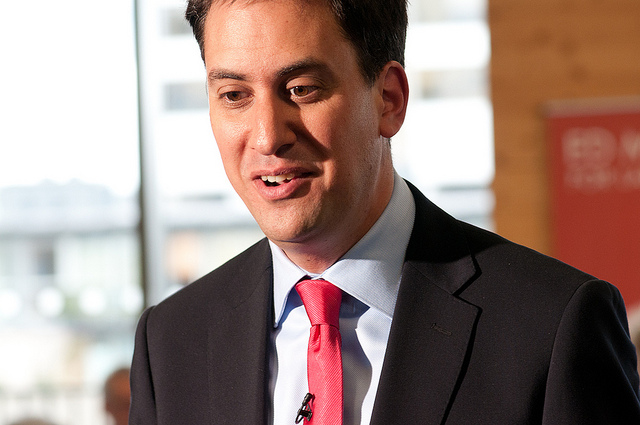

Ed Miliband, new leader of Britain’s Labor PartyPhoto: Ed Miliband campaignLONDON — The fraternal psychodrama playing out in the Miliband family may have passed you by, but over here it’s been the most interesting political soap since … well … Gordon and Tony.

Ed Miliband, new leader of Britain’s Labor PartyPhoto: Ed Miliband campaignLONDON — The fraternal psychodrama playing out in the Miliband family may have passed you by, but over here it’s been the most interesting political soap since … well … Gordon and Tony.

Previously on Miliband: Ed and David, sons of Marxist firebrand Ralph Miliband (a Jewish refugee from Nazi-occupied Belgium), enter politics. David, four years older, works in Prime Minister Tony Blair’s office, becomes a member of parliament, swiftly moves up the ranks and becomes environment secretary, then foreign secretary, and is widely tipped to become Blair’s successor and the new leader of the Labor Party. Ed, meanwhile, works in Gordon Brown’s office, becomes a member of parliament a few years after David, but rises equally swiftly, joining his brother in government as energy and climate change secretary.

When Brown steps down as leader, David declares his candidacy. Shortly afterward, Ed enters the fray. Seen as an outsider, and definitely the junior partner, Ed ultimately wins the race by the narrowest of margins. David sets off for the political wilderness.

With the drama coming to an end, attention is turning to what Ed Miliband would actually do were he elected prime minister in five years’ time. The labyrinthine electoral system by which the Labor Party chooses its leader would take pages to explain, but Ed Miliband won in the end by managing to amass more support from the trade unions than did his brother David. This means he is now dubbed ‘Red Ed’ by much of the right-wing media here, who predict a “lurch to the left” in the party. This is pretty dumb: The likelihood that anyone would lurch to the left and still hope to get elected is nil. Ed Miliband’s greater challenge may be to put much clear water between himself and the ruling coalition government on anything.

With the coalition government making much play of its green ambitions, it will be interesting to watch how Miliband will position Labor on the environment. As energy and climate change secretary, he won a lot of friends in the environmental movement. Writing in the Guardian, Friends of the Earth U.K. Executive Director Andy Atkins welcomed his appointment, giving Ed much of the credit for bringing the Climate Change Act (which commits the U.K. to binding targets on CO2 emissions reductions) into force. It was also Ed who introduced the feed-in tariffs that will reward households that install renewable energy technologies, and insisted that no new coal-fired power plants could be built without carbon capture and storage technology. Even stern critic George Monbiot reckons Ed is the only major party leader who recognizes the contradiction in having greenhouse-gas emissions targets and hunting for new oil.

Will this track record be carried into practice, and will Miliband be able to hold the coalition government to account if it backtracks on its commitments? With the Labor Party conference in full flow in Manchester as I write, it’s astonishing to learn there is not a single major session on the environment. Yesterday’s events were dominated by Ed’s first speech as party leader, the central theme of which was “a new generation for change” — an attempt to put clear water between the Ed generation (he’s 40) and the Tony/Gordon generation. So, no more “New” Labor; the Iraq War was a mistake; and the party has become stuck in its old certainties. And though there wasn’t much focus on the environment in the speech, a short passage proposed climate change as another feature of the generation gap. As he put it: “When I think about my son, I think what he will be asking me in 20 years time is whether I was part of the last generation not to get climate change or the first generation to get it. And climate change … can’t be tackled by the politics we have.”

Well, it’s very early days for Ed, and much to do if he is to have any chance of beating Prime Minister David Cameron’s coalition in a few years’ time. If his older sibling does indeed leave politics today, it should at least avoid an even worse struggle for power than we saw in the Blair/Brown years, and give Ed a clear run. How much he’ll want to make the environment a key platform of his leadership remains to be seen.

Commentators in both the Daily Mail and The Daily Telegraph recently launched spiteful attacks on him for allowing the Copenhagen climate summit to influence his marriage plans, knowing that much of their readership is still ready to see the environment as the concern of nutters and do-gooders. Many of these readers are part of the group of 5 million voters that Labor lost between its landslide victory in 1997 and its election loss in May of this year.

If Ed wants Labor to reshape the center ground of politics, as he claimed in his speech, he will have to find ways to sell environmentalism to them. His best route in may be in his comments about “community, belonging, and solidarity.” Reframing a protected environment as the necessary backdrop to these laudable qualities might give him more traction with Middle England than any number of visits to international conferences.