Jeff Goodell.To head off the worst impacts of climate change, should human beings deliberately engineer the earth’s climate? Or rather, should they try, with uncertain odds of success and at least some chance of inadvertent catastrophe? Should they even learn how, or would the knowledge itself wreak havoc?

Jeff Goodell.To head off the worst impacts of climate change, should human beings deliberately engineer the earth’s climate? Or rather, should they try, with uncertain odds of success and at least some chance of inadvertent catastrophe? Should they even learn how, or would the knowledge itself wreak havoc?

These are the sorts of questions journalist Jeff Goodell grapples with in How to Cool the Planet: Geoengineering and the Audacious Quest to Fix Earth’s Climate, due out on April 15. As readers of his previous book Big Coal know, Goodell’s talent lies in addressing heavy economic and political issues through the prism of individual human narratives. Once again he’s gathered a cast of eccentric characters and darkly entertaining stories that carry the reader through choppy conceptual waters.

Goodell and I discussed the promise and perils of geoengineering in wide-ranging conversation earlier this month. Here are some highlights, followed by more in-depth excerpts from our conversation.

On geoengineering of the crazier sort:

This is field of wacky ideas. I talked to a guy who thought it would be great to spread Special K out in the ocean to reflect sunlight and cool the earth’s temperature. People who want to launch nuclear bombs at the moon, to shoot moon dust into the outer space to reflect sunlight away.

On the two serious forms of geoengineering:

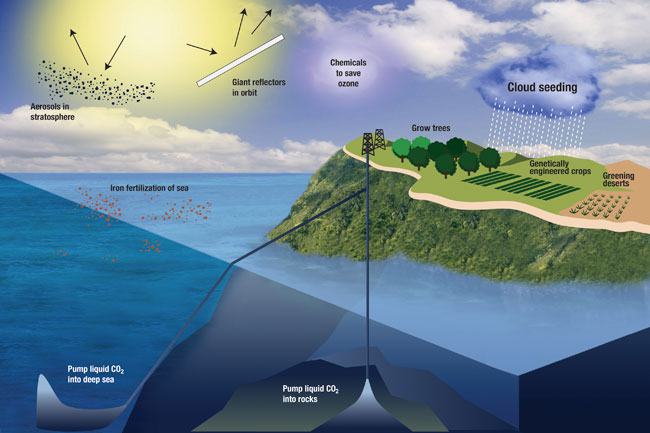

“Solar radiation management” or “solar shielding.” It’s about blocking sunlight. In order to offset the temperature change from a doubling of CO2 emissions, you only have to reflect a small amount of sunlight away from the earth — one or two percent. The other category is carbon dioxide removal — machines and technologies that can pull CO2 out of the atmosphere. These are far less problematic, politically and morally.

On environmental groups’ concerns about geoengineering:

It’s not so much the fear that we’re going to screw this up, though that’s part of it, but more the fear that we’re still trying to get a cap on CO2 and this is just seen as a kind of a political nightmare. It becomes an alternative, a quick fix, an easy sell. Why do we have to go through all the pain and hassle of political coalitions to cut emissions if we can just spray some particles in the atmosphere?

On whether knowledge about geoengineering should be restricted:

On whether knowledge about geoengineering should be restricted:

I went to Pompeii once a few years ago. They had all the porn in a separate room at the museum. It used to be that only men could go in there. It was seen as dangerous for women to go look at giant phalluses, because they’d get corrupted morally. It’s a bad idea for geoengineering to be the equivalent of the Pompeii sex room.

On whether geoengineering can be humane:

[There’s] a kind of parallel between geoengineering and gardening. This is about learning to garden the planet. I was inspired to think about this because of my wife’s garden, seeing this partnership with nature she has in her garden. It leads to a beautiful thing. The hopeful side of me thinks geoengineering can be smaller, smarter. It can be modest, about regional stuff, experimenting, learning what works, what doesn’t work. Being humble about this, being open about this.

On his worse fears about geoengineering:

The idea that a nation or a group of nations will decide, for nationalistic or militaristic reasons, or a genuine belief that they can fix their problems, to do this. They will do it badly, and cause a lot of climate chaos. … You can imagine the island nations getting together and saying, “You guys have been fucking around for 30 years, and we don’t want to drown, so we’ve got a couple of billionaires that are helping us with some airplanes. We are going to do this.” … It’s going to get taken up by the guys who want to blow up New York City.

