I HAVE NO CHOICE!! I MUST LEAVE THIS MORNING!!!” “But Dad –” “NO TIME!!!!! GOOD BYE!! HERE’S AN OLD WATCH THAT WILL LATER HAVE EXTREME BUT INEXPLICABLE SIGNIFICANCE.”

Third of all — I would still listen to Matthew McConaughey read a phone book. The accent was perfect. It always is.

Amelia: I think that might take about as long as actually watching this movie did. And have about as much to do with climate change.

Nathan: I never got the sense that the movie’s big bad was climate change. I though it was “the blight” — however it came to be — which systematically killed nearly all plant life (or at least food plants ). So the global threat of human extinction is from total ecosystem collapse, not climate change. I didn’t go in expecting that, nor feel like it was raised by the movie itself. The cause of the blight goes unmentioned and its consequences are presented as brute fact — not something the characters are here to explain or solve. The dust clouds aren’t the puzzle to solve, but rather the drum beat to extinction that gives urgency to the character’s choices.

Sam: We should say that the dust-storming Earth-pocalypse that goads humanity into wormhole-connected galaxies in search of other habitable worlds is not explicitly the global warming that threatens our species in real life.

As a card-carrying degrowther, I was really digging the first few minutes of the movie, when everyone was focused on fixing Earth by living modestly, not looking to jump ship for another planet to destroy. But I guess the script never even really stated that the environmental catastrophe the characters face is human-caused. In fact, Matt McCo even sat on the porch at one point and Texas-drawled that the Earth didn’t want people to live on her no more. Sounds like the typical Republican description of natural climate change.

Eve: Sam … it seems like you would have hated every minute of the movie after the first three, if this is true. Since there were approximately infinity more minutes, I really apologize for that whole evening.

Warner Bros. and Paramount Pictures

Amelia: Speaking of infinity, I want to say that I had high hopes for the science in this movie. I mean, Kip Thorne designing your black hole: SWOON. However, like many a high hope, these ones ended up Icarus-diving into a sea of incoherence and gravity mumbo-jumbo pretty quickly.

Sam: Really? I heard that unlike Gravity, Interstellar supposedly obeys physics, but I don’t know enough to test that.

Eve: Did Gravity not obey the laws of physics? I guess I have to send back my IB Diploma; I bought every second of it. I bought about four seconds of Interstellar.

Ted: Four seconds of cred is still more than is present in the entire Transformers quadrilogy. I think at the end of the day, Gravity and Interstellar probably come about even on scientific accuracy. Sure, NDGT complained on Twitter about Gravity’s astrophysical lapses, but a lot of other astronomers were quick to jump on and explain what they did do right. I bet we’ll see the same thing for Interstellar. At minimum, I’m pretty sure existing at the center of a black-hole library and nudging a watch with your mind-gravity to blurt out “quantum space data” into Papa’s watch stretches Kip Thorne’s scientific consultancy a hair. Oh, wait, there was an explanation: “They.”*

*Spoiler: They is us. Did I just blow the movie and all acceptable grammar simultaneously? Blame singularity.

Amelia: But that’s actually not the worst part! If your space odyssey takes you to an infinite Borgesian library of spacetime every once in a while — fine! It happens to the best of us and I can go with the flow. Where this movie lost credibility for me was not the science, but the scientists.

Yes, we all know that scientists are people, too, but movies like this use scientist characters as grumpy mouthpieces for the most-feelingsy chunks of script. Take, for example, one of two token lady-scientists, played by Anne Hathaway, who spent most of her time imitating a joyless robot only to get to utter the perplexing idea that “maybe love is an artifact of higher dimensions.” Huh. What do those words even mean? I sure don’t know — and yet, because they came out of the mouth of sanctioned Science Person, I think they’re meant to hit us as qualified truth.

If we are a society that thinks of science as a kind of magic whose main method can be distilled down to “follow your heart” then no wonder we’re getting in trouble with the basic facts of global warming here at home.

