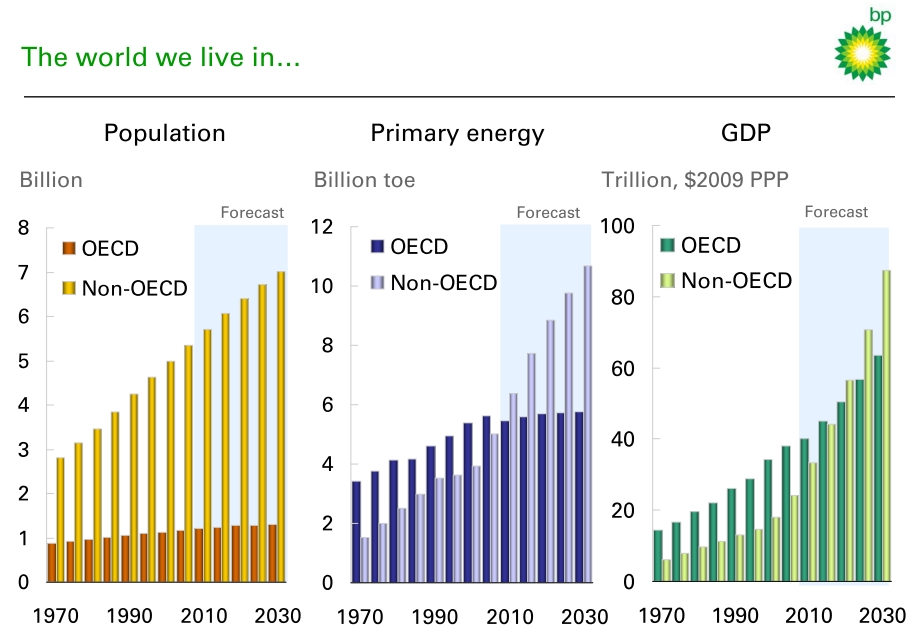

It is taken for granted by just about everyone that the developing world is going to grow like gangbusters over the next few decades. Population will grow, GDP will grow, and consumption of energy and other resources will grow. Look at this, from the BP Energy Outlook 2030:

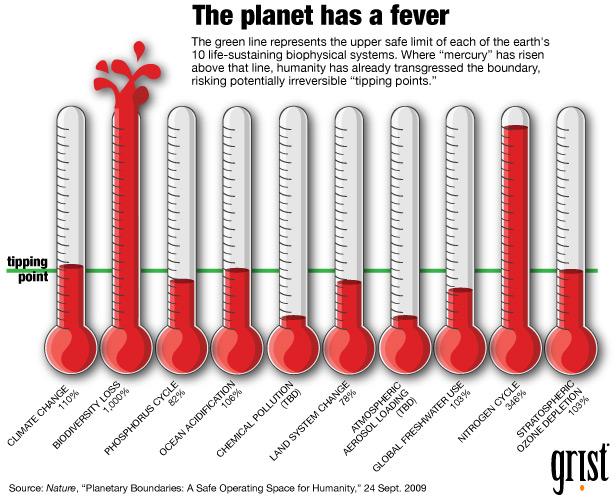

This expectation — nay, this certainty — shapes all our forecasts, fears, and plans for the coming century. Just as certainly, we are approaching several biophysical thresholds:

Yikes! A collision of humanity and ecology seems inevitable. It’s no wonder there’s such a fervent desire for a “miracle” energy technology breakthrough. It seems only a deus ex machina can get us out of this pickle.

But what if the developing world didn’t need to grow quite this much, quite this fast? What if social and political change — changes in government policy, economics, cultural norms, etc. — can do for demand what technological change can do for supply?

One has to be careful here. Obviously the people of the developing world deserve a decent standard of living just as much as anyone in OECD countries. But we’re too quick to equate GDP, a measure of economic activity, with quality of life. Improving life for the people of the developing world need not look like the kind of GDP growth on the chart at the top.

Which brings us to my new hero: Niu Wenyuan, adviser to the Chinese state council, chief scientist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and director of the Chinese Ecological Economics Society.

Eight years ago, Niu tried to introduce a “green GDP,” but it never took off. In China, provincial leaders have long been rewarded for GDP growth and they’re terrified that a new system of measurement would undo their gains.

But Niu is back to try again, with at “GDP quality index.” Quoting an excellent piece from Jonathan Watts:

Niu’s formulation combines five elements: Economic quality, which considers the amount of resources and energy needed to generate each 10,000 yuan of GDP; social quality, which includes differences of incomes between rich and poor that might led to destructive riots; environmental quality, which assesses the amount of waste and carbon generated per 10,000 yuan of economic activity; quality of life, which figures in life expectancy and other human development indicators; and management quality, which measures the proportion of tax revenue used for public security, the durability of infrastructure and the proportion of public officials in the overall population.

Niu stresses that unlike green GDP, the GDP quality index uses data the government already collects, so it’s much easier to understand, calculate, and administer. He plans to release it annually, refining it as he goes.

There are efforts not that different from Niu’s going on the U.K. and France (and Bhutan) — I wrote about them a little bit here. But it strikes me as significant that Niu’s effort is native to China. The country needs to forge a new model of development or all is lost.

How much can quality of life and GDP be pried apart? Who knows. Efforts to do so seem fitful and slow so far, a long way from actually changing government policies. Rethinking how society measures value is a difficult thing. Nevertheless, it’s crucial, and we shouldn’t give up on it.

More broadly, we should not give up on social and political change. People tend to be very cynical about it, especially those who have endured prolonged exposure to contemporary U.S. politics. This is understandable; technological change seems to come constantly, quite visibly to the naked eye, as it were, whereas social change can often take the form of what Jay Gould called punctuated equilibrium: Things can move only slowly and incrementally, or not at all, for a long time — and then, whammy. Every sudden lurch in social or political life is preceded by a long period of what seems like futile struggle. Change is unpredictable, even by those working on it every day.

Nonetheless! We still ought to be boring those hard boards, as Weber would say.