But my nightmare scenario is that we won’t do anything. It will just be decades more of apathy. We’ll block progress on research on geoengineering, we won’t reform our energy system, we will just continue with the status quo for another two or three decades. We’ll just ride straight ahead into climate chaos.

On reactions to his book:

I’m already getting people who are pissed off at me for writing this book. It’s going to be controversial.

Read more from the conversation with Jeff Goodell:

- On the different kinds of geoengineering

- On “taking control” of the climate

- On messing with nature and being transparent

- On techno-determinism and inevitability

- On keeping geoengineering from running amuck

On the different kinds of geoengineering

Q. Could you offer a rough taxonomy of types of geoengineering? Which of them should we be taking seriously?

A. One of the first things I found out was, this is field of wacky ideas. I talked to a guy who thought it would be great to spread Special K out in the ocean to reflect sunlight and cool the earth’s temperature. People who want to launch nuclear bombs at the moon, to shoot moon dust into the outer space to reflect sunlight away. I try to focus on the serious ones. There are two distinct kinds.

One is what the British Royal Society, which did a big report on this last year, termed “solar radiation management” or “solar shielding.” It’s about blocking sunlight. In order to offset the temperature change from a doubling of CO2 emissions, you only have to reflect a small amount of sunlight away from the earth — one or two percent.

Of the solar radiation management technologies that can do this, there are two that people are thinking about seriously. One is spraying particles into the stratosphere — sulphate particles, similar to what comes out of coal plants except without all the dirty metallic toxins, or in the future, particles specifically engineered out of inert metals. So acid rain, pollution, inhaling them … you’re not going to have snow drops of this stuff raining down on your house or anything like that. It could potentially change the color of the sky somewhat. It could have aesthetic effects. But we don’t know of any health effects yet.

Another way is brightening clouds, which turns out to be the organic, homegrown version of solar radiation management. You can throw seawater into certain marine clouds that would act as cloud condensation nuclei and make the droplets smaller. Smaller droplets have more surface area, so they make the cloud a brighter color and it reflects away more sunlight. It’s a little difficult to imagine cloud writing used for the whole earth, but you could use it in specific areas, the Arctic or Greenland.

The other category is carbon dioxide removal — machines and technologies that can pull CO2 out of the atmosphere. These are far less problematic, politically and morally. One of the scientists I write about in the book is David Keith at the University of Calgary, who is starting a company to build enormous machines that can suck CO2 out of the atmosphere the way CO2 is sucked out of the stack of a power plant. There are some advantages to this because you can locate these machines anywhere. They are very expensive now, but there’s a lot of potential.

There are other ways of sucking up CO2. The most well known to many people is dumping iron slurry into the ocean to stimulate plankton blooms. The plankton absorb carbon and then, in theory, sink down to the bottom of the ocean and sequester it. Many problems with that — we don’t know how much is actually sucked up and how much makes it to the bottom. Another technique is biochar, a way of burning charcoal and burying it in the soil to increase the uptake of carbon in the soil.

There are lots of other ideas, but these are the main things that I talk about in the book.

Q. I noticed you left out white roofs and other small-scale efforts.

A. White roofs are a great example of things we are already doing to change the reflectivity, or albedo, of the earth. They have other benefits, like lowering the temperature of the house and reducing air-conditioning costs, but even if you whitened every roof on the planet, it still wouldn’t have much effect.

On “taking control” of the climate

Q. Did your feelings about geoengineering change over the course of writing the book? Where did you come out?

A. They did change. My initial thought was that it was just a completely crazy idea, that we were nuts to consider it. It’s the reaction anybody has when you say we’re going to start messing with the climate. It seems like a very hubristic undertaking. That’s the easy way to think about it. But after meeting some of these scientists and thinking hard about this, I came to take the idea seriously. We’re not talking about the climate equivalent of putting a housing development in virgin redwood forests. We’re already messing with the planet in profound ways, and as Stewart Brand and others have said, we might as well get good at it. It’s not crazy that we could learn how to control the levers of this system better.

In a certain way, we’re already doing this. Even by setting climate targets — 350 parts per million, or 80 percent reductions by 2050, or whatever — we’re making implicit judgments about what kind of world we want to live in. One of the interesting things about geoengineering is that it makes that conversation explicit. That’s an important idea: we are in charge of the climate whether we like it or not. It’s not a question of do we want to try to take control — we’re already in control. We’re already fucking with this system in a profound way.

Q. There are two things run together there. It’s one thing to say we’re screwing with things in a profound way; it’s something else entirely to say we’re in control of that. Control seems to imply intentionality, knowledge, and the ability to undo what we’ve done. You can’t skip past that.