Warner Bros. and Paramount Pictures

Ted: Let’s talk for a hot second about everyone’s favorite dilation … TIME! (sorry, midwives and optometrists). Here’s one thing I think Chris Nolan got right. Dramatizing clear-and-present dangers that elapse over massively long time scales — climate change, space catastrophes, peeing your pants during Interstellar’s infinite running time — remains a persistent challenge for storytellers, especially in film. By situating the action near black holes, Nolan was able to make 23 years of horrible climate effects feel urgent. Casey Affleck’s family keeps dying of dust lung over long decades, while Space Cowboy Coop tries to shred the raddest big wave ever. If he pulls it off, bang! New home found, climate crisis over.

Amelia: That may actually be the best possible reason to make a movie co-featuring intergalactic space travel and climate change. If we had to watch this whole saga as a series of real-time policy quibbles, terrible election cycles, and scary but remote natural disasters — well no wonder TV news is so bad.

Warner Bros. and Paramount Pictures

Eve: A bit about love: I’m enough of a romantic that I’ve seen How to Lose A Guy in 10 Days at least five times and cried at least 60 percent of those times, and even I could not roll my eyes far back enough in my head at the claim that love transcends dimensions. I’m sorry — no. Love can stretch over time and space, but it doesn’t keep you from abandoning your kids to go on a suicide space exploration mission that you found out about two hours ago?

Ted: It’s far from perfect, but the love thing goes some measure to address one of the Big Questions these characters are always blurting out like overconfident sophomore philosophy majors on some grassy quad: How can we think like a species instead of a bunch of tribes to address our biggest problems?

I guess the answer (yes, spoilers) is either an inelegant, “we can’t; let’s sensitively kill each other on a glacier, but don’t be mad bro,” or the even more milquetoast “love.” I guess as far as cop-outs go, though, love is pretty infallible and conquers all — time, gravity, myriad space holes. Sorry, Eve.

Nathan: I thought we are meant to take Hathaway’s line, “what if love is an artifact of higher dimension” with skepticism — that the rational choice is being made against her bias, as there is no evidence to support what sounds like a meaningless proposition to begin with (at least to a logical positivist). The irony is not that her choice of planet happened to be the right one, but that in the tesseract, it was an act of love from a higher dimension (by the very person who doubted the possibility).

Ted: Well, Nathan, you are clearly the Philosopher King among us.

Warner Bros. and Paramount Pictures

Amelia: Let’s end at the beginning, with what I think is the biggest question of this movie: Do we really believe this whole space-gambit was warranted in the first place? OK, yes, we screwed up the Earth, but wouldn’t it have been easier to commit those billions and billions of secret NASA dollars toward eradicating blight and adapting new crops than sending THREE PEOPLE to recon another galaxy? Or at least take the middle road and build that fancy space colony next to Saturn, and skip the whole can of wormholes altogether?

Eve: Amelia. They clearly had to solve gravity before they could figure out how to build the space colony!!

Amelia: Did they, though? Did they really need that?

Ted: “Solving gravity” is going to be my new excuse for being late, like, every time. I also thought it was strange that the “let’s become mole people underground!” or “let’s live at the bottom of the sea!” option wasn’t ever explored. Well, not so strange: I guess we need every plot device possible to just get Galactic Dallas and Cosmic Cosette into those eye-popping special effects.

I do love the idea of restoring NASA to its former (and even greater) glory, but Interstellar automatically assumes we’re gonna blow this whole adaptation thing pretty badly.

Amelia: Here’s the quote I’m stuck on: “The world doesn’t need any more engineers. We didn’t run out of planes and television sets. We ran out of food.” That seems like a pretty blanket dismissal of a whole stable of problem-solving tools based on a few questionable applications — like, maybe stop trying to build a better flatscreen and focus on how to use technology to solve the (literally) existential problems of the human race. I can’t believe that intergalactic space travel was the best route to food security; neither is dismissing science to soldier on blindly through the dust-pocalypse.

Eve: And also, apparently, they ran out of much more important things than planes and television sets — i.e., MRI machines [see: the late Mrs. Cooper]. So, engineers may have come in handy after all!

Ted: Since we spent a whole lot of time irradiating Interstellar with quantum shade, I think it’s important to note that I enjoyed the sensory experience. I basically don’t have to visit Saturn now — crossing that one off the bucket list.

And yeah, the experience falters when you scrape the thin paintjob of logic to find a motherlode of stupid underneath. But let’s be fair: All the holes — worm, black, plot — were pretty spectacular.