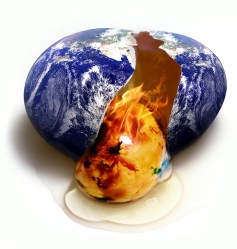

Image by Mark Rain.

It was 1972, and to anyone who was paying attention, it was obvious that we humans were making a real mess of things. Tropical forests were falling at an alarming rate. Whale populations were in a death spiral. Our cities were choked with smog, our rivers had turned into fire traps, and we were getting the first inklings that all of our industrial activity might actually be warming the globe.

To right the course, representatives from 114 countries met in Stockholm, Sweden, at the U.N. Conference on the Human Environment — the first major global effort to clean up our collective act — and an era of environmental diplomacy was born.

Four decades later, what do we have to show for it?

First, the bad news:

Fails

- Biodiversity: The fight to save the whales back in the 1970s and ’80s seems like a quaint notion now. Around the world, 20,000 species of plants and animals are at high risk of going extinct in the wild, according to the Union for Conservation of Nature, which maintains the “red list” of species on the brink. If we continue the way we’re going, we could lose three out of every four species on Earth — the largest mass extinction since the one that wiped out the dinosaurs 65 million years ago. (The New York Times has a nifty, if totally depressing, infographic illustrating all this.)

- Oceans: Lest you think all those critters have no impact on your life, consider the ones that live in the oceans — the ones that are super tasty slathered in butter and herbs, with a squeeze of lemon. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration reported earlier this year [PDF] that, with tough catch restrictions, six fish species returned to healthy levels in U.S. waters this year. These are the exceptions to the rule, however. Eighty percent of the world’s fisheries are either fully exploited or in decline. Meanwhile, coral reefs continue to bleach and die (thanks, in part, to your sunscreen, but mainly because the oceans are getting warmer) and ocean acidification threatens to throw the whole marine ecosystem into turmoil.

Okay, the good news? Honestly, there’s precious little of it.

Wins

- Forests: Worldwide, forest destruction has slowed over the past decade. In the Amazon, deforestation has dropped to its lowest levels since 1988, according to a report released earlier this month by the Brazilian government. This news came the same week that Brazil’s president, Dilma Rouseff, was slammed by conservation groups for pardoning loggers who have illegally cleared forests, however. And worldwide, trees continue to fall at an alarming rate. In the last decade, we’ve lost forests equivalent to the size of Germany.

- Ozone depletion: The Montreal Protocol, written up in 1987 and signed by 197 countries and the European Union, heralded the phaseout of chlorofluorocarbons (chemicals once commonly used in spray cans) and other “ozone depleting chemicals” that were eating a hole in the atmosphere. If all goes as planned, the ozone will be patched up by 2050. But again, the news is not all positive. Human-made chemicals continue to cause concern among scientists, and 2006 saw the largest Antarctic ozone hole on record. We’re apparently not out of the woods yet.

- Leaded gasoline: This is the single unmitigated success that I could come up with. The Partnership for Clean Fuels and Vehicles, launched in 2002 at the Earth Summit in Johannesburg, has helped more than 100 countries phase out leaded gasoline. Today, all but six countries have banned the stuff. (Afghanistan, Myanmar, and North Korea are the only countries that are still running solely on leaded gas — the other three offer unleaded, too.) The phaseout saves a jaw-dropping $2.4 trillion a year, according to a recent study [PDF] in the Journal of Environmental Health that measured the benefits of increased health and IQ, and reduced criminal activity that comes with decreased levels of lead in the blood.

If there’s a caveat here, it is this: The phaseout of leaded gasoline isn’t the result of some grand multinational treaty. Its roots lie in an informal network of non-governmental organizations, governments, and corporations that worked country to country, below the international radar. The Partnership in Clean Fuels grew out of that more grassroots effort — and now 99 percent of gas supplies on the planet are lead-free. So more than a demonstration of the power of international cooperation, it is a lesson in the power of working from the ground up, and perhaps a guide for future efforts.

Next: Can the Earth Summit be saved?

Read all of Grist’s coverage of the Earth Summit here.