Theodore Roosevelt had his delicate spots—he was an asthmatic child and later a naturalist who reveled in birdwatching. But 100 years after his presidency, the image of him that endures is decidedly more swaggering—an outdoorsman who loved to hunt, a mountaineer, a populist who thundered against corporate “despoilers” of the public welfare.

Theodore Roosevelt had his delicate spots—he was an asthmatic child and later a naturalist who reveled in birdwatching. But 100 years after his presidency, the image of him that endures is decidedly more swaggering—an outdoorsman who loved to hunt, a mountaineer, a populist who thundered against corporate “despoilers” of the public welfare.

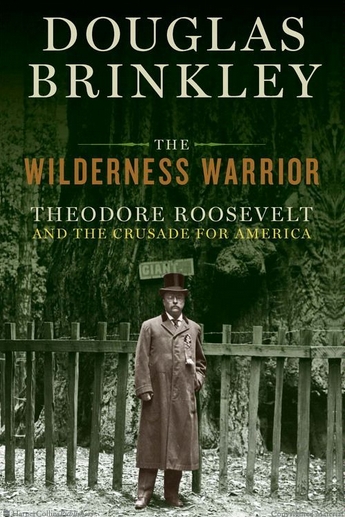

He also left a legacy of 234 million acres of national parks and other protected American wilderness. Historian Douglas Brinkley, who has written acclaimed books on Ford Motor Company and Hurricane Katrina, focuses on the conservationist work of the larger-than-life president in his new book, the 960-page Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America.

We spoke recently about Roosevelt and how he might have taken on today’s despoilers.

Q. Roosevelt’s time in the Badlands, on his African safari, and in the mountains with John Muir—he seemed link it all to his work in public. What was it that he found in the wilderness that made him such a powerful leader?

A. He had chronic asthma as a boy and got very skeptical about hyper-industrialization, seeing the smokestack factories along the East River in New Jersey. Yet when he’d go to the Catskills and later the Adirondacks, his illness would go away. He found that being out in the wild was the cure to his respiratory illness.

He also created a philosophy that what made American democracy unique was wilderness. He believed that it would have medium-sized cities surrounded by what we today would call greenbelts. And that if you let sprawl happen it would desecrate the beautiful American landscape.

He was also very influenced by the writings of Charles Darwin and this notion of the need for species survival and the classification of species. Roosevelt’s greatest accomplishment may have been his leadership in inventorying the biotic America. He wanted to know what kind of wildflowers we had, what insects, what types of prairie grass. And he wanted to educate people that the planet was one whole thing, one biological organism.

Q. What would he think of the so-called unscientific America today, where so many people reject evolution?

A. He would be aghast at people ignoring science. He pushed for science and biology to be taught in public schools. He wanted all children to grow up understanding Darwin and Huxley. On the other hand he was a bit of a romantic about nature. The combination of the two made him almost an ideal president for the current environmental moment.

Q. Today we’ve got big business interests—the National Association of Manufacturers for one—saying the world is going to end if we pass a climate change bill. It sounds like Roosevelt faced the same kind of opposition when he took on the mining industry and others who didn’t want places like Grand Canyon to be protected. What was his strategy?

A. He would have taken his fist and smashed the National Manufacturing Association. I’m not kidding, he was that vigorous a figure. Anybody who put a company profit over the public welfare, Roosevelt called them despoilers. It was his favorite word. He also called them swine. It was a trend of capitalism he worried about, that we would create a culture where the corporations could do what they wanted for their profits and do damage to the public welfare.

Q. Do we have anyone of any influence speaking like that today?

No, we don’t. Roosevelt cloaked himself in American mythology–he’d wear a cowboy hat and bandana, carry a gun, and present himself as kind of an archetype of American manhood — so he could talk to common people. Sometimes 200,000 people would come to hear him give conservation speeches.

He didn’t see it as negotiable. He was a pragmatist, but there were some things that you couldn’t negotiate. You couldn’t partially mine the Grand Canyon. It needed to be preserved forever. And that was the end of the conversation. Even though Congress voted to mine it for zinc and asbestos, Roosevelt used an executive order and overruled them.

Roosevelt also called for a global conservation congress that would have global environmental laws. One hundred years ago, in 1909, he called for that. He knew that it doesn’t go any good to save birds in America if they go down to Central America and the whole flock is massacred. It doesn’t do any good for us to keep the Rio Grande clean if Mexico’s going to dump sewage in it. So Roosevelt’s notion that we could work in a global fashion on conservation issues is very timely today.

Q. Did he have any success with that?

A. No. The first one he passed was with Canada and Mexico, and it was successful. But they were planning the global one when he left office and went to Africa to collect for the Smithsonian Institute. William Howard Taft came in with the Republican big business crowd, and they threw out the idea.

Q. A politician going to the wilderness for self-reflection–that’s such an exotic idea today, Appalachian Trail jokes notwithstanding. What’s lost with that?

A. Well, it’s tough to do. I think it’s good that President Obama visited Yellowstone and the Grand Canyon last weekend. But I’d also like the president to get into some of the wilderness areas of America and to start thinking of immediate things that can be done on climate.