A. Right. I don’t mean that we’re in control of the outcomes, but after, what, 20, 30 years of understanding that we’re running profound risks of destabilizing the climate by continuing to dump CO2 into the atmosphere, we’re still doing it. We’re not cutting emissions at all. We’re not trying to manipulate the weather right now, but we are, by our disregard, exerting a kind of control. Not setting any limits — that’s a kind of decision.

One of the things I like about the geoengineering discussion, for all its risks and craziness, is that it does make this explicit. That’s a good conversation to have.

Q. Even before climate change, before the industrial age, the earth’s climate clearly advantaged some people over others; there were massive inequalities. If you accept that we are in control, don’t you problematize the notion that the pre-industrial climate has any kind of claim on us? Why should we think that’s the preferable climate?

A. Absolutely. That opens the door to all the political complexities. Where do we want to set the thermostat? If, on some crude measure, we have the ability to decide what kind of climate we want, how do we decide? Who makes the decision? In Copenhagen, the developing world and some of the island nations are holding the West accountable for this. You can see the tension escalating as we move into this new world.

What happens if we get into some sort of climate emergency — something really goes wrong, not necessarily in the United States, but in China or wherever — and people demand some kind of political action? What do we do? We’re not going mandate that everyone sell their SUVs. Not only does that not work for social reasons, but because of the inertia of the climate, reducing CO2 isn’t going to have much effect in the short-term.

There’s a lot of worry that someone, China or India or some combination of the developing world countries, would try some of this [geoengineering] stuff out of desperation. You can imagine the island nations getting together and saying, “You guys have been fucking around for 30 years, and we don’t want to drown, so we’ve got a couple of billionaires that are helping us with some airplanes. We are going to do this.” How would the West respond? How would anyone respond? There are all kinds of big implications, from the environmental part of it to the military and nation-state aspects. These kinds of things are percolating in the background because, while we don’t know that we can do it right, or do it without catastrophic consequences, we know that it’s doable.

Q. One of the fascinating things about this, especially in this early stage of things, is how much history is being shaped by this relatively small set of idiosyncratic personalities. Individual people can have a relatively huge effect on how it unfolds. I don’t know if that’s scary or not.

A. One of the reasons I wanted to focus on some of these scientists is that I was fascinated by this sort of hubris they must have to even be thinking about this kind of a thing. Do they have integrity? Are they nuts?

But that’s not where I came down. As you know from reading the book, the people I focus on, especially Ken Caldeira and David Keith, I came to deeply respect their reasons for doing this. That was encouraging. But there’s this worry that all these ethical scientists are working on it now, but as soon as it gets a little more perfected, it’s going to get taken up by the guys who want to blow up New York City. This will soon get taken out of their hands. I was struck, reading Oppenheimer’s biography, thinking about how he worked on this for what seemed like all the right reason, and then what happened so quickly to his dream. There are a lot of parallels.

On messing with nature and being transparent

Q. At times in the book you seem to characterize environmentalists as ideologically or almost religiously opposed to any mucking about with nature. I felt like they were almost being used as straw men at some points. Did you run across people like that, who categorically oppose intervention?

A. It’s hard to characterize. There’s not broad knowledge out there [about geoengineering], in general. But when I would talk about this with environmental groups, it’s not so much the fear that we’re going to screw this up, though that’s part of it, but more the fear that we’re still trying to get a cap on CO2 and this is just seen as a kind of a political nightmare. It becomes an alternative, a quick fix, an easy sell. Why do we have to go through all the pain and hassle of political coalitions to cut emissions if we can just spray some particles in the atmosphere?

Q. This is obviously an incredibly consequential question: What effect will the knowledge itself have? Will knowledge of how to undertake geoengineering sap the will for carbon cuts?

A. Let me say two things about that. One, it’s not like there’s a tremendous amount of momentum and progress to derail. It looks to me like business as usual as far as the eye can see. And second, it may be that geoengineering plays the role of the sort of drunken crash film they show you in drivers ed. Like, oh fuck, this is the sort of thing we don’t want to do! If we don’t get our act together, we’re heading for this freako world of geoengineers and climate control! Nobody knows how this will play out. That’s one reason we need real research.

I went to Pompeii once a few years ago. They had all the porn in a separate room at the museum. It used to be that only men could go in there. It was seen as dangerous for women to go look at giant phalluses, because they’d get corrupted morally.

It’s a bad idea for geoengineering to be the equivalent of the Pompeii sex room.