For example, ANWR in Alaska should become a national monument or park. Obama should create a national caribou reserve. Roosevelt created national buffalo reserves—the Wichita Mountains in Oklahoma and at the Flathead Reservation in Montana–wildly successful efforts to keep the buffalo alive and thriving. We need to do that now for the caribou that climate change has put under great stress in Alaska.

Historian Douglas BrinkleyPhoto: Danny Turner for HarperCollinsQ. And Obama could do that through executive order?

Historian Douglas BrinkleyPhoto: Danny Turner for HarperCollinsQ. And Obama could do that through executive order?

A. He can. He could do it tomorrow with an executive order declaring ANWR a national monument. The only problem is a weird stipulation put on ANWR in 1980 that says it would be sacrosanct for only one year, and then Congress would have to agree to it. He would have to use the political muscle to get votes on Capitol Hill. But he could get them. It’s just a matter of wanting to have these fights. [Update: See below for more on conservation law in Alaska.]

And on the Mexican border, wildlife is dying like crazy because they’re building a wall that’s killing off an entire wildlife corridor. The wall is idiotic. There’s a lot that can be done besides the big difficulty of weaning the world off of its addiction to petroleum. Those are proactive things the Obama administration should be doing now.

Q. Do you see any way that the Republican Party might embrace his conservation legacy and reclaim the environmental heroes in its past?

A. We’re on the verge of a new green revolution, and I think I think there’s an opportunity for the Republican Party to reinvent itself as promoting it. The problem is the oil lobby and the coal lobby are so powerful in Republican politics that nobody wants to stand up to them. Until you get a Republican of great vision who can be Rooseveltian in putting long-term public welfare over short-term corporate good, I don’t see it coming any time soon.

Q. How do we make environmentalism badass again, the way it was for Roosevelt?

A. Everybody likes TR, because we can see that his legacy is not a Democratic legacy or a Republican one, it’s a great American legacy. I don’t think we have to be at partisan odds over clean air, clean water, and keeping our forest reserves intact. Those should just be American goals. And I think Roosevelt helps that process along.

There’s always a need for an alliance between sportsmen–hunters and anglers–and the preservationists in the environmental movement. They have different interests, but when they work together they can get a lot of things done. It can often mean those extra Congressional votes. I know for a fact that these hunt clubs, many of them for their own reasons, want to have caribou and polar bears saved in Alaska right now. Green activists might be able to form alliances with them, working against the extraction industries. Roosevelt provides an example of bringing those communities together in a common, concerted effort.

Watch Brinkley talk Roosevelt and Wilderness Warriors on the Daily Show with Jon Stewart last week:

[vodpod id=Video.16072662&w=425&h=350&fv=autoPlay%3Dfalse]

Update: More from on Arctic National Wildlife Refuge conservation law from Cindy Shogan, executive directory of the Alaska Wilderness League (AWL):

The short answer is that ANILCA (Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act – passed in 1980) says that large withdrawals of public lands terminates unless Congress extends the withdrawal through legislation within one year of the withdrawal.

Yes, an Arctic Monument would be large – but we would argue that this is not a new withdrawal, these lands are already withdrawn.

Shogan also directed me to attorney Peter Van Tuyn, who has done work for AWL. He provided this anwer:

With passage of ANILCA in 1980, Congress purported to “provide[] sufficient protection for the national interest in the scenic, natural, cultural and environmental values on the public lands in Alaska.” ANILCA § 101(d), 16 U.S.C. § 3101(d). Among other provisions, the Act set aside more than 104 million acres in new and expanded “conservation system units” and created 56.4 million acres of wilderness. In doing so, Congress stated that ANILCA struck the proper balance between lands set aside for conservation and lands left available for other uses, and as such, future legislation creating new conservation system units in Alaska would be unnecessary. Id. Based on this balance, ANILCA’s so-called “no more” clause limits future actions by the executive branch to establish or expand conservation system units in Alaska. ANILCA 1326, 16 U.S.C. § 3213. The provision renders ineffective any executive withdrawal of land that exceeds 5,000 acres in the aggregate absent public and congressional notice and a joint resolution that approves the executive action. If Congress, within one year, does not ratify the executive land withdrawal it automatically terminates.

Layering an Arctic Refuge Monument over the existing Arctic Refuge does not, by itself, violate the “no more” clause. As noted above, ANILCA’s “no more” clause limits the authority of the executive branch to withdraw public lands in excess of 5,000 acres without the express permission of Congress. 16 U.S.C. § 3213(a). The language of the “no more” clause, however, clearly indicates that the provision is only triggered when a withdrawal of land actually occurs. The general understanding of the term “withdrawal” in the public lands context means a removal of land from the operation of some or all of the public land laws under which the land would ordinarily be made available for settlement, mineral location, or other forms of disposition or private use. Currently all land within the Arctic Refuge, in particular the coastal plain area and wilderness areas, are fully withdrawn from operation of the public land laws. As a result, in its existing state, the land in the Arctic Refuge cannot be further withdrawn, and establishing an Arctic Refuge Monument would thus not run afoul of the “no more” clause.

As with anything legal, there are other nuances to the answer, but this is the gist of it.