Q. There’s my headline. I would like to think it’s going to serve the crash-film role. The geoengineers themselves, [Carnegie Institution atmospheric scientist] Ken Caldeira and those guys, say explicitly this is a back-up plan, that it would be a bad thing if we were forced into a corner and had to use it. They are saying the right things. But to the extent it leaks out into popular media, you get the SuperFreakonomics guys saying, “Oh, I guess Al Gore’s a big dummy.” When it hits pop culture it loses the nuance, the sense of caution. I cringe to imagine the story Politico would write about this, you know? How do you keep the cautionary note attached?

A. I have to say, that was my biggest concern about doing the book. Do I want to be part of that? I’m already getting people who are pissed off at me for writing it. It’s going to be controversial. It came down to the fact that I don’t believe in secrecy. I don’t think you can control these ideas. We learned from the way science operated during the Cold War that we want openness, we want transparency. We don’t want this as some black ops project. There is a kind of inevitability about this, so we may as well start having a frank talk about it. I think it’s good that I can talk about it in the context of the dangers, help try to frame this in a relatively balanced and intelligent way.

On techno-determinism and inevitability

Q. Let’s talk about that. Lots of people in the book expressed some version of that thought: we know this stuff, we have these tools, and therefore it’s inevitable we will use them. How certain are you about this techno-determinist view of things?

A. Well, I’m not sure about anything that’s going to happen in the future. But if you look at this very broadly, altering our environment is what humans do. Have you ever been to Houston?

We’re forced into that direction with climate because of what we’ve done so far and the risks of catastrophic change. It’s interesting, when you talk to people like Ken Caldeira — he’s anything but a technological cheerleader. He helped organize the big anti-nuke rallies in Central Park. But his work has shown that a geoengineered world may be more like our world than a non-geoengineered world.

We all know weather is chaotic. We can’t predict what’s going to happen next week, so how are we going to predict what’s going to happen in the next ten years? But when you talk to these guys about the possibility of climate control broadly, they don’t see it as that complicated of a project. The levers and pulleys in this system are not as complex as you would think. That doesn’t mean that we are going to be able to target rainfall over Iowa or something, but this is not as scientifically complex an idea as it would first seem.

It’s also important to remember, you and I are talking about this from a U.S. point of view. The ghost of John Muir lingers in all our conversations. But look at what happened in China on the 60th anniversary of the Communist Party. They were promising blue skies, shooting all of this stuff into the sky to get rid of the clouds. No one knows that this cloud seeding stuff works; it’s all a level of hocus pocus. But they were doing it on a massive level, with dozens of military jets, simply for the political symbolism for it. There are no Muir-esque taboos about messing with nature in a culture like that.

On keeping geoengineering from running amuck

Q. What do you see as the route to getting some sort of international legal structure in place to govern this stuff? Do you see any precedent?

A. There’s really not one. The policy part of this is difficult and complicated. Obviously there’s some comparison to nuclear proliferation, in that you have to ask, how do you restrain a lone actor? It’s striking to me that a lot of people with expertise in nuclear arms and negotiations are beginning to get interested in geoengineering.

One of the things [Stanford law professor] David Victor talks about in my book is the danger of setting policy too early, before we know what the real issues are and what the science tells us. To start imagining governance structures right now is important on some high level, but what’s really important is finding out what the risks are, what works and what doesn’t, which engineering challenges are going to be surmountable and which are not. We still haven’t actually sprayed particles into the atmosphere! So in the near term, the big regulatory and governance challenge is how to set up field experiments. Modeling and conferences only take you so far. At a certain point we need to try some of this stuff.

Q. It was a bit of a surprise to me to read that it would take about ten years to set up a high-quality, controlled experiment with solar shielding. Ten years isn’t long in climate terms, but sociopolitically, ten years is ages. It seems we’ll be in the dark about this for quite a while.

A. That’s how long it will take to set up a large-scale field experiment. And that is a long time. It suggests the importance of starting to think about it now. Also, there’s a lot of other work that can be done prior to that — engineering the sprayers and things like that, work that can be done on a smaller scale. There’s lots more modeling work.

This is ten years to do a top-notch scientific experiment on a large scale. It doesn’t mean somebody can’t go up there and just start doing this, and doing this badly. It doesn’t mean that none of this is going to happen for ten years.

Q. The chapter on Edward Teller, the old Cold War atomic physicist, is fascinating. To me he is the quintessence of a certain kind of 20th century thinking: technology is mankind’s way of beating nature down, overcoming nature by sheer force of will. I mean, the guy wanted to use nukes to create a seaport in Alaska! In a sense, geoengineering strikes me as a descendent of that kind of thinking. There’s a different way of thinking about technology emerging today, which traces its roots more to biology than physics. Technology as smaller and more distributed, working with natural flows rather than against them, converging with nature rather than overcoming nature. I’ve always assumed that the arc of history will leave the 20th century vision of technology behind in favor of this new vision. But geoengineering makes me think that maybe the 20th century vision is going to win out in the end!

A. That speaks to the central theme of my book.

I want to say one thing first. The people I talked to who are the most thoughtful and interesting, a lot of them are physicists, and in the case of Ken Caldeira, actually worked with Teller at the Lawrence Livermore lab. He used to have lunch with Teller. A lot of these guys are really adamant about openness, transparency, the need for research that is not in the Department of Energy — not Edward Teller replaying itself. They are very conscious of the legacy of this kind of large-scale engineering.

This idea of smaller, more active management of our world is right; it is not necessarily true that geoengineering is not a part of that. My final chapter is a kind of parallel between geoengineering and gardening. This is about learning to garden the planet. I was inspired to think about this because of my wife’s garden, seeing this partnership with nature she has in her garden. It leads to a beautiful thing. The hopeful side of me thinks geoengineering doesn’t need to be a totalitarian, Edward Teller vision. It can be smaller, smarter. It can be modest, about regional stuff, experimenting, learning what works, what doesn’t work. Being humble about this, being open about this.

Q. But we’ve learned gardening over centuries. Shooting a bunch of particles up into the stratosphere seems ham-handed, like finding a dry spot in your garden and dumping a gallon jug of water on it. We just don’t know enough to do it elegantly yet.

A. The only reason there’s any urgency about this is there are potential catastrophes that await us if shit gets weird. If any of this stuff about dangerous climate change is anywhere accurate, we’re in for some very rough rides in the coming decades. How do we manage that risk?

But also, it doesn’t have to be shooting particles into the atmosphere in this massive, lets-control-the-universe kind of way. It can be: unless we do something in x number of years, Greenland’s gone and we’ve got 22 feet of sea level rise. Can we try to change the sunlight hitting Greenland and slow the melting somewhat? If it doesn’t work, reversibility is obviously hugely important. But it doesn’t need to be a totalitarian vision.

Q. The obvious looming danger is that rich people do this to save their asses and poor people get hung out to dry — which would be a continuation of what’s happening now, right? How do we go about trying to make sure that doesn’t happen?

A. That’s a really hard question. As you said, we haven’t done a very good job of that in anything we do — not only in climate. Millions of people starving to death and we don’t really care. Certainly there has been lots of progress, but generally, rich people take care of themselves. I don’t know how you change that equation.

It was interesting, when I was first starting this book, I went to a venture capital retreat and ended up sitting with this Wall Street guy. I was talking about exactly this, the problem of equity, worrying out loud about whether I should be writing this book. He had never heard of geoengineering, but I explained it to him briefly. He said, “Look, if we in the West have the ability to cool the climate a little bit, that would help people in the developing world. Don’t we have a moral obligation to find out if it could work?” It struck me. This stuff can be used for all kinds of purposes — it’s up to us as human beings to decide how we’re going to use it.

Q. What does your non-optimist side say?

A. There are a few things I worry about most. One is the fantasy of the quick fix. You already have people like Bjorn Lomborg talking openly about this. I’m sure we will see Heritage Foundation stuff coming out about the virtues of geoengineering. My immediate fear is that it will co-opt the political debate. That’s why it’s really important for scientists and journalists who understand that this is not a substitute for cutting emissions to get out in front. That’s my near-term fear.

Farther out is the idea that a nation or a group of nations will decide, for nationalistic or militaristic reasons, or a genuine belief that they can fix their problems, to do this. And it won’t be a nation like the United States or western Europe. It will be China, India, a collection of developing nations. It could be any group of nations. They will do it badly, and cause a lot of climate chaos, and it’s not clear where we will go from there. It’s a scary scenario. You can imagine this going forward with what look like good intentions, the same way Iran is supposedly going forward with nuclear just to power their country with clean energy, without any kind of vetting, safety guards, or transparency.

But as I wrote in the book, my nightmare scenario is that we won’t do anything. It will just be decades more of apathy. We’ll block progress on research on geoengineering, we won’t reform our energy system, we will just continue with the status quo for another two or three decades. We’ll just ride straight ahead into climate chaos.